My Mother’s Birthday, A Zucchini Tart, and Hurdling the Language Barrier.

The Podcast is Back!

Listen to this week’s newsletter below, on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your podcasts!

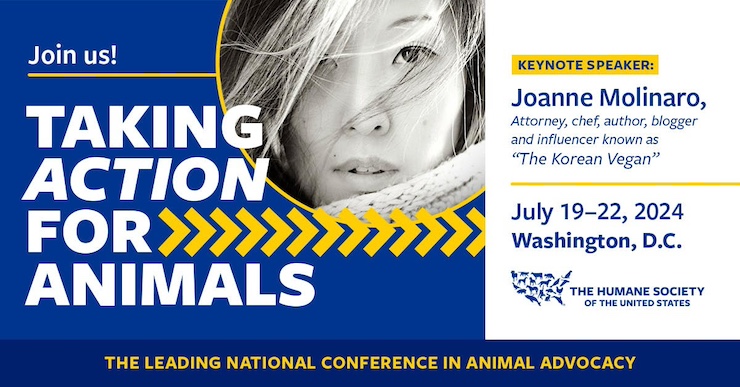

On Saturday, July 20, I’ll be sharing stories and signing books in Washington D.C. at the Humane Society’s annual conference. If you’re in the area, come join us!

Use my discount code: JMTF24 to save $20 on registration.

Every Puzzle Has a Solution.

I’m writing this newsletter the morning after the assassination attempt on former President Donald Trump. This is not an overtly political newsletter, but, I confess, I find it hard to think about much else at the moment.

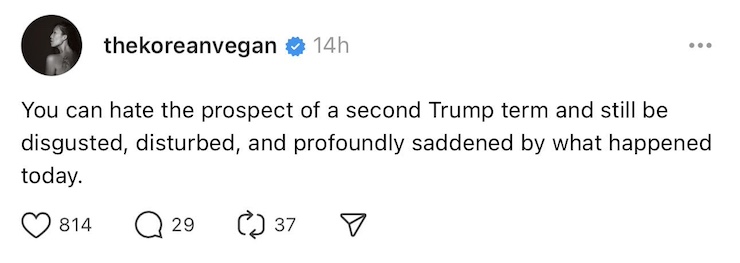

Last night, I posted the following on my Threads:

Surprisingly, there were commenters who seemed irritated, even angry that I expressed any sort of anguish over what occurred. I was accused of not taking seriously enough the danger Trump poses to our democracy and some even expressed open disappointment at the shooter’s poor aim.

It disturbs me that I have to remind people: two human beings died due to gun violence at this rally. That political violence is neither new nor rare in the past decade. That it isn’t unpatriotic, fascist, or “wrong” to be sad about this, regardless of the political beliefs held by the perpetrators or victims.

I’d originally intended this week’s missive to include a short story about my mother, who just celebrated her 75th birthday. I wanted to celebrate her and what her stories have meant to me and, by extension, to all of you. I feel, though, it would be strange and perhaps a bit tone deaf to not at least acknowledge that many of you might be feeling a little shell-shocked, too, by what we all witnessed on TV this past weekend.

Thus, if I may, friend, just a short detour before getting to the story of my mother to tell you a slightly different story, the one about why I started sharing stories at all on what was ostensibly supposed to be a vegan food blog:

I started The Korean Vegan back in 2016. Many of you are familiar with the origin story of TKV–how my then boyfriend (now husband) Anthony adopted a plant-based diet for health reasons and persuaded me to join him. I was largely in charge of providing our meals–though I wasn’t a very experienced cook at the time, I had far more hours of the Food Network under my belt than he did. As such, I started experimenting with vegan cheeses on our pizza, beets and black beans for our burgers, and even a decadent eggless and dairy-free chocolate cake.

Shortly after I jumped on the vegan bandwagon (mostly as an experiment), Anthony deployed flattery as part of his campaign to keep me from turning back:

“Your food is so good, you’re more vegan than I am now. You’re the Korean vegan. You should start a YouTube channel called ‘The Korean Vegan’ sharing all your recipes.'”

That was in February 2016. Later that year, Donald Trump was elected President of the United States and I discovered that I did not know my country–my country–as well as I thought I did. In fact, I started to wonder whether “my country” would even agree that someone who looked like me belonged inside its borders at all.

The turmoil at feeling “rejected” by America was soon eclipsed by fear for a country I still loved. America paved the way to democracy in my father’s country. America opened its doors to my mother, who then brought her family to the glittering teeth of Lake Michigan. America gave me Sesame Street and my best friend Reena and the rough bark of the crabapple tree I liked to rest my face against in summer.

But America seemed poised to lose its soul, torn apart by a feral tribalism, a quivering polarization that seemed to have emerged, overnight.

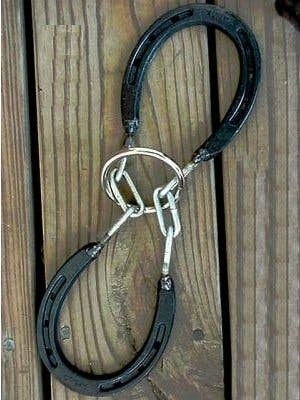

Perhaps driven by anxiety, I chose to view this schism in our country as a puzzle. In sixth grade, my homeroom teacher, Mr. Gerbarian, would bring into the classroom a pair of cast iron horseshoes held together by a few inches of chain. A small, seamless ring–about 2-inches in diameter–encircled the chain linking the two horseshoes. And everyday, he would put a blindfold on, pick up the horseshoes, and, in a few seconds, by some miracle, detach the small ring from the two, large U-shaped hunks of iron–which were still bound together.

“This is a puzzle,” he’d say, while loosening the blindfold. “If I can do it, so can you.”

He’d then invite the entire class up to examine the horseshoes, the steel ring. I let my fingers glide across the black surface, feeling for a catch, some hidden divot that revealed the solution to Mr. G’s puzzle.

Because, by definition, every puzzle has a solution.

So, if I just put my mind to it, maybe there was a solution–one that extracted the steel ring while keeping the two horseshoes united.

Whole.

Intact.

I still believed that most people are good. When faced with the wrong and the right thing to do, most people will at least want to do the right thing and that want was, I determined, a sound enough platform to invest my faith. I also wanted to take responsibility. I started to investigate what bias prevented me from seeing the other side? The only way to really know this, though, was to reach out to “the other side.”

By that time, I had a modest following on Instagram (around 10,000 followers). The word “influencer” barely existed, yet, but maybe I could extend an olive branch, show people what it was like inside my own American home, demonstrate that the spine of our country was made strong, not weak, by families that spoke Korean at home, had kimchi fermenting in their fridge, watched Korean dramas after catching the evening news.

That my parents, who tutored their kids in Korean, also sent notes to their daughter’s school teachers, asking for guidance on her trouble with spelling. That they bought their self-professed “American” daughter a Cabbage Patch Kids lunchbox they subsequently filled with PB&Js and potato chips, a juicebox that came with a tiny, foldable straw. That they dropped her off at college, pressing down the grapefruits lodged in their throats, wondering at how quickly a little girl could grow into someone large enough to carry a stack of cardboard boxes into a dorm room.

I wanted to show people that things could be very different, but also very much the same for those who called this country home. So, I started to share stories. Beginning with one about my mom:

By the time you read this email, my mother will have turned 75–her birthday is on July 13. I thought for this week’s newsletter, I’d share a short story about my mother. But, it actually starts with me and my father. 🙂

Study Time.

“Joanne. It’s study time.” My father would drop this edict with relative regularity on Saturday mornings, after he came home from work. I say “relative” because it wasn’t every Saturday. For example, in summer, he’d often replace the “study time” for “exercise time,” which was his code for “tennis.” Regardless, suffice it to say that starting when I was around 6 years old, my father began tutoring me.

Our Skokie house was a ranch style home–one floor with a fairly straightforward and modest floor plan: a living room, dining room, kitchen in front, connected by a short corridor to three bedrooms, two bathrooms, and, appended at the back-end, a “family room” (sometimes referred to as a “rec room” in non-Midwestern parts of the U.S.). The family room floor was covered by a large rug, housing a sectional sofa facing a large screen TV bracketed by two ugly speakers. In front of the sofa was a square, wooden coffee table.

I always hated sitting on the sofa–my mother insisted on keeping its protective plastic cover and it always made these embarrassing squeaking noises when I moved. I much preferred sitting on the rug, and that is where you’d find me during my tutoring sessions. On the rug, seated next to my father, a stack of books and a spiral-bound notebook in front of both of us.

For the first year, my father taught me Korean. 가갸 거겨, 바뱌 버벼, and so on and so forth. These were the equivalent of A, B, C, D… I found it rather cruel–uselessly cruel–to subject me to a whole other alphabet when I had barely managed to learn the first one. “A is for apple” was still a rather fresh memory as a first grader, so the introduction of so many strange looking letters and my father’s relentless and quite methodical instruction soon grew to be one of the most loathsome activities of my childhood.

And, as I said, I thought it was useless. Strictly speaking, Korean was growing rather passe in our household, ceding much of its territory to the new and shiny English. No one spoke Korean at school and the only person who continued to speak Korean at home was my grandmother. I wasn’t planning on writing her any letters anytime soon, so what was the point?

But Daddy insisted. Actually, mandated is a better word for it. Despite a lot of whining, complaining, and even foot-stomping, my dad employed the time-tested method for handling all of it:

He ignored it.

And thus, despite all my misgivings, sitting here today, I can read and write in Korean.

Thanks to my father.

Swimming In a Dream.

Ping.

It was a text from my mom.

I was sitting on the floor of my tiny kitchen. My dogs, Daisy and Rudy, sidled up to me, wondering what brought me to the ground of our condo. I turned away from the phone–didn’t bother reading Omma’s text–and, instead, buried my face in the curly soft crowns of my dogs.

Then started weeping.

It had been 13 days since I’d been dumped. I’d clearly transitioned from the surreal, “feels like I’m swimming in a dream” stage of denial into the “I can’t stop crying because I’m panicked that he won’t take me back” phase. The collection of unwashed wine glasses in the sink and the box of chocolate truffles that sat open on the kitchen counter was all the evidence one needed of my first experience with being a “dumpee”–I suppose even in my state I wanted to make sure I really aced the part.

All jokes aside, though, getting dumped by Anthony (my now husband–yes, we eventually made up, but that’s not the point of this story) remains one of those ugly scarring experiences. Wine and chocolate truffles were the extent of my diet those days. My eating disorder went into overdrive–I lost 10 lbs in about 3 weeks, a lot of hair, and was freezing cold all the time. I broke out into a stress rash, ended up on antidepressants to help me sleep at night, and had my therapist on speed-dial (Colette was often the first phone call I made in the morning).

Work? Oh yes, I still had a job. But it was December and therefore, none of my clients needed very much. I’d get to my office as late as I could, clock in the obligatory number of hours I needed in order to make my annual quota, get back to my irritatingly sterile condo, crawl into bed, still in my office clothes, right before I’d knock back a couple Lexapros with a few sips of cheap chardonnay, and then cry myself to sleep. Until I woke up, called Colette, and started another 24 hours in what was feeling like an endless loop of miserable days.

One thing I wasn’t doing?

Taking calls from my mom.

People handle loss in different ways. As you can tell, I was handling it in a typically toxic fashion. I was starving my body, choosing, instead, to fill it with alcohol and pharmaceuticals, and avoiding any and all meaningful contact with the people who loved me, whose love for me would remain unyielding and true.

I couldn’t bear their love in my grief.

Does that make sense?

My brother and sister-in-law, who lived with me at that time, gave me a lot of space. Although, I’m almost certain that my sister-in-law, who wears her heart on her sleeve, wanted very much to barge into my room as I sobbed every night, to drag me out into the kitchen, where she would commence stuffing my face with ramen and tteokbokki and chocolate cake from the Italian restaurant we loved. That is, until she realized that my cruel boyfriend, or, should I say, ex-boyfriend who’d broken my heart was also Italian. And also loved chocolate cake.

But my brother Jaesun, after decades of watching me self-destruct, knew to stay out of my way. That eventually, I would emerge from the rubble when I was ready to at least pretend to be a human being again. I can literally hear him, in Korean, telling my sister-in-law, “Jungah-yah… she needs to be alone.”

My mother, on the other hand… well, she was going to mom no matter what.

Hence the phone calls, text messages, and even emails.

I knew she was worried about me, but there was nothing I could do about that. Listening to me hiccup and blubber through the phone or, worse yet, watching me collapse into a heap of heartbreak on the kitchen floor–this was not going to assuage her understandable anxiety. I thus determined that avoiding any communication with my mother was better than broken communication with my mother.

Dear Sun Young.

A few days later, I received a delivery–a bouquet of fresh flowers. Of course! He always loved picking out flowers himself for me! It was something he took pride in! My heart nearly exploded out of my chest: finally!!! Anthony had come to his senses!! And all would be right again!!! I set the beautiful bouquet down on the kitchen counter, right next to a still open box of now stale chocolate truffles. With shaking fingers, I pulled the small white envelope from the plastic prong that held it inside a cluster of baby’s breath, tore it open to unveil the card inside.

It wasn’t from him.

I almost threw that bouquet out the window.

It was from my mother.

I shut my eyes, took a deep breath. Peered down at the small white card nestled in my trembling hands.

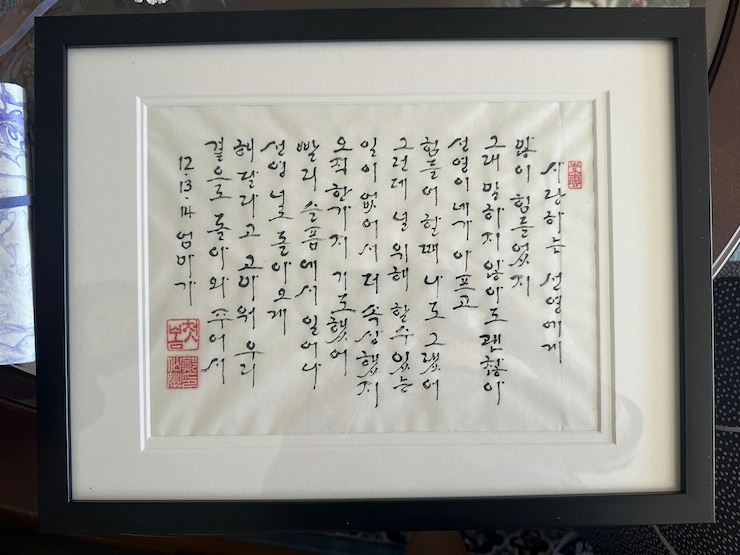

It was in Korean:

사랑하는 선영아

힘들었지? 그래 말하지 않아도 괜찮아.

선영이 네가 아프고 힘들어하는 며칠동안 나도 그랬어.

그런데 내가 널 위해 할수 있는 일이 없어서 더 속상했어, 오직 한가지 하나님께 기도했어.

빨리 슬픔에서 일어나 선영이 너로 돌아오게 해 달라고.

고마워, 다시 우리 모두의 곁으로 돌아와 줘서.

My beloved Sun Young,

It’s been hard hasn’t it? It’s ok if you say nothing.

I know you’ve been suffering for some time now and so have I.

But it makes me crazy that there’s nothing I can do for you, so I just keep praying.

That you will quickly rise up from your sadness, that you can return to us.

Thank you for returning to all of us.

None of which I would have been able to read or understand were it not for my father’s tutoring.

Thoughts on This Week’s Newsletter?

This Week’s Recipe Inspo.

When life gives you zucchini…. you make zucchini tart!

The Korean Vegan Recipe Box

Recipes You May Have Missed…

Heart Healthy Savory Oatmeal.

If you’re looking to spice up your breakfast, this Savory Oatmeal or Bibim Oatmeal will fit the bill!

15-Minute Spicy Tteokbokki.

“Made this a few weeks ago and making it again tonight. Very authentic and delicious.” – Shannon.

What I’m…

Watching.

Well, I finished Bridgerton Season 3 and was feeling so forlorn at its conclusion, I went right on ahead to Queen Charlotte. Of all the Bridgerton-y stories, I’ve found this one to be the most compelling. It is, however, quite tragic and hard to watch. If you are at all familiar with the love story between Queen Charlotte and King George III, then you already know what I’m alluding to…. so be ready. But definitely worth the tears!! Watch Now!

Reading.

Like you, I subscribe to a handful of thought provoking, smile-inducing, and/or useful newsletters (I hope mine hit all three of these…!). One of them is the weekly newsletter by Hello Sunshine. It’s always full of tidbits that inevitably leave me feeling… inspired? motivated? empowered? Like I can go forth and conquer the world or something! If you haven’t subscribed already, definitely add a little bit of sunshine to your inbox! Subscribe!

Loving.

I’ve been a fan of HexClad for a few years now, but my 12″ non-stick came in especially handy the other day. I was making some zucchini pancakes and tried making them in a NOT HexClad pan. BIG mistake. The pancake turned into a mushy mess! I also like these pans for oil-free cooking. I’ve been making my “fried” rice in their non-stick wok and it works fantastic with vegetable broth! Shop Now!

The Korean Vegan Kollective

Join now to discover a world of culinary inspiration at your fingertips.

Use code TKVSUMMER20 at checkout for $20 off the annual membership price.

Parting Thoughts.

Oxford Dictionary defines “language barrier” as “a barrier to communication between people who are unable to speak a common language.”

As I grew older and the Korean words that used to spill so easily out of my mouth seemed to leak out of my brain, the language barrier was often blamed for the… misunderstandings between myself and my parents. And I didn’t even have it that bad–both my parents spoke fluent English, after all. It was still their second language, though, and it wasn’t easy for them raising an extremely precocious daughter whose lexical catalogue surpassed their vocabulary by the time she reached junior high. It also didn’t help that I often liked to remind them of my linguistic superiority as a way of getting back at them for stupid things like not letting me go to the mall with my friends, refusing to buy me a pair of Birkenstocks or Doc Martens, marching me back into my room to study when everyone else was having fun at the beach.

“Never mind,” I’d mutter loudly enough for my mother to hear. “You wouldn’t understand me anyway.” And I knew that she knew that when I said “understand,” it was that she literally would not know the meaning of the words I’d hurl at her.

“You think I’m so stupid, don’t you…?” would be her quiet retort.

I didn’t think my mother was stupid, per se. But I did think she was ignorant, wrong-headed, selfish, and altogether untrustworthy. Even though she was the one who introduced me to Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Hemingway, and the Bronte sisters (authors she fell in love with when she was in middle school), I somehow still viewed her as “uncultured” simply because she couldn’t translate fancy words like “oppression.” But rather than leaving it as merely a failure to translate, it was much easier for my as-yet-undeveloped brain to conclude that Omma’s inability to understand that particular English word also meant that she couldn’t understand its meaning, the actual concept either. Why else would she force me to stay at home and study instead of frolicking at the beach?

Hence, the small gaps that emerged between me and my mother when I started speaking more and more English widened into a gulf, until we were separated by far more than the thin pages of a dictionary.

Time and distance certainly play a role in helping to construct a bridge, one that can hurdle a language barrier. And of course, even if English wasn’t a language we could always speak together, because we loved each other, we developed other languages we had in common, languages that didn’t require words at all. In some ways, Omma’s most powerful expression of love to me was symbolized not by three iconic words, but by the sight of the small lamp above her front door, flickering to life, no matter the hour, no matter the reason, whenever I needed sanctuary.

I’ve spent the last several years of my life excavating my mother’s story. No, not my mother’s story, but Sunny’s story. To reconstruct the woman who erased herself to be my mother, who learned an entirely new set of words so she could build a life for me here in America. I have shared so much of what I’ve unearthed with all of you–even if it didn’t always cast Sunny in the best light. My mother’s willingness to divest her ego for the sake of truth, and all that truth can achieve when it is permitted to thrive beneath the bulwark of compassion, humbles me beyond words.

I sometimes wonder what would have happened had my father not insisted on teaching me to read and write in Korean. What would have happened if I hadn’t gone vegan, started The Korean Vegan, begun peeling back the layers of my family’s history? Where would I be if I’d kept those stories to myself?

I rattle the chain between my hands. Let the weight of the horseshoes settle against my palms.

And tell myself, once more, there is a solution to this puzzle.

Wishing you all the best,

-Joanne

Comments & Questions.

July 15, 2024

Dear Joanne,

Thank you for this week’s podcast episode. You are so right when you speak of how the love we give and receive is more than the words we write and speak. I am also pulling back the layers and learning my parents’ stories too in my 40s. I think it took me this long to see my parents as people, as a man and woman with desires, dreams, and hurts like me. And maybe hiding behind the excuse that our Korean language doesn’t quite add up to theirs and that’s why we call it a language barrier and as long as there is a barrier, it also deems we have done our best and there is nothing we can do about this barrier that separates us by our differences.

Because, it take more courage to see the love that is given and openness to see it again.

Also, this gift from your omma is beautiful.

KH, thank you so much for reading! And I relate so much to the struggle to see our “parents as people.” I think it’s even worse for me since I don’t have kids of my own? And therefore can’t empathize with the loss that comes with parenthood. But like you said, “we have done our best.”

You are a beautiful, inspirational, caring and extremely interesting person. Love and Happy Birthday wishes for your Mom!! Much love, Barb

Thank you Barb!! I very much appreciate this and I know my mother is grateful for the birthday wishes!

As always, I adore your stories, especially the stories about your parents. And I was so glad to hear that it’s your Mom’s Birthday, I am EXACTLY 2 days older than she is, I turned 75 on July 11. So we are almost birthday sisters. Your parents love for you just shines through these stories. Please keep sharing, they re meaningful and relatable. Oh, and thanks for the yummy recipe!

OMG Happy Belated Birthday, Colleen!! I hope you did something fun and that were with people you love. And can’t wait for you to try the recipe!

This has to be one of the most exquisitely beautiful things I have had the privilege to read.

Mary, <3<3<3

Dear Joanne,

I am so grateful to you for sharing your family’s stories. They bring tears to sobs as I read. Your skill as a writer, your hard worked self awareness, honesty and enormous heart, is an immeasurable gift to us all.

I have been doing a deep dive into Korean culture the last year and a half. My daughter/friend introduced me to my first Korean drama and I was hooked. My gateway drug to Korean culture. I too, adopted a plant based diet 7 years ago and so much wanted to cook authentic Korean food just without the animal products. I have found your cookbook to be so incredibly helpful. Kimchi is now, always in the fridge, and Korean scallion pancakes, braised tofu are regularly on the menu in our home. Thank you for helping me navigate ingredients like gochujang, gochugaru, and doenjang as I live close to the boundary waters in Northern Minnesota on Lake Superior. No close Korean grocery for hundreds of miles. Your explanation on what ingredients can and cannot be substituted is important in building a pantry.

I am reading, listening to podcasts about Korean history, (beyond horrified about the Imperial Japanese occupation), beginning to learn the Korean alphabet

I am so grateful for the courage of your parents to make the decision to come to this

country and raise a family. I honor their sacrifice. Please say happy birthday to your Omma and many happy years to come!

Mary!! I just love this message so much. Your earnestness is such a testament to what makes love and life so worthwhile. Hopefully, one day, you will share what your first k-drama was?? (Crash Landing…??) And that it is has led you to Korean food and culture is all the more exciting. I will definitely pass along the birthday wishes to my mother–she always gets excited when she hears ppl using doenjang!! <3<3<3

Beautiful stories. What a great gift from your father. One of my biggest regrets is that my parents didn’t teach me any of the native tongues that they speak. And growing up in former colonized countries, it was a source of pride for me to speak superior English. It also made me foolishly look down at those that spoke their native tongues and didn’t have the mastery over English that I did. Today, at my age and with my kids, I wish I could speak the languages fluently and that I could impart that to my children. It’s great that you are able to acknowledge your father’s gift and how it unlocked so much for you later in life. Neither of you could have imagined the profound impact it would have on the arc of your journey. I think another implicit gift for you in his teaching is that you are today able to embrace authenticity in all its forms – yourself, your heritage, your roots, your relationships. Loved the stories.

Thank you Hammer!! I didn’t know you did not learn your native language growing up. But I totally relate to the pride in assimilation. That was very much the case in our house growing up, EXCEPT for my Dad’s insistence on learning Korean. And I am so grateful for that gift, as you say! And very true–I think language plays a vital role in empathy, which always leads to a pursuit of truth. Thank you for reading, as always!

Love your journey. Never let the haters get to you. Love your recipes too.

Thank you Michael!!

Dear Joanne,

Heartfelt happy birthday wishes to your mum! Many happy returns to her!

Thanks for sharing this beautiful story. There´s so much love in this!

The stories our hearts tell are so much more important than the words per se. But it does help to develop a vocabulary and literacy – and be willing to learn, listen and understand.

I LOVE the theme of „returning“ towards connection.

Thanks for sharing your wonderful stories, generally – we need humanness literacy, to help us all return to connection.

With much Love,

Cornelia

Cornelia,

First, I must say, I LOVE your name!!! I sometimes write under the pseudonym “Cordelia” because I find it so romantic. 🙂

And I agree so much with what you said about “returning” towards connection. What an astute observation–the connection point in my mother’s note, as well as in everything else. I didn’t even pick up on that myself. But, it also raises a larger thought/potential discussion on the role that grief, pain, heartbreak can play in DISconnection…. until, of course, those things are molded into empathy and compassion.

Thanks again, Cornelia, for this thoughtful comment!