Mental Health.

Read Ep. 26 | Show Notes

Subscribe Below to Receive the TKV Newsletter in Your Inbox

My first conscious brush with mental illness occurred when I held my Gomoh’s hand for the first time. I was 8 years old when Gohmoh (which means “paternal Aunt” in Korean), my father’s second younger sister, came to visit us in our Skokie house.

As I clutched at my new Aunty’s left hand, I discovered she had only four fingers.

When I asked Mommy why Gomoh was missing her pinkie, Omma answered,

“Because she sliced it off with a knife.”

I swiveled my head at the answer, but Omma was busy doing something or other in the kitchen.

“Why would she do that? Didn’t it hurt?”

Omma shrugged. “I guess she was very upset about something. And cutting her finger off made her feel a little better.”

At the time, this was the extent of my exposure to mental illness. My Gomoh was kind, patient, and, yes, a little quirky. But, I loved her in the way that children love new toys–and as she emerged each morning from the small bedroom at the back of our home, she brought with her a sense of adventure that attends the unknown. My most vivid memory of Gomoh is how she often tried to cook for me and how I ate every last drop of her somewhat bland, not terribly good food because I didn’t want to hurt her feelings, because it must have been extra hard for her to cook with only four fingers on one hand.

When I was much older, my mom described that, during Gomoh’s visit, she once woke up in the middle of the night to some unusual noises in the kitchen. She ghosted down the corridor, still in her nightgown, only to discover Gomoh pacing back and forth atop the linoleum tiles, wielding a kitchen knife. When Omma asked her what on earth was the matter, Gomoh replied,

“God told me that Satan is in this kitchen and that I must kill him.”

Exorcising Our Pain.

Even though I understood, implicitly, that there was something strange, even dangerous about a woman who would cut off her own pinkie, I certainly had no way of knowing at that time that my Gomoh suffered from schizophrenia–something I would learn about several years later when she was ultimately hospitalized for her illness. I would also come to know that the idea of harming one’s physical body to cope with distress was not completely unheard of. One of my aunts on my mother’s side, my Dool-chae Eemo (“#2 Aunty”), purportedly tried to rip her front tooth out with a wrench when she grew upset. She also confided in me that when she was sad, she often sat with her dog outside in the outhouse (in Korea, at that time, many urban homes still had their bathrooms outdoors) and cried.

Of all my relatives, I related most to my Dool-chae Eemo. She looked like me–round, buxom, and stocky. As I grew older, we often joked how she and I were the only women in the family who were blessed with natural T&A (in Korean, of course), as well as long eyelashes. Eemo also had a riotous sense of humor, often making me laugh until I cried; but, as revealed by the “wrenching of the tooth” incident, she was prone to profound sorrow and empathy, crying over (and not just with) her dog, children, and family if she sensed even a modicum of their pain. I related to this part of her, too.

Because she lived in Korea, her influence on me was somewhat limited; however, it was nice knowing that my body shape and size was not a complete anomaly (which is often what it appeared to be when one looked at my tiny, skinny as a beanpole, mom or my very lean and athletic looking dad). And, it was equally comforting knowing that I wasn’t alone in the instinct to cry in the bathroom with my dog when life grew overwhelming.

And, perhaps it wasn’t a coincidence that my first confrontation with my own mental illness came at the end of a fork.

This One Time in Junior High…

I was in 7th grade, which is, in my opinion, one of the most wretched times in a young person’s life. All the sheen of starting junior high (in 6th grade) had worn off and I didn’t have the exciting prospect of leaving for the berth of high school quite yet. I was also going through the hormonal ups and downs of puberty, which manifested in a closet full of black clothing and really thick eyeliner (when my mom would let me get away with it).

Speaking of my mom, this time in our co-habitation was probably among the more restive. We were fighting constantly–about my grades (which were never good enough), my clothes (which she thought were too revealing), and, of course, boys (who, as she made abundantly clear to me, were completely off limits to me until I turned 18 years old). These fights had an unnerving affect on me, perhaps more so than the average fight between a mother and daughter. Each one ended in tears on my side and a cool silence on my mother’s. She called it “the silent treatment,” a tool she’d readily employ to ensure that I wouldn’t soon forget whatever lesson she was trying to impart. I imagine it was also her own defense mechanism, a way of shutting out the source of her distress until she was able to recover her patience and be a parent again.

It was after one of these fights and during one of these “freeze outs” that I took a fork from the school cafeteria, went to the girl’s restroom, and began “scraping” myself. That’s right–I didn’t have the guts to use a knife, and maybe that’s why I was able to tell myself that there wasn’t anything “really bad” about this. I wasn’t “suicidal,” clearly, since I was using a dull fork from Wilmette Junior High School’s cafeteria. I found, too, that the action of focusing so singularly on the pain I was causing to my body somehow leached away some of the pain I felt in my chest. I was doing something about the hurt and if that meant I had to pay for it with marks along my inner forearm and wrist, so be it.

It was also, in all honesty, a cry for attention from my mother. And it worked. The first time she saw the marks along my arms, she grabbed them and told me how silly I was for doing this. She told me never to do it again. I could tell, even then, that I’d caught her off guard, that she was torn between fear and frustration, and thus went back to an old parenting stand-by: “pretend it’s no big deal.”

I didn’t listen to her. I continued to harm myself, even though it never really garnered the kind of reaction I craved. Eventually, I graduated from forks, to knives, to razors. It was a habit I continued all the way until my divorce from my first husband. Eventually, it stopped being about “attention,” and became, instead, a way to control the panic, the abject terror I had for a world that seemed indifferent to me.

That Time In the Locker Room…

It’s hard to describe, even now, what it was I was looking for from my mother when I harmed myself, much less back then when I was still just a big mish-mash of pre-pubescent hormones. It’s not particularly easy for me to write these things down and share them with all of you, because there’s a great deal of shame embedded in these memories, in my desperate and ugly cries for attention–a desire I try to suppress. But, one memory sticks out to me, in its sheer delicacy.

It was in the locker room of New Trier High School.

My best friend, Joo Yon, and I were changing into our gym uniforms. The night before had been a bad one and therefore, my arms were covered in bright red scabs that had barely just formed. I grew careless about hiding them from Joo, and all of a sudden, she grabbed my wrist.

“Joanne. WHAT THE FUCK IS THIS?”

Joo was Korean American, but she spent a good chunk of her childhood in Korea. When she came back to the US in high school, she spoke with a slight Korean accent, one that only a fellow Korean American could possibly detect. So, when she uttered the “f” word, it was tinged with notes from my mother’s native tongue. Before I could even begin formulating an answer, tears began to ooze down her round face.

I was trying to hold back the flood gathering in my throat. It was like she was pushing into the emptiness I held inside my stomach for so long, demanding a seat inside the darkest interiors of my heart.

“Don’t EVER do this again,” she said, shaking my wrist.

I nodded, barely breathing, because I wanted to hold this moment in my hands like a broken bird, feel the contours of its fragile beauty until I memorized them.

Because I knew it would be a very long time before someone ever joined me at that table again.

College Was…Rough.

Suffice it to say, I had terrible separation anxiety. First, from my mom (you may recall the time I missed the bus back home to Chicago, called my mom sobbing from the bus stop, which then prompted my mother to drop everything she was doing and drive 3 hours to pick me up in Urbana, Illinois). And then, from my boyfriend.

I started dating right on cue–when I turned 18 years old. He was my first boyfriend, first love, and, later, my first husband. He was a “super senior” at the time I started college, so he would only be sticking around for one semester before going back to Chicago to start his “adult life.” I was unprepared for the anguish of saying goodbye to him, the constant gnawing on the fringes of my brain, suggesting that certain doom lay around the corner. My body was operating at a 5 out of 5 when it came to anxiety, and as a result, it was only a matter of time before I started doing what I could to find pockets of relief. When cutting myself wasn’t good enough, I started taking over-the-counter sleeping pills, sometimes, dozens at a time. It was the only thing that would “shut my brain up.”

One of those times, my roommate grew worried and called 911. I was rushed to the ER, terrifically embarrassed, but adamant that “I’m not depressed” and was most certainly not suicidal. Still, the school put me on probation for my purported “suicide attempt” and required four visits to a therapist before I was put back on regular status.

[Side note: I remember when I was sitting for the bar, I made an appointment with the Dean of my law school to see whether my status as a “recalcitrant” in college would somehow prevent me from being a lawyer! She laughed so hard when I finished my tale and reassured me that so long as I disclosed all my parking tickets (the State bar is VERY serious about disclosing all your traffic violations!), this little incident could stay safely behind closed doors.]

It was during this time that Omma could no longer ignore the “problems” I was having. Not only was she required to take me to therapy, she struggled with trying to parent me from Chicago. I cannot imagine how agonizing it must have been for her to know that I was getting into trouble, ending up in the emergency room, and placing myself within the crosshairs of the university while she could do little more than observe from hundreds of miles away.

I remember, she did what any other Korean mom would do in that situation–she called the pastor at my campus church. I laugh about this now because it was largely useless. I had a nice conversation with the Pastor, the same man who ultimately told me that I should pursue a career in teaching or healthcare, because my “real job” was eventually to be a mother. Calling him and asking him to help me was such an Omma thing to do, though. But as I look back, all I can think of is how enlisting someone she’d never even met, into such a private space in our lives, evinced the severity of her desperation, how she was grasping at whatever she could to keep her daughter safe.

One Snowy Day in Wheeling, Illinois.

I had my first nervous breakdown right after getting accepted into the University of Chicago Law School.

I know. Why would getting such amazing news throw me into such a tailspin?

I remember the day I received notice of my acceptance. I was at work (paralegalling), when the admissions office called me to congratulate me. That evening, my boyfriend came to pick me up and as soon as I walked out of the building, we held hands and we did the “happy dance” together right then and there. This memory remains one of my most precious, even though it was with someone I would ultimately end up leaving.

It was because I was so happy that eventually I grew unhappy. More specifically, I went to bed that night with an uneasy feeling in the pit of my stomach. “Am I allowed to be this happy?” By the time I woke up, I was convinced that the answer was a resounding “no.” That the aphorism, “What God giveth, God taketh away” was directly applicable to my life and that He would take away the thing most precious to me:

My boyfriend.

I was certain it was only a matter of time before God struck him down with some sort of grave illness or a terrible tragic car accident because there was no way in the world that God would let me have everything I wanted–the man I’d loved since I was 13 years old and a rock star career in Big Law.

It was against this strange emotional backdrop that the world pulled the trigger and catapulted me into what I still describe as one of the most frightening chapters in my life, one that was so terrifying that, for many years, I liked to pretend it never happened, because even remembering its existence was too dangerous.

My boyfriend and I were driving home one evening. It was snowing very badly and all the roads were slippery, so everyone was driving like idiots. I grew impatient with the car ahead of me and was probably inching closer than I should have to its rear end as we neared a traffic stop. I tapped the brakes but, of course, the snow caused the car to skid gently into the rear bumper of the sedan with a light “thunk.” I’d never been in a car “accident” before so I remained in the driver’s seat in shock, allowing the surreal to settle over me like a soft blanket of snow. My boyfriend, in the passenger seat, blurted, “Oh shit.”

I didn’t know what to do. Did people still get out and do the whole “exchange insurance info” for such a minor collision, if it could even be called that? Especially while it was practically blizzarding outside? A few seconds later, the question was answered when the driver got out of his car, tread carefully to the back of his vehicle to inspect his bumper, and then, swiveled around to peer into my snow laden windshield. I can’t be sure what he managed to see or what he thought he saw through the whizzing wipers, but it pissed him right off. He threw his hands up in the air before crashing them violently atop the hood of my car. He then stared menacingly through the windshield at me, daring me to get out.

I didn’t.

Instead, my boyfriend, stormed out of the car with a “Oh no you fucking didn’t!”

I watched the two men trade verbal jabs while the snow continued to land on their eyelashes, the lapels of their pea coats, their bare heads of hair. I couldn’t hear anything they were saying, but it didn’t matter. The noise around me dissolved into a low buzz, the way it often did right before I passed out. Only I didn’t pass out because the universe was shouting at me, had been shouting at me, the minute that man’s hands slammed against the hood of the car that I was was sitting in. And what was the universe shouting?

“You do not matter.”

The Parking Lot Feeling.

Growing up, I often felt this curious sense of unease any time I was too far from home, even if I was with my family. In fact, I still sometimes get reverberations of this feeling today, especially when Anthony and I are traveling. It’s like an echo of an echo, one that injects me with the immensity of all the empty spaces in the world. Sometimes I refer to it as “the parking lot feeling,” because of all the lonely and unfamiliar parking lots I hated seeing in college when I left the safety of campus, where I already felt so detached from those I loved.

I often write about the screen door of the Skokie house, which represents to me all the safe things inside our home–my grandmother’s command over the spaces in my life, her capacity to sweep me up into her strong arms and away from danger, the soft click click click of her teeth as she pulled the tails off mung beans while sucking on a piece of hard candy. Outside the screen door, however, lay all the perils of a world that didn’t know how to say my name, didn’t care to know what my name even was. Wide swathes of hearts too busy, too preoccupied, too heavy for empathy or even regard. Where cars could slide across a road slick with soft snow and collide into an endless reservoir of apathy, rage, disdain.

The world didn’t give a fuck about what was right or wrong. Instead, it allowed us to operate like ants on a hill, waging our little battles in rush hour traffic, without any thumb on the scale weighted towards justice, fairness, compassion, love. How else could I explain that a random man I didn’t know felt he had the license to direct such unbridled hostility towards me? I thus sat there in my car, belted to the driver’s seat, but unmoored in every other way, unraveling at the enormity of the world and the cruelty that filled it.

The next day, my heart turned off.

I don’t really know how else to describe it. I just stopped feeling anything for anyone. I didn’t love my boyfriend anymore. I didn’t even really care for my parents or my brother. At least, that’s what it felt like. Where once resided a hot, roiling bucket of thick emotions for those I cared about, now sat an empty, impenetrable tomb.

My worst fear was coming true. I was going to lose the love of my life, not because he came down with cancer or walked in front of a speeding bus.

But because I all of a sudden stopped having the capacity to love.

Or so I thought. It made no sense–how could I feel nothing for him or for anyone else, but be in such distress over this fact? If I really didn’t care about him or my parents, why would I care that I didn’t care, right? This is the logic puzzle that continued to tug and tug and tug at my sanity until one day, I woke up, walked over to my closet to get dressed for work, and collapsed into a puddle of clothes on the floor. I started to cry and wondered whether the only solution to this horrifying vacuum that had sucked up all my love and replaced it with a despicable abyss was to end it. End everything.

End me.

Omma found me like that, in my bedroom, unable to move. I didn’t know what to say to her, so I told her the truth.

“Omma, I don’t want to live anymore.”

And then, I leaned into her. And she held me the way she once did when I was a small child while I cried into the shallow alcove of her neck.

Afterwards, she got up, went downstairs, picked up the phone, called into the Emergency Room, and told them she was taking the day off. A few minutes later, she came back into my room, gently pulled me off the floor and walked me down to the living room, where a cup of hot tea waited for me on the coffee table. She sat me down and then nestled into the loveseat adjacent to me, tucked her cool hands between her knees before saying to me,

“Now, what’s the matter?”

Overcoming the Taboo of Mental Illness.

Mental illness is often thought of as a “secret” sickness, one that brings shame upon not just the individual suffering from the ailment, but their family, as well. This is particularly true in Asian families. According to one study, despite “high levels of depression symptoms,” there remains “low utilization of mental health services among Korean-Americans.” Why the apparent reluctance to treat mental illness? “[Korean Americans] tend not to seek help due to misconceptions of mental illness and treatment and the stigma attached to mental illness and treatment, as well as the lack of culturally and linguistically appropriate mental health services in the USA.” Dr. Geoffrey Liu, a psychiatrist at McLean Hospital, explained that in Asian culture: “Mental illness is seen—and I should emphasize, incorrectly—as taking away a person’s ability to care for others. For that reason, it’s seen as taking away someone’s identity or purpose. It’s the ultimate form of shame.”

This explains why I remained completely clueless about my aunt’s schizophrenia until I was in law school. Until then, she was just a little “kooky” in a somewhat endearing way. This also explains why my parents never once even thought about sending me to a mental healthcare professional during all those years in junior high or high school, even though evidence of my distress was literally carving up my arms like railroad tracks. But, they had no problem signing me up for a “guidance counselor,” one who was dedicated to helping me achieve the highest SAT score and getting me into the best college possible.

It wasn’t until I was required to see a therapist in college, upon threat of being kicked out of school, that my mother finally acquiesced and took me to a therapist. To her credit, she dutifully drove me to each appointment and never once made me feel ashamed about the process. I think that this introduction to mental health care, as something more than a treatment for alcoholics or drug addicts or the truly “insane,” was a critical component to my mother’s ultimate capacity to rescue me when I needed her most. Without this coerced exposure, I’m not sure Omma would have had the tools necessary to support me when I suffered my first real breakdown, one that was far more dangerous than the little flirtations I’d had during college.

And by tools, I mean simply the language necessary to fight off the urge to enshroud my depression within the muffled, padded walls of shame. Instead, she was able to treat the illness with the clinical objectivity of a healthcare professional, unclouded by judgment or bias, while lifting me up and out of the hole I found myself in with the sheer power of her love.

I know that by now, I’ve painted a motley portrait of my mother. Some areas might be dark, shaded, or hard to look at. Some parts of the picture may not make sense with others. Omma will always be the woman who birthed me, named me, loved me, and, perhaps, at times, hated me, or at the very least, hated the fact of me.

But of all things, to me, my mom will always be the woman who came into my room, joined me on the floor, held me in her arms…

And rescued me.

Ask Joanne

Hi Joanne. I’m a very emotional person. I laugh in serious or sad situations and very easy to upset or get angry about small stuff- stuff I think isn’t even worth getting upset over. And it’s very visible to others. Do you have any tips about not wearing your heart on your sleeve so much, or to be able at least to mask a emotion / reaction that is inappropriate during the moment? -Speckle

Speckle,

This quandary of yours is very relatable. I, too, have a tendency to wear my heart on my sleeve, and it’s gotten me into a right pickle a few times. I once wrote an entire blog post about how I would Google “how not to cry” because I was sick of how often I would burst into tears with zero advanced warning. I have a few thoughts, as well as some practical advice to curb your “inappropriate” reactions.

First, and you probably already know this, when your emotions are getting the better of you, it usually signals a much larger, underlying problem that is going unaddressed. For instance, I’ve noticed that when I’m particularly stressed over a big presentation at work or an upcoming long run, I tend to “get angry about small stuff.” This morning, I was running late from the gym and had about 40 minutes to get dressed and makeup ready for a large conference in which I was the keynote speaker. I pulled into the garage, got out of the car, and bulldozed my way to the door. But it was locked. And I nearly lost my freaking mind!!! My husband has a tendency to lock all the doors of our house for no reason–i.e., even when he’s home. Unfortunately, neither of us has a key to the garage door and therefore, I had to re-open the garage, walk out and around the front yard, and enter through the front door of our house, after which I had to go back to the garage to close the garage door. And even as I was still steaming at my husband’s door-locking compulsion (he was happily and obliviously sipping away at his espresso in the kitchen while I stormed up the stairs), I knew that I was getting angry over something quite silly and the reason for that was because I was really nervous about the upcoming speech I had barely practiced.

When you start noticing that you’re biting people’s heads off for small things, that you’re crying over spilled milk (literally), ask yourself, is there something going on in your life at that time that’s causing a bit more agitation than usual? Sometimes, it’ll take a little work to really get down to the nub of your anxiety and identify what’s actually causing you to lose control of your feelings in a way that’s making it hard for you to interact with others or simply function at all.

The key, of course, is having the wherewithal to step back and notice this about yourself. But, it sounds like, from a macro perspective, you’ve got that covered–otherwise, you wouldn’t be asking for the advice. However, it becomes much harder to see these things about yourself from a micro perspective, when your emotions are so “in your face” that it’s almost impossible to gain any perspective. Here, it might be helpful to jot down a list of words that describe how you act or what you do when you are “visibly” upset by “small stuff.” It could look like:

- Shut down and stop talking to people

- Hide in my room

- Play really loud music, even though it’s annoying

- Criticize my friends to make myself feel better

- Raise my voice or even yell at ppl I love

- Eat every ounce of ice cream in my house

- Pick fights with my partner

- Rage clean the house

- Cry in public

Forcing yourself to write some of these things down will help you identify these behaviors in the future, so that Rational Speckle can then say, “Oh, I’m doing that thing again, where I fly off the handle for small things. Let’s hit the pause button for a minute and see what’s really going on.” In the example with my husband and the locked garage door, I was able to say to myself, “Oh, I’m just stressed about the presentation” and then, I literally forgot about it until I read your question.

Finally, Speckle, I think it’s important for you to remember that you are who you are. When my dog Rudy died earlier this summer, I thought I was losing my mind with grief. I was surprised at the enormity of my sadness and when days turned into weeks turned into months, I turned to my husband and asked him, “Why won’t this feeling go away?” And he said something quite loving to me: “Babe, I’ve said this before, but you feel things so deeply. It’s your superpower. It’s what makes you so beautiful. But it’s also what makes this so hard.” While your emotions may sometimes get in the way, and there is certainly value to learning how to navigate the rollercoaster when that happens, you should also know that your capacity to feel things as deeply as you do is also what makes you so uniquely lovely. Inside the crucible of your feelings, you will develop empathy, compassion, emotional generosity, and, the courage to be vulnerable–as you have already demonstrated to all of us.

So, Speckle, don’t always be in such a hurry to stuff that heart back up your sleeve.

Wishing you all the best.

Updates/Random Things.

- GIVEAWAY WINNER!!! Thanks to all of you who entered the Cooking with the Spirit Giveaway!! Both winners have been notified by email so make sure to check your inbox to see if you won a signed copy of Tabitha Brown’s NYT Bestselling cookbook!

- What I’m Watching: Ok, so I caved and finally gave in: watched the first episode of House of the Dragon on HBOMax. Or, I watched about 20 minutes of it. I dunno. I just was NOT into it, and this is coming from a die hard GOT fan (well, up until the last season). I’ve read every book that George RR Martin has published and am pretty familiar with GOT lore, but I could not stomach another show with needless and purposeless violence, death, and betrayal. I don’t know if it’s me or the show or some combination thereof, but I’m not recommending House of the Dragon, particularly if you’re an animal lover.

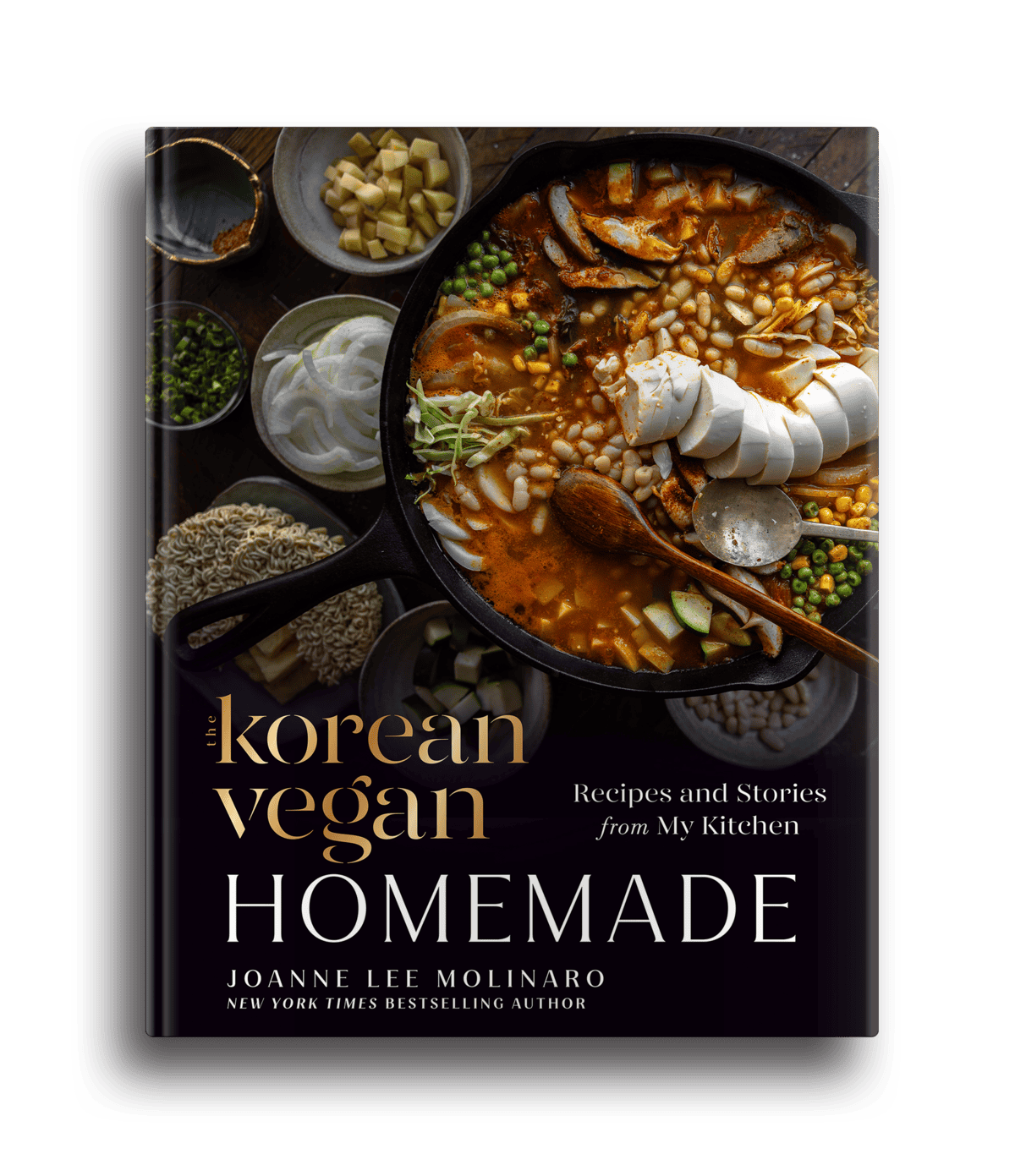

- Signed Copies of The Korean Vegan Cookbook: Last weekend I went to Now Serving LA–a bookstore that features only cookbooks–and signed their entire stock of The Korean Vegan Cookbook. It was such a great way to celebrate the books 1-year anniversary! If you’re interested in getting a head start on your holiday shopping, you can order your signed copy here for delivery!

- What I’m Cooking: This week, I cooked up what my husband calls one of the best pasta dishes he’s ever had, way better than anything he’d get at a restaurant. I know, I know, he’s biased, but, I’ll let you be the judge. Here’s the recipe for my take on Gigi Hadid’s VIRAL Vodka Pasta:

Vodka Gochujang Pasta

4 servings

½ lb rigatoni 1 tbsp extra virgin olive oil, plus more for garnish 2 tbsp finely diced shallot 3 cloves garlic, minced 1 tsp sea salt 1 tsp crushed red chili flakes ¼ cup tomato paste 2 tbsp gochujang 2 tbsp vodka 2 tbsp cashew cream (can sub in hummus or vegan sour cream) 2 tbsp grated vegan cheese, plus more for garnish Fresh basil, for garnish Cracked black pepper

1. Cook pasta according to package instructions, subject to the following: (a) reserve at least 1 cup of pasta water, and (b) cook for one minute less than the required time.

2. Once pasta water becomes nice and starchy, mix ½ cup with cashew cream and set aside. RESERVE another ½ cup pasta water.

3. While pasta is cooking, add 1 tbsp of EVOO to a large pan over medium high heat. Add the shallots, garlic, and salt to the pan, and cook until the shallots grow translucent (about 1 minute). Add the crushed red chili flakes and cook for about 30 more seconds, until fragrant.

4. Add the tomato paste and gochujang and stir until the vegetables are evenly coated. Deglaze the pan with vodka, scraping up all the brown bits at the bottom of the pan. Reduce heat to medium and then, stir in the cashew cream + pasta water mixture.

5. Add 2 tbsp of grated vegan cheese and continue stirring for about 1 minute, so that the sauce gets nice and thick.

6. Add the cooked (al dente) pasta directly to the pan with the sauce, mixing aggressively while adding more reserved pasta water as necessary if it gets too dry.

7. Season to taste and garnish with extra vegan cheese and fresh basil, as well as a little drizzle of EVOO and a crack of fresh black pepper before serving.

Parting Thoughts.

A few years ago, while sitting on the bench at 3rd and 40th in NYC waiting for the Jitney, a bus that would take us into the Hamptons, Anthony ran his index finger along the length of my left arm. “What are these? What happened here? I don’t think I’ve ever seen these before.” I had always assumed he’d seen them and just not asked. In retrospect, I should have known that his eyes sometimes have a tendency to slide past things like this. “Wait, you did this to yourself? Why?”

I started to say all the things I always say when people ask me about the scars along my arms:

“I was stupid.”

“I was young.”

“I was disturbed.”

None of which he accepts as real answers. There is a line forming, now, for the bus we are waiting to board. A mother and a daughter chat over their luggage. The mother is wearing khaki shorts and sandals, her daughter is in a white cotton blouse that slides off her narrow shoulders by design whenever she swishes her hair back and forth. From somewhere, a breeze moves through our little waiting area, as though prowling for the best place to land, and I wonder whether it ultimately perches on the girl’s bare shoulders.

“The pain on the outside helped to dull the pain they were causing me on the inside,” I finally manage to say.

And there it is again, that breeze. As if nudging closed a door that had remained open for far too long.

“Well, obviously, you’re right handed,” he says.

– Joanne