Should influencers get political??

What is the old aphorism?

“The three things you should never discuss in polite company: politics, religion, and money.”

I can’t say whether my parents considered family to be “polite company,” but we regularly discussed 2 out of 3 of these in our house: politics and religion. Money is not something we openly talked about, probably because my parents never really had enough of it to make it a worthwhile topic of conversation. But, my family was very religious and therefore, cracking open the Bible to dissect a verse or two was as non-controversial as serving up a plate of roasted peanuts to our guests.

Also, my father has been political for as long as I can remember and thus politics was a frequent subject of discussion (though, not usually at the dinner table–those were rather quiet affairs, which you already know if you’ve read my book). After dinner, while Omma was piling dirty dishes into the sink, Daddy would often sit back and query the table with some provocative question that was, if not overtly political, one that could easily become political. And though Daddy spent quite a bit of time in front of the TV, sparring with pundits, journalists, and politicians alike from the safety of his cracked black leather recliner, he also relished the opportunity to try his hand against “live” opponents, typically at the small soirees my mother would host from time to time or even at prayer group meetings.

Why, just the other day at the breakfast table, after finishing off the avocado toast I’d made for him, he piped up out of nowhere with: “Donald Trump is so STOOPIT!” (Daddy’s been quite unhappy with how the tariffs have affected his retirement portfolio, among other things). A few weeks before that, when I was visiting my parents in Chicago, Daddy lumbered up the steps from his man-cave (the family room) to slide into a seat at the dining table where we had all congregated after dinner and interrupted everyone to pose, “So what do you think about AI?” And thus ensued a lively debate about the pros and cons of artificial intelligence, which ended with me regaling the family with a blow-by-blow of one of our favorite movies of all time: Terminator 2.

Perhaps because of my father, I’ve never been uncomfortable talking about politics, even when I probably should have been. In 5th grade, I bragged to all my friends that my parents were, of course, voting for George Bush (Sr.) because I thought he looked “more presidential” than the other guy, without realizing that my parents were, in fact, proudly voting for the decidedly blue candidate, Michael Dukakis. I had all the confidence of someone used to a world filled with “political things,” despite possessing very little knowledge about those political things.

Eventually, though, my knowledge caught up to my bluster, especially after law school. Not because law school taught me everything I needed to know about American politics, but because law school taught me how to think about important questions, any important question, including those that would inform U.S. policy. The most valuable lesson I learned was this:

Listen first, ask next, answer last. WAY last.

The Socratic method is famous for humiliating those who would shoot from the hip and my professors were skilled at disarming the trigger happy among us. I soon discovered that the best way to avoid sounding like an idiot was to avoid saying anything until you were pretty darn certain that your position was, if not bulletproof, very defendable. As law students, we became well-versed at itemizing the “relevant facts” inside the cases in our textbooks (usually, there are about 5 to 10 of them–relevant facts, that is) to which we would then apply the law. The process was simple, even elegant, like fitting a clear glass dome over a plate of cookies on a cake stand. But grey areas abound even in such artificially contained hypotheticals, and it was within those shaded corners that Professors Currie, Sykes, and Epstein picked us apart with the same relish I harbor for a plate of cookies.

It should be noted, however, that these “fact finding” drills were also misleading–they made us believe that our days as lawyers would be limited to identifying 5 or 6 “key facts” and then applying the statute buried inside a dusty legal primer to these easily discernible items. But, when, in life, are the relevant facts limited to just a handful? When is the applicable law as clear as the glass housing a batch of freshly baked cookies (ok, I spent the past week recipe testing cookies, got it?)? Arriving at the logical conclusion in a broken staircase lawsuit under Illinois construction law is a fairly discrete exercise compared to, say, establishing the scope of the 4th, 5th, and 14th Amendment vis-a-vis immigration law. But the stakes are high–the staircase lawsuit will impact a few people, entail the exchange of roughly $20,000 (I would know–I litigated this case), while the larger legal questions will have an immediate impact upon millions of people across our country.

Last week, I was invited to moderate a book chat with Gaz Oakley, who is touring his most recent book, Plant to Plate (which is beautiful, btw). The event was held at my favorite bookstore in Los Angeles, NowServingLA. NowServing is located in the heart of LA’s Chinatown. On my way there, I was met with blockades erected by the LAPD, throngs of protesters with their signs, helicopters hovering above our cars to monitor the historic deployment of military forces against U.S. citizens without cooperation from the sitting governor, something that hasn’t occurred on U.S. soil since 1965, when President Johnson deployed the guard to, ironically, protect protesters (you don’t need to read between the lines to see where I fall on this issue).

The ICE raids, the protests, the military were all right there, within arm’s reach. During our chat, we had to pause our conversation several times to allow for the sirens to fade, the police cars speeding through Chinatown to pass, the unholy noise from the squealing tires jarringly at odds with Gaz’s description of his garden in Wales. Later that night, I wondered whether it made sense to share photos from the event or from the protests on social media. Should I share both? No, surely I couldn’t share both, as doing so would be obscenely tone-deaf. In the end, I chose to share neither.

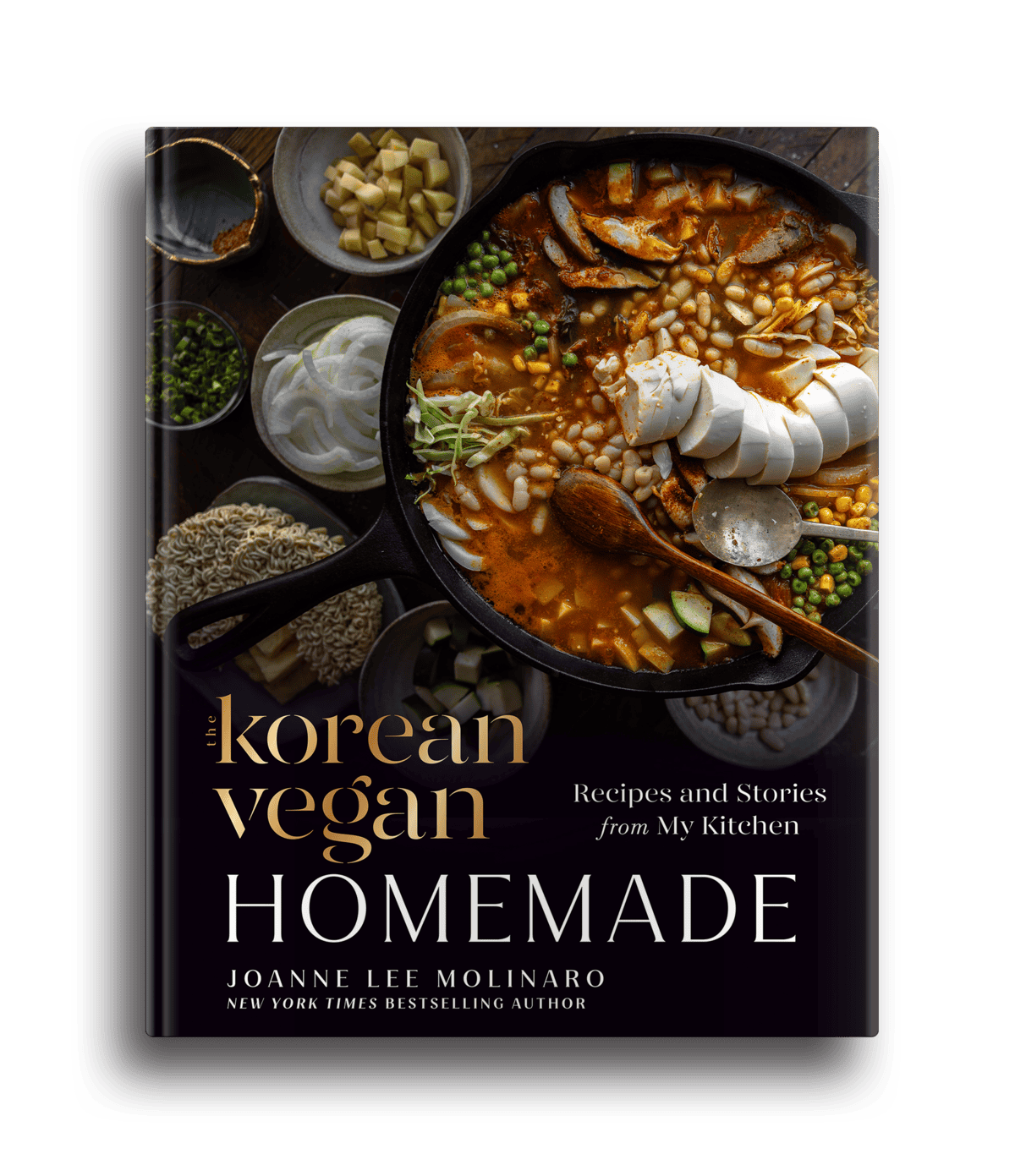

Over the past several weeks, I’ve been agonizing over this question (and, sadly, some of you have been party to my agony, sorry): what am I supposed to post about on social media? With a book coming out in just a few months, the answer should be obvious: recipe videos about your amazing, awesome, forthcoming book (I might as well have copy/pasted this from my publisher’s most recent email to me)! But, I wake up each morning, read the news, see the headlines, scroll through my Threads feed, and the idea of editing a video on how to make rice bread or chocolate chip cookies feels, in a word, impossible.

Not only might it come across as insensitive, it literally feels impossible, like I’m stuck inside a tarpit, immobilized at a time when I’m required to be most mobile. But even if I decide to post something that isn’t “just a recipe,” and, instead, say something “political,” what can I say? What should I say? Indeed, should I say anything at all?

There are some who think I should not:

“I love your content, but I feel like I never get to see anything happy it’s always some kind of sad rant.” This was a comment I received on a video I made several days ago about the time someone told me to “go back to Korea,” which inspired a larger discussion on how I felt about Trump’s manhandling of immigrants. Several people agreed with this sentiment (as evidenced by 148 likes), one even calling me a total “wet blanket” for sharing my views on a topic that is both personal and political (this person was blocked). The policing of political speech, of course, isn’t new. Casting my video as “some kind of sad rant” and implying that my job is to entertain folks with only “happy” videos is, of course, unintelligently reductive and maddeningly dehumanizing, but it is, sadly, an effective tactic.

Content creators and influencers are beholden to thoughtless and, quite frankly, not-very-smart users who are as prone to “swipe away” as they are to leaving micro-aggressively racist drivel like the above. Those who derive a living, even indirectly, from posting videos on social media are literally risking their livelihood by sharing political takes that will piss off viewers and, more importantly, scare off potential brand partners (in some cases, be in breach of contract with existing brand partners). But these days, the stakes are even higher, right? Anyone who speaks out against Donald Trump is now putting themselves and their families at risk. Twitch star Hasan Piker, a U.S. CITIZEN, was detained for two hours when he tried to re-enter the United States so that border patrol agents could interrogate him regarding his criticism of Donald Trump and accuse him of being tied to terrorists.

So, am I the idiot for putting a target on my back? For driving away brand partners? For failing to court offensively clueless Instagram users who might buy my book if I just shut up and dance for them?

For some, the answer is a very loud “NO!” In fact, thousands and thousands of people (many of you included) have written to tell me how grateful they are that I continue to share my legal knowledge and thoughts on political topics. However, the truth is, I post these things not just because I want to help people feel seen or provide useful information or get folks to think a little bit more, but because it’s starting to get so scary, these days. My videos, my rants, my dissection of SCOTUS rulings–they’re like SOS’s: “is anyone else out there?” “does anyone else see what I’m seeing?” “is anyone else afraid, too?” Those who would silence us have weaponized the “casual comment” (“I wish you wouldn’t post such sad content all the time ☹️”), gaslighting us into thinking “maybe it’s not as bad as I think?” And thus, I hit the “publish” button hoping that others will prove that I am as sane as they are (or, at least ascribe to the same version of sanity).

I’ve heard a lot of influencers, content creators, and celebrities speaking out about so many political issues over the past few years and, for the most part, I admire them for it. I am grateful to them for it. Because they make me feel less alone.

But, what about those who believe that anyone not saying something should be penalized, taken to task for being a coward, “canceled” for caving to the demands of capitalism instead of speaking out “for the people!”? For the past few days, my TikTok feed has been inundated with smaller Asian American influencers who are “outraged” that so few of their peers are “saying anything” about “what’s happening in L.A. right now” (as if Asian Americans are only obligated to “say something” when the atrocities reach a certain geographic proximity) because they’re too afraid of losing out on “brand deals.” I’ve seen other food influencers who have been pressuring their peers to speak out on Palestine and Gaza, suggesting that those who don’t no longer merit your respect.

To be honest, I find this outrage to be nearly as stupid (or, if I’m feeling charitable, “misguided”) as the person telling me to “shut up and dance.” I mean, is it really that hard to compute that those who are most at risk of being detained, deported, and disappeared are the families of the very people they are calling out? The Trump Administration has made no bones about discarding due process in favor of expediency, trampling on First Amendment rights to meet a deportation quota. The Administration has indicated that it intends to utilize AI to crawl through people’s social media accounts to determine whether visas and status should be revoked for saying the wrong things. Perhaps the reason for their silence isn’t as pedantically commercial as missed brand deals but the fact they are scared their undocumented elderly parents, aunties and uncles will be deported should they bring undue attention to themselves. The truth is, it shouldn’t be that hard to arrive at this conclusion, but perhaps these “activists” are hampered by something far more mundane than their rage.

Does everyone remember the “black box” incident? For those who don’t immediately know what I’m talking about, I’m referring to that day on social media where everyone posted a black box on their Instagram feed to show solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. I will readily admit that I very performatively posted a black box, right along with everyone else, and I say that it was performative because I posted it while hardly understanding what it was meant to signify. I’d just gotten out of the shower and was scrolling through my social media feeds in the hour before it was time to start billing (I was still working at the Firm). I saw everyone posting black boxes and urging everyone else to post black boxes and it seemed as though it vaguely had something to do with amplifying the voices of Black American creators and so before I received too many more DMs and comments “encouraging” me to do the same, I posted my black box, changed into my “at home lawyer outfit,” logged onto my work laptop, and lawyered for the rest of the day.

Look, I think the intention behind the idea was a good one, but it goes to show that good intensions are not dispositive of good results. The “black box” grew to be performative almost instantly because, surprise, surprise, when you operate in an attention economy, mercenaries will use whatever tools they’re given to shield themselves at the lowest cost. “Are you saying all I have to do is post a black box for one day and the world will think I’m not racist? Deal!” No introspection required. No research necessary. What a convenient cloak that black box was for many who were otherwise unwilling to interrogate their own anti-Blackness. But more importantly, influencers and content creators were now quickly discovering what politicians have known all along: how easy it is to grow “famous” for one’s activism. What was designed to amplify Black American voices was hijacked by non-Black creators who dubbed themselves “activists” with such dizzying alacrity, it was hard not to throw up.

I learned by watching that my place was really to say nothing and listen. I am not Black and thus, I have not experienced anti-Blackness. To the extent my posting of that black box signified to Black Americans that I saw their pain and rage, I’m glad; but, I worry that the demonstration was ultimately diluted beyond recognition by those crude proxies endemic to social media. Because how on earth could we have truly believed that something as silly as a black box on an Instagram grid could encapsulate the debt humanity has incurred to the Black community?

Since then, I have concluded that I will never be coerced into posting political speech again. I will post what I will post.

But what’s wrong with activists becoming famous? Even making money off their activism? I mean, activists need to eat, too. They have rent, too. And won’t their celebrity inure to their causes? Isn’t it a win-win? You know where this is headed: don’t bite the hand that feeds you (and your ego). What is the difference, really, between the person who chooses not to post certain political speech because they’re afraid of losing followers and brand deals and the person who does post certain political speech to gain followers and clout? I’d guess not a lot. Both are subject to the volatility of popular opinion and money. But often times, those in the latter category of “activists” are too young or inexperienced to have drawn the lines they’re willing or unwilling to cross. Indeed, many of them become so addicted to the views, the comments, the virality of their activism, they can no longer describe the shape and form of their integrity. I say this as someone who has experienced this addiction firsthand.

Contrast this to my friend, Rebecca. I’ve known Rebecca since I went vegan in 2016. She was one of the early members of the “New York City Vegan Supper Club,” the informal group that my friends and I started back in those early days, when all of them (and not I) lived in New York. Rebecca is a Palestinian American vegan influencer, and since the crisis erupted in Gaza, she has done more than any single human being I personally know to assist, physically and financially, with the placement of refugees from that region of the world. She is currently moving to Cairo, so she can devote all her time to this effort. But amazingly, the overwhelming majority of her content has nothing to do with this conflict. Rather, she continues to share videos about vegan restaurants she discovers on her travels. While other “pro-Palestine” influencers have made thousands and thousands of dollars for themselves with each viral video (they get paid per view), Rebecca lives quite humbly and spends much of her free time fundraising or literally helping displaced people find a new home. She does not profit off her advocacy. Having talked to her on numerous occasions about her work, I can say with absolute certainty that I have the deepest respect for her form of activism because it is so profoundly selfless.

I’m not saying that all activists need to be like Rebecca (though I daresay the world could use more people like her). But I do think content creators and influencers should be careful before they wade into the world of politics, particularly when they intend to use their platform to amplify someone else’s story. I started The Korean Vegan, in part, as an act of resistance to Donald Trump’s first administration. I share stories that are personal to me with the hope of inspiring empathy, compassion, and, let’s face it–critical thinking. I believe these are the pillars to a strong democracy, but I couch these discussions in the stories over which I have absolute authority–my own. There is no one on the planet who can unseat me as the author of my stories, and as such, I come to the table with credibility, one of the most important tools of any advocate. But part of it, too, is because I want to feel seen. I had long discussions with my therapist about this issue–am I allowed to want to be seen in my work? The answer, she persuaded me, is yes, yes of course you’re allowed to feel seen by your work.

Since then, I’ve spent the last several years wrestling with the role my ego is permitted to play in this project, precisely because I never want to inadvertently sell the content of my speech to the highest bidder. Who do I become when the words I publish are so heavily influenced by the likes, comments, and shares of the nameless masses that are now savvy enough to know their power over me? Who do I become when my silence is purchased by those who wish to maintain their power? And what happens to those who require our advocacy? Those who seek justice? Will their stories be tarnished by the bleak levers of the “creator economy”? What happens to them when they are left behind for a newer, shinier beneficiary of an influencer’s platform? And will those who might have otherwise listened be turned off by the performative tears of yet another influencer activist?

The barrier to entry to these discussions is lower than it ever has been. The gatekeepers to what counts as “value” appeal to the basest of instincts. That is the attention economy. And I wonder whether we truly should be urging everyone to speak up and speak loud, when really, they could afford to first sit down to a post-dinner conversation with my Dad.

Recent Newsletters

Not Subscribed? Join Us Here.

Parting Thoughts

The nice thing about social media (for all its flaws) is that it connects people who might not otherwise be connected and, for better or worse, it disarms us into being more vulnerable. You may not be brave enough to say “Yeah, I’m scared for our country” at an actual dinner party (it could cause a bit of an awkward pause…), but maybe you’ll express a similar sentiment when commenting on one of my videos. At work, it might be strange to admit that you hate everything that’s currently happening in the world, but perhaps you DM me after reading something that I posted on Threads that resonated with you. If you’re like me, you won’t share your deepest, darkest fears with the people you know in real life, but you’ll share them with a bunch of strangers who read your emails every week, because doing so has now become an act of defiance, an outrageous investment in compassion, an unflagging belief that together, we can form the scaffolding for the moral arc we committed to uphold.

Resources and How to Help:

National Immigration Law Center

Central American Resource Center of Los Angeles

New York Legal Assistance Group

Wishing you all the best,

-Joanne

Joanne, please don’t change what you want to talk about to appease anyone. Your content is always insightful, well explained, and so often really resonates with me whether its about politics, your parents, weight, or about your fur babies. Don’t let the Trolls get you down. They are just unhappy in their own life and are free to unsubscribe.

Politically, these are not normal times and IMO the time to stay silent is no more. Horrific things are happening to innocent people and we can’t just standby and hope it will all work out. The recent No Kings rallys showed the world that we aren’t going to stand for this.

I think the personal IS political. Your choice ( and mine) to be vegan is a personal but also a political choice. The food we buy and eat supports those that produce it and prepare it. To think otherwise is to be naive. Now, like religion politics does not need to become a badge or something to be used as a weapon. Like your friend Rebecca actions often a clearer indicators of a person’s politics than social media pronouncements.

Andrea, I agree. Our choices are often sourced in politics, whether we realize it or not. I could NOT agree more, though, with what you say at the end: actions are a clearer indicator of a person’s politics than social media pronouncements. What is they say about character? It’s how you act when nobody’s watching!! Thanks again for weighing in!! <3

There is so much misinformation out there that I think it’s great to hear personal, first-hand stories. My views align with yours (raised by liberal Kennedy campaigners who taught us to think for ourselves), and I’ve found no truer pulse than listening to what people, not the news media (or entertainment posing as news media), have to say.

With that said, I’ve heard many individuals from the conservative side of the aisle spouting hate, bigotry, and misogyny, so I appreciate all communication about personal experiences, liberal or conservative, so long as it’s respectful. I say share away, and if people can’t understand your very human, very common American experience, then they don’t have to read it. You offer the option to only receive recipe emails, which is thoughtful.

Thanks Kris. I think you’re so right–personal experiences often ground us in a way that the new’s doesn’t. It reminds us that we are all human, after all, and hopefully, keeps us accountable to what that means, right? And I’m glad you noticed the “recipes only” option! I know my emails can get “heavy” and I also do not judge those who want to keep it light, when so much of the world IS heavy. Thanks so much for weighing in, Kris!!

Joanne, I gratefully applaud you for your courage in so clearly outlining the dilemma you face. It’s a well-reasoned and compassionate look at the problem, far from performative tears or lecturing.

I’m not an influencer, but our daughter is, at a much lower level than you, but still, she makes her living on Instagram. She lives abroad, in a nation not facing the loss of a long-cherished democracy, so has not, as a woman, been robbed of bodily autonomy by far-right forces. I’m glad she’s safe. Still, with a much smaller audience than you, she most definitely can’t express her political views: it’s literally her bread and butter, her rent and clothing, and she can’t afford to lose followers.

But I know that if she could, she’d be as honest as you are here about the unprecedented dangers our country faces. As a older privileged white woman I’m as “protected” as I can be and can and should speak out about injustice and greed; you have skin in the game and I admire the bravery you demonstrate in this essay.

I don’t think you should coddle those readers who are here for the food and only the food and can’t be disturbed by political reality. Surely, adults capable of following sometimes complex recipes are also able to absorb an intelligent woman’s beliefs in a time of national crisis without fluffing off in a huff.

As for me, I’m off to make those delicious-sounding garlic rolls!! And as soon as possible, off to the next No Kings march.

Mo, this is the mom energy I am so grateful to receive from women like you!!!! Like RAWR!!! I love how thoughtful you are when it comes to parsing what’s similar and dissimilar in our relative circumstances, as well as between me and your daughter. When I was first starting out, with less than 10k followers, I was pretty open about my politics, but guess what? I had a full-time lawyer salary paying my bills! Since doing this thing full time, I’m so much better aware of what a precarious position it is that your daughter occupies. I hope that, with time, she can cultivate a following much like my own–one that, for the most part, appreciates a fuller picture of who I am and my values.

As for those “fluffing off in a huff” (man, definitely using that again in the future!!), if they do, they hopefully do so without much ado. But lucky for me (as you’ll see in the comments here), even those who don’t see eye-to-eye with me remain respectful, kind, and generous in their honesty. I’m lucky for that, but I imagine that has something to do with the fact that my readers here tend to be a bit more mature than those squawking on social media!! LOLOL!

I hope you enjoy the rolls. My brother said it was like the best bread he’d ever eaten in his life when I made them for Thanksgiving!!! And his son, my nephew, ate like 3 of them for his entire Thanksgiving dinner!! <3

I think if you want to speak up you should and if you don’t then don’t speak up. Also, don’t judge people either way. Yes, I think DJT it STOOPIT.

Mary, you are a gem. ALWAYS!!! Thank you for your support and the vote in confidence!!! <3

I believe in free speech and I believe everyone is entitled to their opinion. With that said, I also believe that an influencer should be “gentle” and not push their opinion too hard on the wrong channel. From what I’ve seen so far from your writtings, I am pretty sure that our political opinions would clash, but I love your cooking, your recipes, and your family stories. I’m sure you have other followers that fit my description, and I’m sure you wouldn’t want to scare them away.

The lady who commented before me, Cindy Dancer, is right. If you like to get political, maybe you should have a separate channel.

Hey Larissa—thank you for your honesty. No matter why you’re here, even if we don’t see eye to eye on everything, if you enjoy the stories about my family, I have to believe we have enough in common to make the conversation worthwhile. I am grateful for that and for you!

Thank you for long-form content about what is happening and your experience in this crazy online space. I dip my toe in occasionally but have to really think about what I’m putting out there and the intention behind it. I appreciate people who understand nuance and that life and our experiences cannot be put into the dualistic terms. The food you create, the multi-faceted human being you are and your experiences shouldn’t have to be separated. I have compartmentalized myself according to different groups I’m a part of to feel safe. Sometimes that brings sadness because I end up wondering who really knows me. I appreciate people like you Joanne who can show up with as much of of who they are and be authentic with others. Keep shining a bright light on things. Made kimchi last week and thought of you!

Cristina, as you astutely note, life is not black and white and those who choose to portray it as such commit a sort of violence on everyone else. How we show up in this space is rife with subtleties and at bottom, I feel the answers must always begin and end with compassion. I’m so glad you made kimchi. It makes everything better. 💕

I believe in freedom of speech and you could have two separate columns so that those who do not want to read about what’s happening but want to see your recipes can do so. We all have a choice. I’m alarmed at what Trump is doing and hearing from people who are in the thick of his immigration policies is important. It helps us distinguish what’s real and what isn’t.

I love this Cindy. “We all have a choice” is a great way of putting it. And thank you so much for the small note of solidarity. 👊💕