North Korean Sports Diplomacy and Korean Cold Noodles.

Listen to this week’s newsletter on Spotify, Apple, or wherever you get your podcasts!

Olympic Diplomacy.

For the first half of August, the Olympics have allowed us to witness all manner of extraordinary, almost inhuman levels of athletic achievement. The Games have also provided a welcome respite from much of the heaviness that has pervaded global politics over the past several months, even as the U.S. heads into the final stretch of its general election season.

While Simone Biles, Katie Ledecky, and Novak Djokovic have dominated the Olympic headlines, percolating just beneath the radar are all sorts of smaller stories, ones that may not be covered by splashy newspapers, but still go viral on TikTok. One of those stories I discovered while scrolling through Threads.

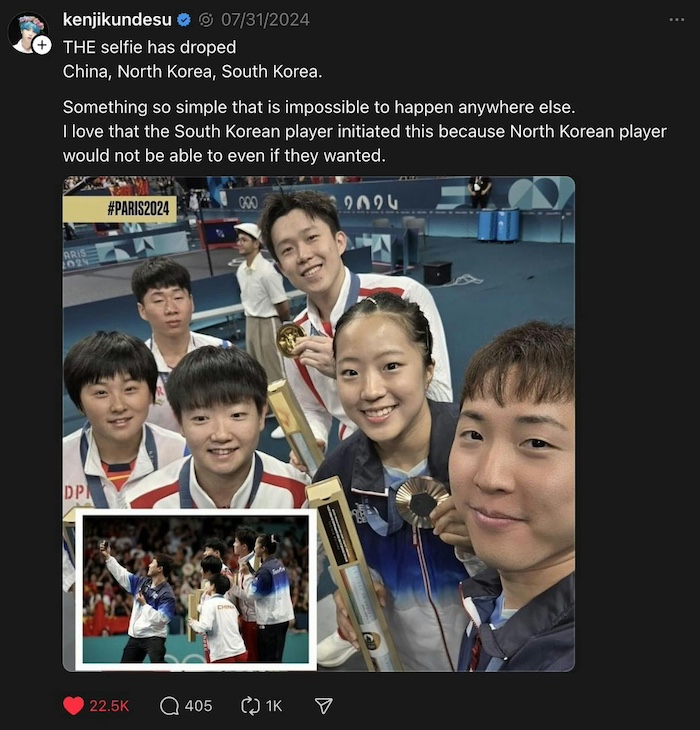

Someone posted a photo of South Korean Bronze medalists in doubles table tennis taking a selfie with the North Korean silver medalists and the Chinese gold medalists. According to one social media post on China’s Weibo, “This should be the most meaningful picture of the Olympic Games!” Another popular content creator, @kenjikundesu, posted, “THE selfie has droped [sic] China, North Korea, South Korea. Something so simple that is impossible to happen anywhere else.”

Indeed, given North Korea’s 8-year absence from the Olympic Games, it had been a while since the world was graced with anything resembling normalcy vis-a-vis North Korea. It was also a reminder that we still know next to nothing about the lives of these athletes, their families, or the roughly 26 million people living within its heavily guarded borders.

North Korea became a topic of conversation, again, a few days later, with a viral TikTok (over 14 million views), featuring a young gymnast side-eyeing Simone Biles:

Selfies with fellow medalists, a shy side-eye at the GOAT–on one level, these things are totally “normal,” even cute and endearing.

But on Threads, the commentary took a darker turn:

“This child is from North Korea. Y’all need to stand down because she and her entire family would be punished if she showed ANY positive behavior or admiration for an American athlete. Learn and do better.”

“I saw this, and the first thing I thought was ‘I hope she doesn’t get into serious trouble for even that look.’ Also good for Simone for not engaging with her because that could be her & her family’s life.”

“North Korea probably doesn’t want to have any of its athletes get too chummy with outsiders, for fear they will develop connections that will help them defect. Those poor athletes are watched like hawks, and have to watch every step they take. And I shudder to think of what happens to the ones who don’t win anything. Pretty sad!”

And even the heartened Kenji noted, “I love that the South Korean player initiated this [selfie] because North Korean athlete would not be able to even if they wanted.”

Kenji was more accurate than I think even he realized. North Korea did make headlines at the Games–not because of their medal collection, but because unlike all the other athletes in the Olympic Village, North Korean athletes were the only ones who were not furnished with Samsung smartphones.

Why?

According to South Korea, the provision of smartphones to the North Korean athletes would have constituted an impermissible UN sanctions violation. (See CBC Article.) Specifically, the UN prescribes the provision of any items that can be used “for a nefarious purpose.” (Id.) Apparently, something as innocuous as “equipment used to make baby food, for example, can be repurposed for biochemical weapons.” (Id.)

Hence, while all other Olympians will be headed home with a free smartphone, the North Koreans will be going home without one. One expert opined that they wouldn’t have been much use anyway, since they are not connected to the internet and, moreover, they are not permitted to download the variety of apps and programs that crowd our phones.

The omission of smartphones isn’t the only difference between the North Korean Olympians and the rest of those milling about the Olympic Village: “They probably have security guards and others following them. They’re not free to explore wherever they want in Paris, for instance,” said Tina Park, the CEO of Park Group, an international security consulting company. “Whenever a North Korean delegation is abroad, they are carefully watched.”

Every time I see North Korea participating in the Olympics, a mix of emotions rumbles through me. On the one hand, like Kenji, I allow myself to indulge in a few moments of hope, a sharp optimism that bursts through decades and decades of gaslighting. But inevitably, the burst dissipates, snuffed out by a pattern of behavior that has become depressingly familiar. Whether it’s Kim Jong Eun, or his father before him, dictators are going to dictate, fascists are going to fascist. We are allowed a brief glimpse at a potential future, what it could be like, what it was once like, before it’s cruelly torn away with a crook of a finger or a conflagration of despotic rage.

And once more, I remind myself that trying to predict the behavior of a sociopath couched in words like “strategy” or “policy” is largely a fool’s game.

Crash Landing.

The other night at dinner, a friend of mine (non-Korean) asked me what I thought about North Korea’s participation in the Olympics. I took the question to mean what I think most people wonder: “Do you think the peninsula will ever be whole again?” Or, at least, that is the question I always hear, whether it’s formulated that way, literally, or more vaguely, as I assumed this one from my friend to be.

I shrugged over my bowl of half-eaten bibimbap. “I mean, who can say? You can’t really guess what a dictator is going to do.” And in my head, I thought, “You just feel sorry for the people who live there.”

“The people who live there.”

Honestly, it wasn’t until I watched a very popular Korean drama, Crash Landing On You (a typically light-hearted drama about a very wealthy South Korean woman who lands in North Korean territory in a freak paragliding accident), that I ever spent any real time thinking about the people who live in North Korea. This is despite knowing that my own parents were born there. On some remote intellectual level, I knew that the people were living under horrible, unthinkable conditions, caught between the thumb of a brutal authoritarian regime and the crushing weight of international sanctions.

But until Crash Landing, I never thought about how drawn the North Korean accent was, in stark contrast to the roundness of Seoul dialect, as if their speech was a product of the shape of their faces–on the one side, long and starved for the abundance of curling one’s tongue around a fatty morsel of food, while on the other side, curved and full, accustomed to the slurp of Boba tea and creamy pasta. I also never considered how they might be as addicted as I am to dramas, how they too might be waiting, week to week, to watch a pirated copy of Love from Another Star, the one they picked up from the black market, along with a bottle of collagen enhanced shampoo.

More recently, I watched another Korean drama–a whimsical and slightly dark superhero story, called Moving. In it, the good guys and bad guys are organized, predictably, on either side of the 38th parallel. However, the “bad guys” (i.e., North Koreans) are provided with rich back stories, ones that break your heart with their agony, even as you want them to lose.

And I realized, I never gave much thought to their suffering. The desolation residing in and extending out of their hearts, the unavoidable bleakness that attends many lifetimes of living in poverty and fear. The illness that must emerge when every attempt at living a life on the most fundamental level–procuring food and shelter, finding companionship and love, protecting your offspring on the belief that the future is filled with possibilities–is thwarted by the profound narcissism and greed of one man who seems to derive pleasure from hurting the people he proclaims to protect…

You begin to realize how much is erased when the stories of an entire people cannot be told.

Last year, I had the opportunity to meet with Sean Chung, the CEO of HanVoice, a Canadian non-profit committed to facilitating the resettlement of North Korean defectors. Sean has been working with North Korean refugees for almost his entire career. I asked him all the questions I had about North Korea, and he confirmed that many of the things we’ve assumed are correct.

Starting in the 1990s, after a terrible famine, “North Koreans were pouring out of the country, and as a result, you heard stories of North Koreans being forcibly repatriated or returned back to North Korea and they would face punishment for leaving.”

Penalties are not limited to those attempting to flee. Those who enter North Korea also risk detention. Sean recounts, “Our senior pastor was detained in North Korea for two years.” Sean continues, “He had been involved in humanitarian activities since 1997 and had made over a hundred trips.” Why the sudden hostility? Sean attributes it to what he calls a “shift” in leadership:

“When the current leader [Kim Jong-un] came into power, there was, I think, a kind of shift in leadership. It was part of a purge that happened when he killed his uncle. The pastor who had ties to the previous regime or previous version of the regime, was obviously caught in the middle of that. So he was detained for two years.”

In other words, a man lost two years of his life–removed from his family, church, and country–not because he did anything wrong, far from it. But because he got caught in the crossfire of two warring regimes.

I distinctly remember when Kim Jong-un assumed leadership after the death of his father, Kim Il Sung. At the time, ensconced in the sweeping and secure abundance of America, we joked about it, calling the mad dictator-to-be “Jong-un-ee,” using the diminutive to refer to him, essentially, as “little brother.” It was easy to joke about him; in fact, there was a thrilling sort of power in utilizing the ancient hierarchy embedded in Korean culture and language to belittle “Jong-un-ee,” the chubby son of the deceased man who was once one of the most feared dictators on the planet.

But the reference to little “Jong-un” was also an oblique allusion to hope, one that we didn’t even put into words, lest it evaporate at the audacity of its enunciation. Maybe this younger, chubbier dictator wouldn’t be so bad. Maybe a change in regime also reflected a change in heart. And at times, that hope was given a chance to breathe:

“Before the pandemic… there was more openness, particularly with the summit diplomacy between Kim Jong-un and Donald Trump. There was this feeling that things could change and, I think inside the country as well, you would have a flow of information going into the country. You had North Koreans who had the latest episode of Game of Thrones, maybe a week after people outside of North Korea would get these dramas,” Sean describes.

In the same way Kim Jong-un represented a new generation, “you had this sense of a new generation of young people of North Korea who were driven by making a profit and not by any kind of real ideology,” Sean explains. “You see this great growth in the people’s power and agency and then the pandemic happens.”

The New Dark Ages.

Sean continues, “North Korea, in January of 2020, was one of the first countries in the world to shut down its borders.” To many, the level of isolation that the north half of the peninsula plunged into heralded the “new dark ages for North Korea.” According to Sean,

“It wasn’t just that the North Korean regime closed its borders. It’s the fact that they realized that if they could have more control over their population, this was the time…. When the pandemic happened, they realized, ‘oh, this is a window of opportunity.’ And so, in 2020, they put out this anti-reactionary thought law, which is basically a law that criminalizes and puts high penalty on accessing information, outside information.” These anti-reactionary thought laws that penalized access to news and media from the outside world went into effect at the same time that the regime was “installing surveillance cameras on the borders” and electric fences designed to keep people in and to keep information out.

The pandemic provided a convenient, built in excuse for closing themselves off to the world: “They didn’t need to open up their borders anymore. They didn’t need to invite any foreigners into the country…. All diplomatic staff left North Korea. All foreign humanitarian organizations left the country. The country was sealed off until very recently.”

What was the impact of this new age of isolationism? Only 63 people made it out of North Korea in 2021-2022, compared to the over 1,000 defectors in 2019.

How was the world alerted to the regime’s recommitment to such an isolationist foreign policy?

Crash Landing.

According to Sean, “we heard reports of Crash Landing on You, which … aired right in between pre-pandemic and post-pandemic…. And so, we heard reports from folks who were inside the country that really wanted access to the next episode…. It’s not just about North Korea having these draconian measures and a lot of the things that we’re hearing now; but, it’s just a simple kind of way of looking at that feeling, when you can’t–when you don’t know, when they leave you on a cliffhanger at the end of a Korean drama.”

This is the story that’s missing from everything we see and hear about North Korea. As Sean eloquently describes, “When you google North Korea, you see images of missiles, you see images of Kim Jong-un, you see images of the kind of propaganda…. those are the only images the State authorizes of North Korea. And so, when you google North Korea, you’ll find that it’s mostly of one person and the actions of one person. When you google South Korea, you have beautiful images of landscapes, of cityscapes, of people…. What dramas like Crash Landing on You do is to humanize the North Korean people. And to dispel the myth that they are some other person in some alien world. When we think about North Korea, we should be thinking about the North Korean people.”

But as Sean put it, “we don’t really know” what’s happening inside the country, what the everyday lives of the North Korean people looks like. Only “glimpses.”

Anthony and I actually had the privilege of meeting with and hearing from recent defectors from North Korea at last year’s fundraising event for HanVoice, including an individual who used to serve in the North Korean military. I will never ever forget how he described standing guard at night atop a hill overlooking the DMZ with a clear view of both halves of the peninsula. On one side, South Korea glowed with its electric lights, while on the other side, North Korea was enshrouded in a quiet darkness. And he thought to himself,

“In South Korea, electricity is used to light the country. In North Korea, electricity is used to keep everybody in.”

Thoughts on this week’s newsletter?

This Week’s Recipe Inspo.

Cold Korean Noodles!

More Noodles Recipes

In Case You Missed It…

Many of you signed up for this newsletter on the promise of some Mediterranean Toast, but signed up AFTER last week’s newsletter already went out! Well, I don’t want you to be left out of the toast fun, so here it is! My Mediterranean Toast!

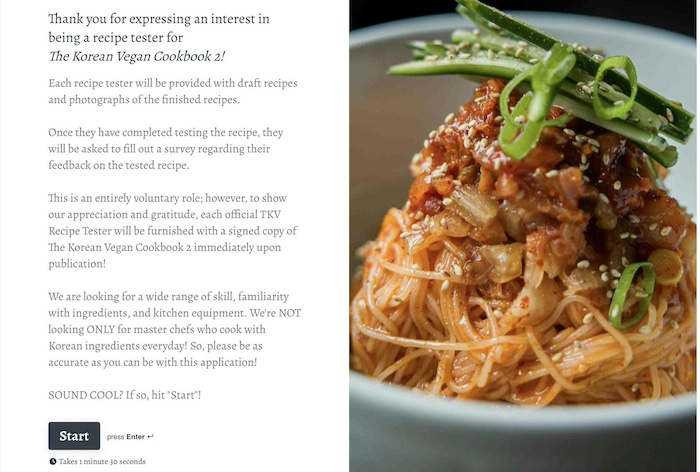

Recipe Tester Application.

WOW!! I did NOT expect so many responses to my request for recipe testers for TKV Book 2! Thanks! Suffice it to say, I was OVERWHELMED!!! Instead of responding to each email one-by-one (which would take me weeks!), I’ve created a small survey for you to fill out, mostly just to get a little information on your experience and access to Korean ingredients, as well as to confirm you are still interested.

Click the link below to fill it out!

What I’m…

Watching. I have been anxiously anticipating the final season of The Umbrella Academy, a dark, hilarious, and slightly obtuse anti-hero Netflix series. I was bummed to see there were only 6 episodes (there are usually 10 episodes), but, overall, quite happy with the final season. It was so nice to reunite the characters I’d fallen in love with and it was over far too soon–a sign that the show had NOT overstayed its welcome. Watch Now!

Reading. Guys, I was crying in the back of my Uber within the first three pages of Tembi Locke’s From Scratch. This book is beautiful, powerful, and a master-class in lyricism and poetry. Locke writes about love and grief in a way that is so palpable, it physically hurts to read her words–in the BEST way. This book is SO GOOD, Anthony is reading it in Italian!! Whether you’ve already watched the Netflix show (I haven’t) or not, READ THIS BOOK!!!! Read Now!

Loving. I recently had the chance to try some deli “meat” made out of mushrooms and was UTTERLY BLOWN AWAY LIKE OMIGODS SCIENCE. If you guys missed chowing down on a simple, easy to make deli sandwich, check out Prime Roots. They don’t sell direct, but I got mine from Vreamery! Shop Now!

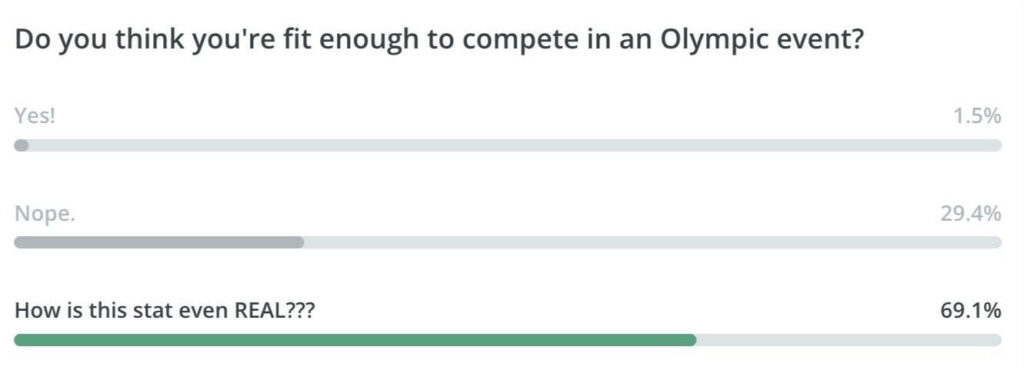

Last week, I mentioned that nearly 40% of Americans believe they are currently fit enough to compete in an Olympic event. We then did our first fun poll here to see how many of you think that you could compete in The Olympics! the results are not surprising….:

Like me, most of you thought the stat had to be a FAKE, LOL! But, also, I am SUPER EXCITED to know that there are people in my newsletter community who are presumably EXTREMELY FIT!!!

Parting Thoughts.

As many of you know, my mother was born in North Korea. But Omma was only one year younger than the country of her birth: the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (aka North Korea) established itself on September 9, 1948. Omma was born just ten months later, on July 13, 1949. Shortly after she was born, she and her family fled the newly formed communist regime and started a life, as refugees, in South Korea. During that time, her father, my grandfather, was conscripted into the war, fighting on behalf of the Republic of Korea (aka South Korea).

Can you imagine? Being forced to fight in a war while your wife and two infant daughters had to fend for themselves as refugees? Being forced to fight in a war against the people you called your own countrymen just one year ago? Being forced to fight in a war alongside a bunch of foreigners, people who knew nothing about the home you left behind, the family you’d never see again?

My father, too, was born in North Korea, only when he was born, North Korea didn’t even exist. His father fled the northern half of the peninsula on August 16, 1945. How do I know this with such specificity? It was the morning after “V-Day”–“V” was for victory, as Omma often told me when I was little, and “victory” was South Korea’s hard-earned independence from Japan.

So Daddy and his mother, my grandmother, were left behind in the North, while grandpa fled to the South. Eventually, though, my grandmother strapped my father, still an infant, to her back, slogged through the deep mud of abandoned rice paddies, and found a way through the mountains that were daunting, yes, but far easier to hurdle than the imaginary line that would soon divide a country she’d only ever known as whole.

Can you imagine? Being a single mom in the middle of a war? A war that isn’t some far-off, distant dispute between two countries you can barely pronounce the names of, but a war that’s literally tearing apart the only ground you’ve ever known? Being forced to submerge your baby’s head beneath the filthy black water of a rice paddy to get past a soldier at his post, his still figure silhouetted by the soft glow of the moon? Being forced to walk for days and days and days with that baby, watching his face shrink because you’ve run out of breastmilk and food and even water?

You can imagine. I know you can. Because I can. Because I’m here, to tell you about the North Korean people who make up a part of my family, a part of who I am.

What I can’t imagine, though, are the stories that don’t make it out, beyond the electric fence, into the light.

Wishing you all the best,

-Joanne

Mary, I think it’s easy for us to forget that it used to be just one country one generation ago… And the kind of trauma the division can cause for millions and millions of people. I think about that a lot when my mom and dad act a little… strange!! I remember that I can never ever truly appreciate what this did to them and that compassion is the most powerful act of love I can give them. Thanks for reading, Mary!!

I have often wondered how one country can be so different from another. In this case your article is very poignant. When I think about the people of North Korea it makes me very sad.