CAREER CHOICES: Was I Destined to be a Lawyer?

Read Ep. 17 | Show Notes

Subscribe Below to Receive the TKV Newsletter in Your Inbox

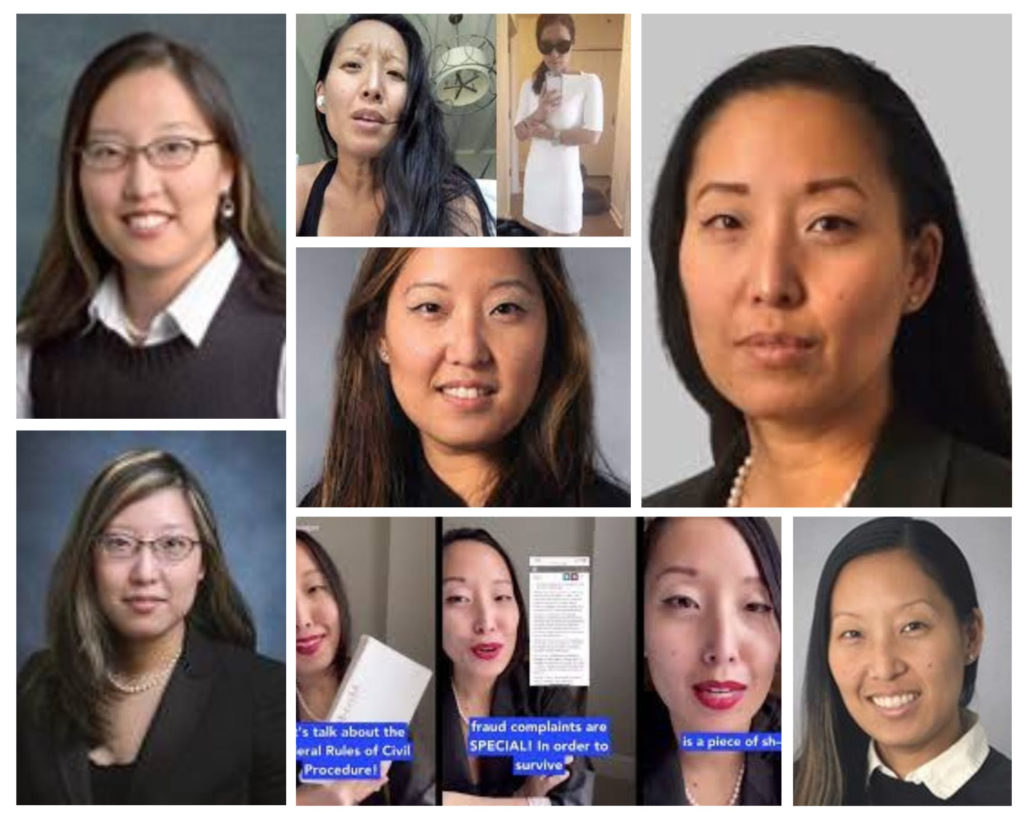

A few weeks into quarantine, the judge on my biggest case (at the time) ordered a video conference with only the attorneys, in preparation for an upcoming evidentiary hearing. I signed in a few minutes early–the judge’s seat was still vacant. His clerk, however, was at her desk and online. Before I had a chance to introduce myself to her, she said, “Ma’am, this conference is for attorneys only. Not witnesses.” As she was finishing up her admonition, the other attorneys came online.

All men.

All of whom heard the judge’s clerk dress me down for attending an “attorneys only” conference.

“I am an attorney,” I answered with a practiced smile.

Later that morning, the clerk sent me an email, apologizing for the gaffe.

It wasn’t the first time I’d been mistaken for a “non-lawyer,” but it was the first time since I’d made partner. I like to think that the exceedingly poor resolution of my webcam took several years off my face. But it did make me wonder, once more, whether she’d have made the same mistake with a man (she obviously did not subject any of the men who joined the conference to the same “warning”). Even if the answer to that question were “yes,” the damage was already done. Not only had she required me to affirmatively assert my right to be in that space–literally–she did so in front of my peers and opposing counsel.

In many ways, my career as a woman of color in Big Law can be summed up by repeating the following phrase over and over and over:

I deserve to be here.

I am not one of those persons who went into law because I’d always dreamt of being a lawyer. Quite the opposite. I always swore to my parents that I would never be a lawyer, out of spite. My mom often taunted me with, “You should be a lawyer,” whenever I talked back (which was pretty much all the time), to which I would reply, “NEVER!!”

But here we are. I’ve been a practicing lawyer for over 18 years, now.

As with going vegan, there isn’t one single thing that caused me to pursue a career in law. Most immediately, though, it was the anxiety of being an adult. I graduated college a year early with no job and only the vaguest notion of a plan. I was still living with my parents, but the future pressed down on me, made me feel small and helpless, and so I did what everyone was doing at the time–picked up a copy of the local paper (the Chicago Tribune) and scoured the classifieds for the word “writer” (I had a degree in English). Within a few months, I landed a job as a resume writer: I wrote CVs for executives and other professionals who had been laid off or divested from large companies. In some ways, this was a great job to have right out of college: it forced me to scrutinize hundreds of career paths in corporate America.

One morning, I flipped open the folder sitting atop the large stack of manilla files weighing on my desk. Inside was a 1-page resume for a lawyer in trust and estates. Not my typical assignment, and maybe that’s why it stuck out to me. I’d never had to craft a CV for a lawyer before. She listed her salary as $45,000 a year, and I remember thinking to myself, “Not bad.” Based upon the home economics class I took in high school, $45,000 would be enough to pay rent, buy a car, insurance, and still have some left over for annual vacations to California. I googled “how to become a lawyer,” and upon learning of the incredibly structured journey towards gainful employment, quickly decided that a career in law was for me. Like medicine, you went to school for a few years and usually had a job before you even graduated. But unlike medicine, there was no blood involved (I faint at the sight of blood).

The “lockstep” rhythm of a career in Big Law was in stark contrast to the forest of decision trees an MBA candidate would be forced to trek through. In short, there were too many things a person could do with an MBA (or not do, I guess), whereas, with a JD (Juris Doctor), you have far fewer choices. And at that time in my life–when I was staring down what felt like the Goliath of life choices–the fewer options I had, the safer I felt. So, I signed up for the LSAT, took a weekend prep course, applied to only two law schools, and got into both. I felt like a million bucks (even though I could barely afford the application process–resume writers don’t make much). I was finally taking one solid step towards adulthood, one that my parents could be proud of, and thus one I could be proud of.

On the first day of law school orientation, Dean Levmore spread his arms out as if trying to embrace our entire 178 person class in a bear hug, saying, “Getting here,” he pointed at the lectern, “was the hard part.” Maybe because it was so much easier to believe him, I relaxed in my seat, sat back and watched the long straight line of Easy Street unfurl in front of me towards the chalkboard, where someone had scrawled the words “Welcome Law Students!”

It turns out that “getting there” was the easiest part.

I learned pretty quickly that being a woman meant I’d have to say, “I am the lawyer” (literally) more often than I expected. As a first year associate, I remember covering a motion hearing in Lake County up in Waukegan, Illinois. Suburban courthouses are often much nicer and more updated than their urban counterparts (Cook County lives up to its name as “Circus Court”), but because they are farther away (and clients are less likely to pay for the time it takes to get to them), I was never very familiar with their layouts. I managed to get through security without a hitch, but once I retrieved my briefcase off the conveyer belt, I discovered that this beautiful glass-ceilinged facility did not organize their courtrooms in a logical manner. Not wanting to be late to my hearing, I made a beeline for the friendly looking “Information Hub” at the center of what appeared to be a large atrium.

“Excuse me,” I said quietly to the woman sitting at the desk. “Do you know where I can find Judge Nolan’s courtroom?”

“Where’s your attorney, honey,” she asked.

Taken aback, I answered, “Oh. I am the attorney.” I could feel my entire face turning red, as if somehow it was my fault that this woman assumed I was not an attorney.

A few weeks later, when I could make my way to Judge Nolan’s courtroom with my eyes closed, I presented a motion for summary judgment against an opposing counsel who never bothered to answer my requests to admit (if you’re a lawyer, you know how dangerous that is). The judge entered a briefing schedule and adjourned. As I was walking out through the double doors, opposing counsel gestured towards the back end of the corridor. I followed him, not entirely surprised. I’d just filed a motion that would sink his entire case. But, I was already prepared to tell him to pound sand, even if I had to do so after the courtesy of hearing him out.

What I didn’t expect was his reaction when I told him, “No, I’m not going to withdraw my motion.” He was much taller than me–by at least one foot–I remember his shadow trying to swallow my entire body as he crossed over to me, so that we were standing only inches apart. He placed his hand on my shoulder, bent over to peer directly into my face and quite literally simpered,

“What’s wrong?”

Because of course there had to be something wrong with me for filing a motion that was a direct consequence of his dereliction.

I stepped about a foot back. Pulled his hand off my shoulder with just my thumb and index finger, as if I were picking off a snotty handkerchief, and let it drop somewhere in the–now considerably larger–space between us.

“What’s wrong is that you didn’t file responses to my requests to admit within 30 days,” I answered, sniffing rather indecorously as I took yet another large step backwards. The slimly looking grin disappeared, replaced by a grim, pinched up line. He stepped towards me again, but not to ingratiate. To intimidate.

His voice–slick and sweet not seconds before–was now cold and sneering: “You’ll never win your motion. Judges up here don’t grant motions like that, however late you are with your responses. Good luck,” he practically shouted, before turning on his heel and heading back into the courtroom.

He was right. The judge didn’t grant my motion. He did, however, make him pay my fees in connection with arguing the motion, saying that opposing counsel had “wasted [my] time.”

I was still a first-year associate when I learned that being an Asian attorney was also going to be a “thing.” I was sitting in a partner’s office who thought it was totally cool to ask me “why do you people [i.e., Korean people] do that?” while talking about his fascination with Asian women. A few years later, as a mid-level associate, I was working late on a brief. The partner stopped by to say goodnight on her way out. She started singing a tune (she really loved Broadway musicals), one I’d never heard before. I must have had a puzzled expression on my face, because she asked, “What, you’ve never heard this before?” I shook my head. She shook hers. And then said,

“God. You’re so Korean.”

I laughed, because that is the deferential (and politically expedient) thing to do when your boss (and all partners are our bosses when we are associates) makes a joke at your expense. But inside, it was like someone had punched me in the stomach and all the air in my lungs rushed out in a sort of wheeze that I hoped passed for something that sounded like polite laughter.

There wasn’t really a word back then for these types of things. These little “incidents” are today, I guess, referred to as “micro-aggressions,” something that everyone now gets training on as part of diversity and inclusion initiatives. But, at the time, it was just another reminder that however much I tried to play the part, however hard I worked to earn my spot, I would never really be “one of them.” It wasn’t malicious. My colleagues, for the most part, loved me (and I loved them–even the one who told me I was too Korean). They didn’t intentionally try to make me feel like I didn’t belong, which is probably why I often just rolled my eyes, ducked my head, and did the work. But, all those little paper cuts, over time, can turn into big wounds if they continue to go unaddressed. And after years and years of thinking “it’s not a big deal,” you will be totally unprepared for what happens when micro morphs into MACRO.

Someone once asked me how to find your passion. I gave them the only answer I knew: figure out what makes you madder than anything in the world. The opposite of that is your passion. I hate injustice. And, to me, racism is among the most unjust things that exists. At the risk of psychoanalyzing myself in public, I will confess that my “passion” for racial justice is, in part, selfish. The world is full of evil–John Wayne Gacy, Jeffrey Dahmer, Jack the Ripper. But these are serial killers, anomalies in human evolution, a species that requires compassion and empathy in order to survive. While they’re scary, their “scare quotient” is vague, kind of like being afraid of ghosts or monsters. But, the fact that racism–one of the great sins of humanity–is practiced by not just a handful of defective human beings, but by large swathes of the global population–terrifies me. It demonstrates a profound imbalance in the world, and as a result, I feel like I’m walking on a tightrope with no safety net, all the time. The prevalence of racism means that at any moment, someone can strike me, knock me off my balance, and hurt me in a way that will reveal that however many rules and laws and morals and ethics gird our humanity, we are, at bottom, vessels of chaos and destruction.

I hate racism for the same reason I hate driving in the snow: it makes me anxious. It threatens to unravel me every second of every day, and therefore, I don’t know how not to fight it every second of every day.

Thus, when I saw two white men lynching a young black jogger in Georgia, everything inside my head became still. A few months later, when I witnessed a white police officer squeezing the life out of a black man on the streets of Minneapolis, the world grew muffled, as if someone had wrapped a towel around my ears. On the outside, everything was obnoxiously loud. Rage decanted and splashed across the streets because some pains have no purpose other than to be expressed. But inside my head, it was so quiet. Too quiet. It wasn’t just the fact that these things were still happening. It was that they were done openly, on camera–indisputable evidence that too many people believed that the color of your skin could determine how much you deserved to live.

As I’ve talked about before, I went on autopilot at work. I could sense, though, a latent anxiety. It was like someone had plucked the fattest string of a bass guitar right inside my stomach and I was doing everything I could to keep my body from vibrating with it. I cut out all caffeine, billed from my dining table from sunup to sundown, moved my cases forward through a new legal landscape with zoom backgrounds and cross-examinations defended through my iPhone while shod in house slippers. When I had time, I took photos of the protests around my neighborhood, read essays on police violence, examined the problem of Racism as if trying to untie a knot with my bare hands. In some ways, the fact that the world outside had exploded in rage was soothing to me–somewhere, people were feeling what I couldn’t afford to as I continued to inch my way forward on the tightrope.

A few weeks after being told to leave an “attorneys only conference,” my partner and I scheduled a settlement call with opposing counsel. I’ve had my fair share of contentious cases. This one landed fairly close to “red hot” on the toxicity scale. Lead counsel on the other side seemed to derive great pleasure at skirting the line of professionalism, often injecting “arguments” aimed at us personally, instead of just sticking to the law. He also had, in my opinion, a nasty and discourteous habit of failing to provide us with notice and withheld crucial information until the last minute (i.e., while we were in court), all designed to make us look like idiots in front of the judge while giving us almost no time to effectively respond. Thus, I had little hope that we would resolve our differences on the settlement conference, but agreed to give it a good college try.

My partner and I hopped onto the call with lead counsel for the other side and his colleague. Three men and me. After we exchanged a few obligatory niceties, we got down to brass tacks. I stayed quiet most of the time, answering a few questions here and there, letting my partner do most of the talking. But, as I predicted, we were going nowhere fast, and at one point, opposing counsel asked with unvarnished derision seeping through the phone line, “Why do you have to fight everything?” By this time, I’d had it up to here with the amount of bullshit posturing and simply decided to tell him exactly what was on my mind:

“Perhaps if you had the courtesy to give us a little notice before filing things–“

But I didn’t get to finish what I was saying, because he bowled right over me, shouting “OH THAT’S FUCKING BULLSHIT LINDA AND YOU KNOW THAT IS.”

Something about the way he called me “Linda”–the name of one of our co-counsel, a totally different woman from a totally different law firm who had a really pronounced southern accent and sounded nothing like me and was never introduced as even being on the call–it snapped the guitar string inside of me with an ugly twang. I was NOT going to be made invisible again.

I interrupted him right back and yelled straight into my phone:

“THIS IS JOANNE MOLINARO AND I’M NOT DONE TALKING YET.”

As soon as I got off the phone, my husband, who overheard my side of the conversation from the kitchen, commented, “Wow babe. Very sexy.” But I didn’t feel sexy or fierce or empowered. I felt completely depleted while still shaking with rage. I stared at the phone, still in my hands, and all I could think was, “How are we still fighting over something so stupid when black people are dying for being black?” Hearing this self-important asshole call me Linda, all the tiny little attempts at invisible-izing me were just reminders of a much larger, much more horrible machine that was literally erasing people before our eyes ON TELEVISION. And for the first time in my entire career, the idea of walking into work where the overwhelming majority of faces would look totally different from mine was unbearable. All those years of having to smile politely, laugh at slightly racist jokes, tolerate having my credentials questioned when my peers were automatically admitted, they came at me like an avalanche.

So, I fell off the tightrope.

And crashed.

Ten months later, I was still working from my dining table. I took a quick break from work emails to scroll through my newsfeed.

“ATLANTA SHOOTING: 8 KILLED AT ASIAN SPAS IN GEORGIA, SUSPECT ARRESTED.”

“Six of the eight victims were Asian women.”

“Yong Ae Yue”

“Soon Chung Park”

“Suncha Kim”

…

I stopped reading.

These names sounded way too much like my mother’s.

Once more, a weird stillness settled over me. And I went back to work. That night, in bed, I caught up on the day’s events, rereading the names of all the victims: Yong Ae Yue, Soon Chung Park, Suncha Kim, Hyun Jung Grant, Xiaojie “Emily” Tan, Daoyou Feng, Delania Yaun, Paul Michels. I stared at the picture of the young man who murdered all these people, feeling nothing other than an empty sort of curiosity: how does a “sex addiction” translate into murdering a bunch of Asian women? It soon became evident that, to this man, unsanctioned sexual attraction equalled sexual attraction to Asian women, and therefore, he had to erase the source of his unsuitable fixation–something that was only made possible because of the repeated dehumanization that occurs when a human feature (like a woman’s ethnicity) is fetishized.

I processed all of this like data on a spreadsheet. I hooked my phone up to a charger and set it on my night stand. I shut my eyes. “I should feel something. Why don’t I feel something? This is not good.” The following day, I logged back into work, sitting at the same spot at my dining table as I had through virtually all of quarantine. I kept a tab open to keep an eye on additional coverage on the shootings. In the afternoon, I tuned into the press conference held by the city of Atlanta. Captain Jay Baker, a spokesperson for the Sheriff’s Office, stepped to the podium. A paunchy man with deep set eyes and a pate so bereft of hair that you could see the glare from the studio lights reflecting off of it. With one hand resting on a sheet of paper and the other waving around in front of him, an officer dressed in full uniform, the Sheriff’s star twinkling from his right breast, looked straight at the camera as he described the murderer of women whose names stilled rolled around in my mouth with far too much familiarity:

“He was pretty much fed up and kind of at the end of his rope. Yesterday was a really bad day for him and this is what he did.”

“Yesterday was a really bad day for him…”

And just like that, the string snapped.

I was NOT going to sit there and let another white man throw an invisibility cloak over Asian women. I was NOT going to allow anyone to throw that same cloak over my rage. I was going to reveal my pain and fear and anger and put my name–Joanne Lee Molinaro–all over it, forcing the likes of one Captain Jay Baker to see me, to feel, for one second, as powerless as those women felt as they were slaughtered by a deranged man who saw Asian women as expendable, as impotent as he tried to make me feel by rendering our repeated dehumanization and ultimate brutalization as merely the exclamation point of a white man’s “bad day.”

A couple weeks later, I drafted a memo for the entire firm. I told everyone what it was like being an invisible woman among them, forced to hide my Koreanness lest another partner tell me I was “too Korean.” I told them that my heart was broken by the Atlanta shootings and that there were days when the idea of showing up to work was suffocating. I told them all these things after 17 years of saying nothing at all.

And then, I signed my name to it.

Joanne Lee Molinaro.

I said earlier that there were a lot of reasons I became a lawyer. I don’t think it was as accidental as it may seem. While there was definitely a “process of elimination” that went into my career choice, it wasn’t just my anxiety that drove me to pick a job that offered structure and financial security. Even as my mother yelled at me for talking back, there was a small, hard kernel in me that was proud of the fact that I talked back, likely planted there by none other than my very opinionated, very ferocious mother. Something clicked in a very satisfying way when I finally concluded that I would go to law school, almost as if I’d finally latched onto the path that had always been meant for me.

I say this now, even as I’ve obviously shifted away from my legal practice to a very different kind of career. But, I learned so much about effective storytelling as a trial lawyer, about leveraging my strengths instead of copying others to get what I needed for my clients. When I started sharing stories on The Korean Vegan, I wanted to make sure that my family’s stories, i.e., the immigrant story, was seen. I did this specifically because I knew, first hand, what it felt like to be invisible, to have to show up day-in and day-out to a place where yours was the only Asian face, yours was the only Asian name. I knew, also, that bullying people into agreeing with you was almost never effective; rather, you had to open their hearts with a compelling story, one that humanized those that would otherwise be too easy to keep de-humanized. And finally, I learned that keeping myself invisible so as “not to rock the boat,” to avoid blowback from my employer, to make sure I stayed on that tightrope without tipping over–

It was overrated.

A Chat With Arden Cho On Partner Track.

As you may have seen on my Instagram, a couple weeks ago, I had a chance to chat and cook with the talented Ms. Arden Cho, the star of the new hit Netflix binge-fest, Partner Track. This eminently addictive new show features a Korean American lawyer working at a large law firm in NYC. It was totally triggering and healing at the same time for me! You can check out my entire interview with Arden on this week’s podcast!

Updates/Random Things (Show Notes)

- Upcoming Live Event: I’ll be doing a LIVE event at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign (my alma mater!) on September 23!! Make sure to secure your spots NOW!!!

- What I’m Watching: In addition to Partner Track, I’ve watched about a billion TV shows while recuperating from COVID (still testing + as of the writing of this newsletter, folks). I fell hook, line, and sinker for Only Murders in the Building, which is so funny, so well written, so beautifully crafted, I ended up watching it and then starting both seasons all over from the beginning right after finishing the Season 2 finale (to watch with Anthony). I also watched a haunting movie recommended to me by none other than my 4-year old nephew, called My Octopus Teacher, which, incidentally, picked up the Oscar for Best Documentary in 2020. A stunningly shot and beautifully told story about a man’s friendship with a wild common octopus. Make sure to have tissues handy for this one!

- What I’m Talking About: In case you missed it, I had a WONDERFUL time chatting with my friend Berto on his podcast, the Berto Calkins Podcast. We talk about content creation, running, dealing with injuries, and friendship. Make sure to check it out!

- What I’m Reading: Did you read this AWESOME article in Eater about the popularity of Asian vegetarian/vegan cookbook authors? So proud of this line up and EXCITED about the fall’s lineup of cookbooks!!

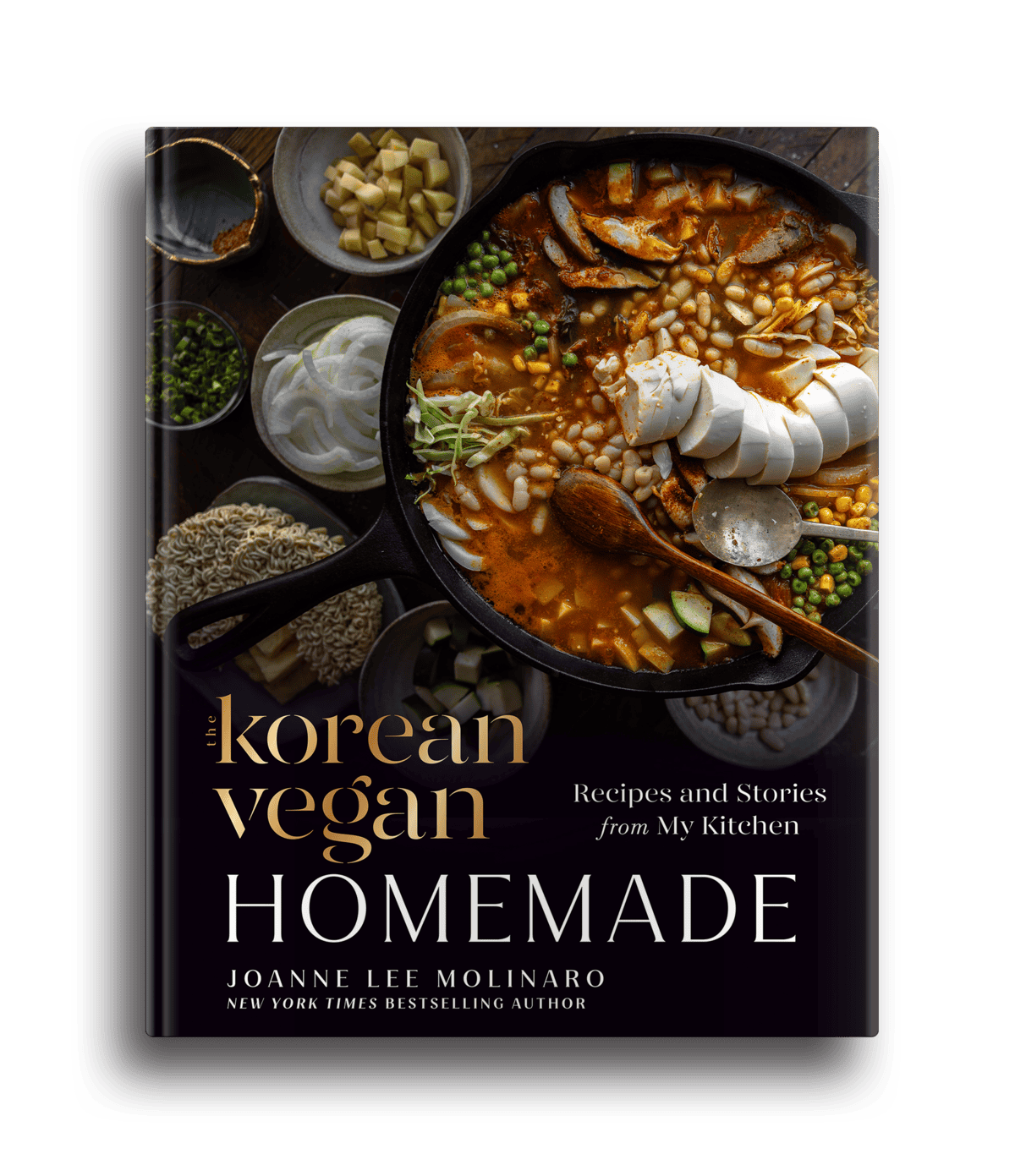

- International Editions of The Korean Vegan: I am BEYOND excited to announce that The Korean Vegan Cookbook will be published in several different languages this fall!! You can check them out here!

Parting Thoughts.

Several years ago, on my way into the office one morning, I passed a mother and her daughter walking out of the hotel (my building is adjacent to the Westin). They reminded me, so much, of me and my mom. Although what conversation I could overhear was in Chinese (and thus incomprehensible to me), I imagined that, like me and my mom, they were discussing the elusive, but beckoning “future.”

She (the daughter) looked to be in her early 20s. Taller than her mother (by a few inches), she strode confidently ahead towards Dearborn, while her mother took dainty steps behind her. Her skin was perfect, her outfit on point (a small black jacket with brass zippers, leggings, and booties), and her black hair framed a face carrying the kind of ease that befits a 20-something with the world ostensibly at her booted feet. Her mother was styled more comfortably in a navy blue fleece, jeans, and sneakers, her hair short and tucked neatly behind her ears.

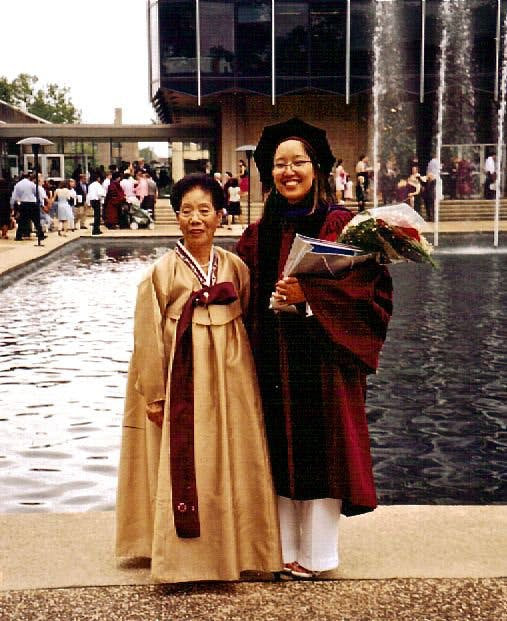

For whatever reason, seeing them took me back to a scene right out of the Green Lounge of my alma mater. At that time, though, the ability to call the place my “alma mater” was nothing but a pipe dream. I was there merely to sit for the LSATs–the prerequisite exam to even apply to law schools. I had only just shared my intention to try for law school with my parents a few weeks earlier. Some of the secrecy had been grounded in the fact that I didn’t want to hear the “I told you so” in my mom’s voice when she discovered I’d given into her repeated “encouragement” to go for a career in law. The other part of it was that I didn’t think I could shoulder their disappointment if I failed.

The risk of failure was imminent–I had three weeks to prepare for my LSATs and the two schools I applied to (I refused to leave Chicago) accepted students with only the highest GPAs and LSAT scores. So, I saved money from work to cover the fees associated with the LSATs and even put some aside to take a crash weekend course to help me prepare for the test. But, it’s hard to keep things like these a secret when you’re living with your parents, and soon enough, my mom was like, “Uh, what’s up with all these books and stuff?” And so, I sat there, on my mom’s peach leather sofa while she tucked her hands between her knees and listened, without interruption, to my halting and somewhat disorganized “plan” for my future in law.

Her reaction was pitch perfect:

“If you don’t get into these two schools, don’t bother going to law school at all.” My mom had 100% perfect attendance at the school of hard knocks, and though she had mastered the fine art of bullshit to a tee, she rarely employed it with her firstborn. She always knew how to dig up the kernel of fear that I cocooned with rationalizations and “protocols” and “processes,” and toss it back at me, so that it landed right at my feet. I retorted that her apparent lack of “faith” in me was precisely why I didn’t want to tell her at all.

But, Omma came through, as she always does. She paid for a portion of the weekend course I’d signed up for and offered to drive me to the LSAT testing site–all the way in Hyde Park.

Which is what brought us to the Green Lounge at 7:30 in the morning, hours before the exam was scheduled to start. We wandered into the huge hall, bedecked with comfy velvet sofas and dozens of square tables, shafts of sunlight as thick as tree trunks cutting through the quiet from the floor to ceiling windows throughout. Soothing artwork in greens and lavenders hung with a silent sort of dignity on the walls, complementing the resident member of the Cow Parade that lazed right in front of the Northern windows.

We settled into a couple of chairs and as she sat down, my mother whispered,

“Wouldn’t it be great if you went to school here?”

I laughed. I was nervous and jittery (from excess coffee) and basically terrified that I would make some sort of misstep in this “rest of my life” blueprint.

“Uh, yeah, that would be great,” I whispered back, staring out beyond the Cow into the fountain out front.

I didn’t know then that the Cow, the cheery fountain, the “melatonic” paintings, and even the colorful chairs we were sitting in–that all of these things would become as second nature to me as chewing my fingernails while waiting to take the test that would decide my future. That one day, I would be walking towards my downtown office, a partner at a large law firm, watching a mother and daughter disappear around the corner of Dearborn and Kinzie.

That years later, I would be sitting at my kitchen table, thinking back on that mother and daughter and the bend in the road they couldn’t yet see as they stepped into the heart of a city engorged with the sun.

Best,

– Joanne