What Does Family Mean to You?

Receive the TKV Newsletter in Your Inbox Every Tuesday!

Last week, we talked with Dr. Robynne Chutkan, a leading gastroenterologist and 4-time author on the microbiome. In case you missed it, you can check it out here. Although I knew Dr. Chutkan would fill my plate with TONS of info, I was surprised at how inspired I was by her passion for health and wellness. In particular, I was moved by the following answer she gave when I asked what it means to “be well”:

“It’s definitely not just the absence of disease. It is how we feel mentally. It is our outlook. Do we feel optimistic? Do we feel happy? …. And I think a big part of it is, do we feel empowered? Do we feel like we have it within our control to influence what’s going to happen to us?”

Too often, we view “health” as interchangeable with the size of our waistband, how fast we can run a mile, or whether we’re on any medication. What I love about Dr. Chutkan’s definition of “well” is that it focuses not on the absence of bad things, but on the presence of good things–primarily, agency.

Dr. Chutkan asks some big questions:

Do we feel optimistic?

Do we feel happy?

Do we feel empowered?

Do we feel in control?

This week, I wanted to investigate one of the primary drivers of optimism, happiness, empowerment, and control:

Family.

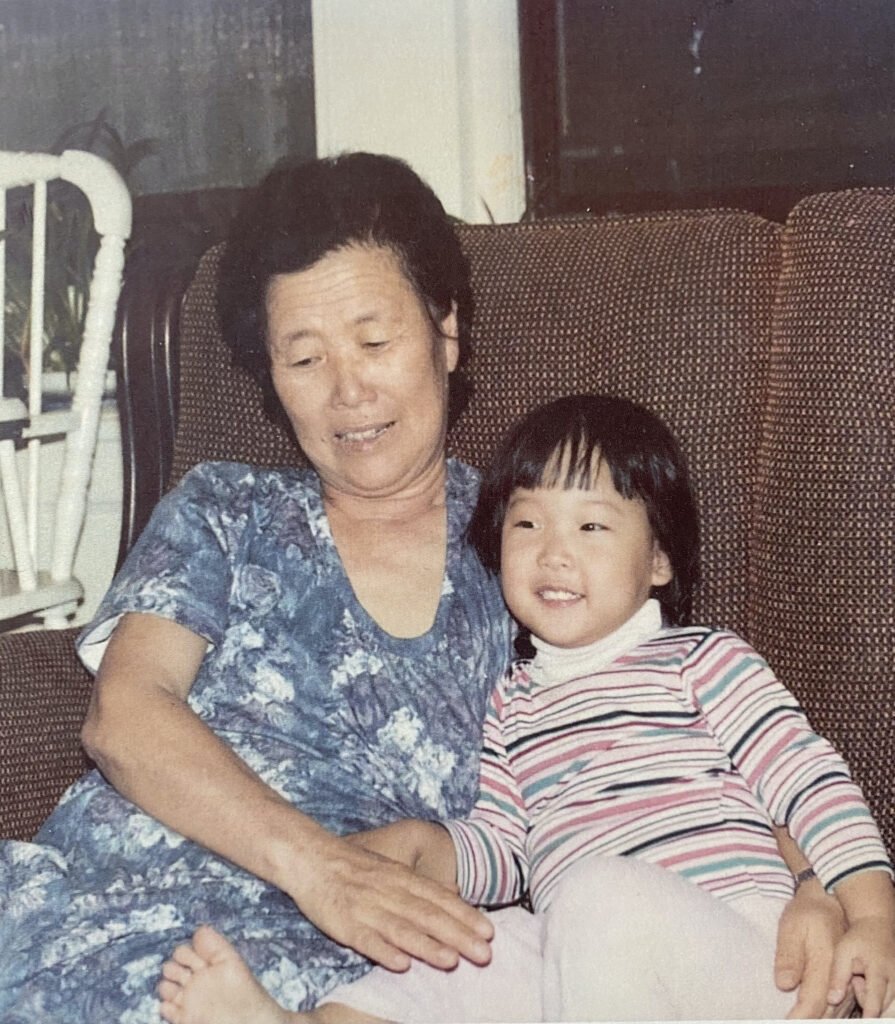

“Sunyoung-ah! Jaesun! Get up!! Eat breakfast!,” my grandmother hollered from the kitchen.

Hahlmuhnee always woke up with the sun. I imagine she began her day by praying because Hahlmuhnee liked to bookend her days with a brief (sometimes not so brief) chat with God. She would then saunter on down to the kitchen, her slippered feet whispering across the thick carpeting that lined practically every inch of our Skokie house, except for the kitchen itself–that room was a page right out of a 1970s nightmare, complete with tacky linoleum tiles, dark wooden cabinets, and an orange ceiling light that basked the space in a sticky, lurid glow.

“Click, click, click” the stovetop would greet her, as she reached for the non-stick skillet that her daughter-in-law purchased at Venture earlier that summer. This was the best pan she’d ever used–the eggs never stuck. The dooboo always flipped. The jeon was always crispy. “Click, click, click,” the stovetop repeated, as she turned the dial to a second burner. She was never anything but amazed that she now lived in a home with a stovetop that had five–FIVE!–burners.

She placed a small pot on the stove filled with water and two sausages (or “hot dogs” as her granddaughter called them), then cracked an egg over the skillet, watching the edges bubble and grow opaque with a loud, satisfying sizzle.

“Sunyoung-ah! GET UP!!,” she bellowed once more. Her son was still finishing up his shift at work and her daughter-in-law had already left for the hospital. She didn’t approve of such a lopsided schedule–one parent working at night, the other during the day: the family was rarely together as one unit. But the kids were still young, the parents young, too. There was time enough for all that, she supposed, and she could hardly complain–they lived in a house where everyone had their own bedroom, a five-burner stovetop, and vents that breathed frigid air into each room during the hot summer nights of Chicago, a feat of engineering that she couldn’t have imagined in her wildest dreams as a young mother in North Korea.

She plated the fried egg–cooked hard, the only way I would eat it–along with a hot dog. She then poured a tall glass of milk, because no granddaughter of hers was going to suffer from calcium deficiency. She sucked in a breath, ready to call for me again, when I tumbled into the kitchen like a half-inflated beach ball.

“Eat. Everything,” Hahlmuhnee said, biting off the words in a way that forestalled any argument.

This was a typical morning for me, growing up. My parents weren’t home, but Hahlmuhnee always was. She would make breakfast for me, braid my hair, then walk me to the bus-stop, wave goodbye (until I was too old and told her she didn’t need to anymore), wave hello when I got back from school, walk me home, fix me a quick after school snack, watch some Sesame Street with me, teach me how to swing at the park, make fun of me for being terrified of cicadas, yell at me until I brushed my teeth, and then tuck into bed with me and tell me stories about the girl with a fairy hahlmunnee, or the two sisters and the tiger, or the boy who lived inside a big peach until I was fast asleep.

I recently watched an absolutely BEAUTIFUL vlog by an artist named Jackie Liu. In it, she asks several of her friends–those she includes in her “chosen” family–the following provocative question:

What does family mean to you?

As I watched each of Jackie’s chosen-family members piece together definitions of the F-word, I inevitably struggled to come up with my own. I kept circling back to the idea of “unconditional love,” but that only led me to query whether something truly “unconditional” could exist. For instance, my ex-husband was, at one point, a “family” member and yet my love for him was decidedly conditional, failing to outlast my favorite yellow Dutch oven. And although the most illegal thing I’ve ever done was to pirate a rental copy of Best of the Best from Blockbuster Video, it was theoretically possible that I could do something so heinous and criminal, my own parents would disown me.

Still, the idea of mostly unconditional love (I know, that’s pretty much an oxymoron, but you get my drift) and the safety provided by the most expansive boundaries of love and acceptance one could imagine–this, to me, was one of the defining qualities of “family.” But perhaps this is an incomplete definition, since not all of us are born into “unconditional love” and therefore may not inherit (at least at first) all the benefits that flow from that sort of singular stability.

Indeed, according to one study, to what degree a child experiences unconditional love, can have a direct impact on the likelihood of developing, in some cases, significant mental illnesses. According to a 2015 study appearing in Europe’s Journal of Psychology, a child bereft of Unconditional Positive Regard–a term the study used to refer to a child being consistently prized regardless of one’s behavior, as well as constant affection and acceptance–was significantly more likely to develop agoraphobia, anxiety, depression, and neuroticism. In contrast:

“Individuals whose parents demonstrated support, affection and responsiveness to their needs most of the time tend to be less sensitive to rejection . . . . [and] more inclined to see themselves as more competent and likeable.”

While one cannot overstate the importance of unconditional love (or “regard”) in a young person’s development, it would also be myopic to suggest that every child receives the kind of “support, affect and responsiveness” from their parents that best equips them for all the ups and downs that life throws at them. Are parents automatically included in the term “family” by virtue of their biological role in creation, regardless of their parenting skills?

I can empathize with those who would opt to define family exclusively by choice. The traditional definition of family is far too narrow and rigid, failing to make room for the kind of families that thrive when choice is part of the formula.

But when the definition of family turns exclusively on choice, according to this study published by the MDPI, “something crucial is missed, both in terms of understanding and analyzing contemporary society . . . . [M]any people believe themselves to be under weighty familial duties that do not result directly from their own choices.” For instance, many young adults feel obligated to care for their senior parents, even if they don’t have the best relationships with them. Because they are “family.” Similarly, you may have recently attended the funeral services of that uncle you saw maybe 4 times in your entire life. Why? Because he’s “family.” There are also legal implications that are definitely not elective–child support, alimony, and insurance are just a few of the levers that courts can use to enforce an institutionalized definition of “family.” Irrespective of whether these values or laws comport with the idea of unconditional love, they are real and thus have real consequences.

The authors of the above study provide a potential alternative to defining family:

“Family scholars should be less interested in defining what a family is and more focused on what families do . . . .”

More specifically, “[f]amily must … be (i) enacted, (ii) displayed, and (iii) recognized.”

This definition of what a family does leads me directly to this week’s Ask Joanne. Ahn asks the following:

“Do you believe that children must give their love to their parents unconditionally, even if lasting pain has been inflicted?”

No.

There is no per se mandate–legal, social, or emotional–that requires you to engage with your parents. The concept “But they’re family!” is also not dispositive, not in my book, at least. As discussed above, we should be concerned far more with what families do in lieu of focusing exclusively on what a family is. In this way, individuals–particularly those who have been subjected to neglect, abuse, or even violence by their “families”–can free themselves from whatever social constructs or normative ideals that have placed them squarely within the crosshairs of adults who, quite frankly, have no business rearing future adults.

In other words, Ahn, my hope is that one day, you will be in a position where you get to decide how much or how little you want to expose yourself to these people who created you. You get to decide just how much weight, if any, you want to grant the term “biological parent.” You get to decide whether the two people who were tasked with raising you irretrievably squandered that honor.

Does that mean you shouldn’t give unconditional love to your parents? That really depends on how you define “unconditional love.”

You see, there’s always a cost. You may lose their financial support (which, for some, might be significant), even if you never had their emotional support. You may realize that whatever small sliver of affection you received from them was extremely valuable to you (you know the saying “You don’t know what you have until you lose it….”). But indisputably, the most costly consequence of your choice vis-a-vis your parents is opportunity.

The choices you make today will have a direct impact upon the opportunities that await you in the future. You can choose to invest in your relationship with your parents or you can choose to cut your losses and walk away. If you do the latter, you may be forever foreclosing on the kind of parent-child relationship you’ve always wanted.

I didn’t always have the best relationship with my parents. My mother once walked out on us, declaring she wasn’t our mother anymore. My father kicked me out of the house at 13 because I refused to make instant ramyun noodles for my little brother. I realize these are relatively minor infractions compared to cases of domestic violence or serious neglect, but I wouldn’t put my parents up in the “Mom & Dad Hall of Fame.” Still, at no point in my life did I ever consider retracting my love for, and subsequently, my sense of obligation to, my parents. Part of this I attribute to that seemingly innate craving for my mother’s love–a craving that at least one study likens to an opiate addiction. And perhaps it was that craving that led me to believe, unquestioningly, in the possibility that at some point, I could forgive them and we could build something worthwhile together. Maybe not soon. But at some point.

[In the case of the instant ramyun incident, it was later that night when my father started sobbing “SORRY!”]

But investments are tricky. Just look at Bitcoin! Our vision is necessarily hampered by a lack of information, misinformation, and, of course, confirmation bias. We want to believe what we want to believe and that craving for maternal love can create a formidable bias.

But not all investments are as volatile as Bitcoin. Mutual funds are a solid bet, even if you invest a little bit here and there. Here’s the thing: you can still do things for your parents–pick up their groceries, help them fill their prescriptions, translate their bank statements–even if you don’t love them, so long as doing so doesn’t cause more injury. Not “because they’re family,” but because of your hope that they might one day tell you the story about the boy who lived inside a giant peach and earn a permanent seat at the table inside your heart.

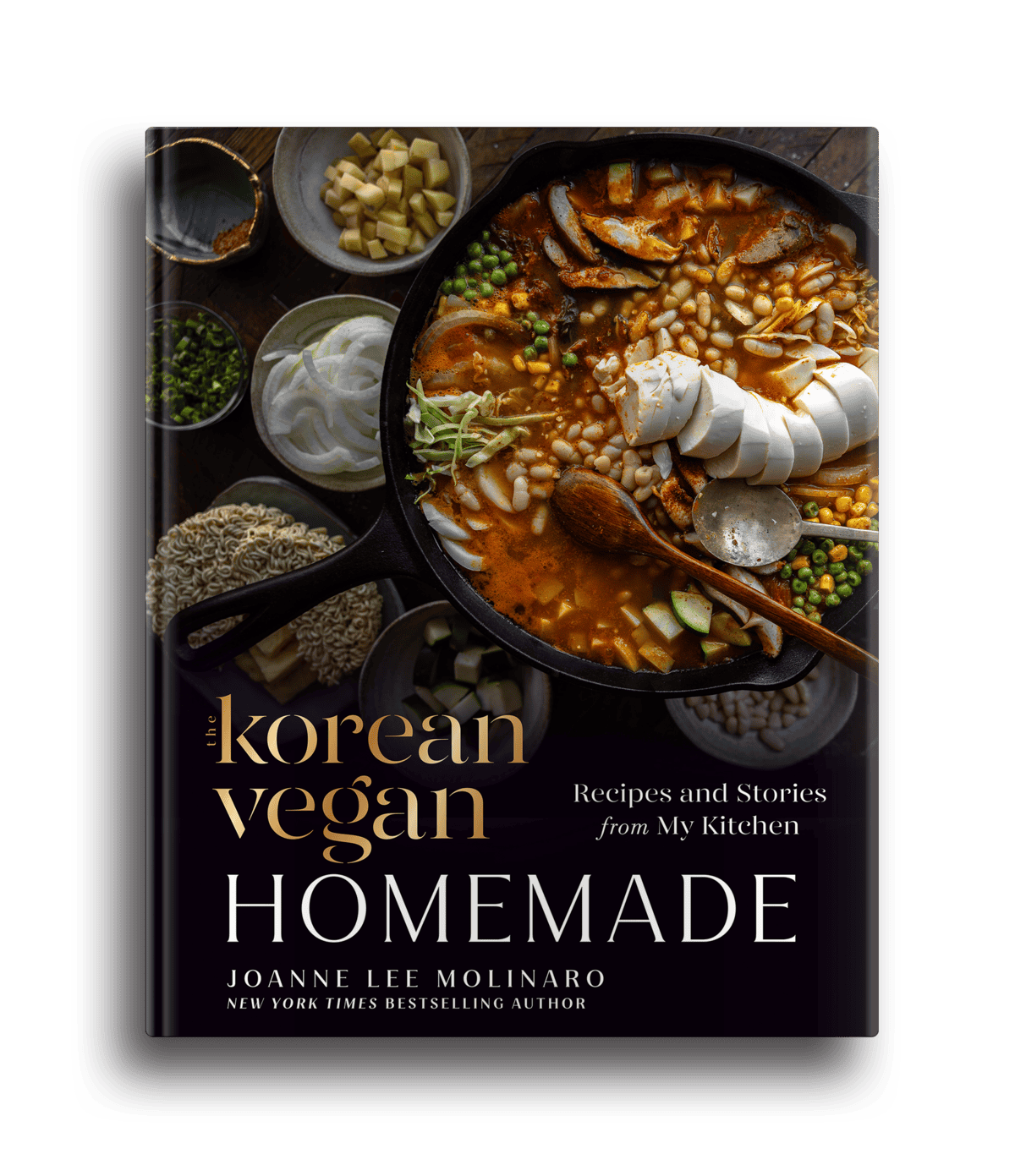

This Week’s Recipe Inspo.

Spice Up Your Life.

Spicy Ramen Salt

A spicy, umami packed blend of seasonings that’ll enrich your broths, pop your popcorn, and heat up your pasta sauce!

What I’m…

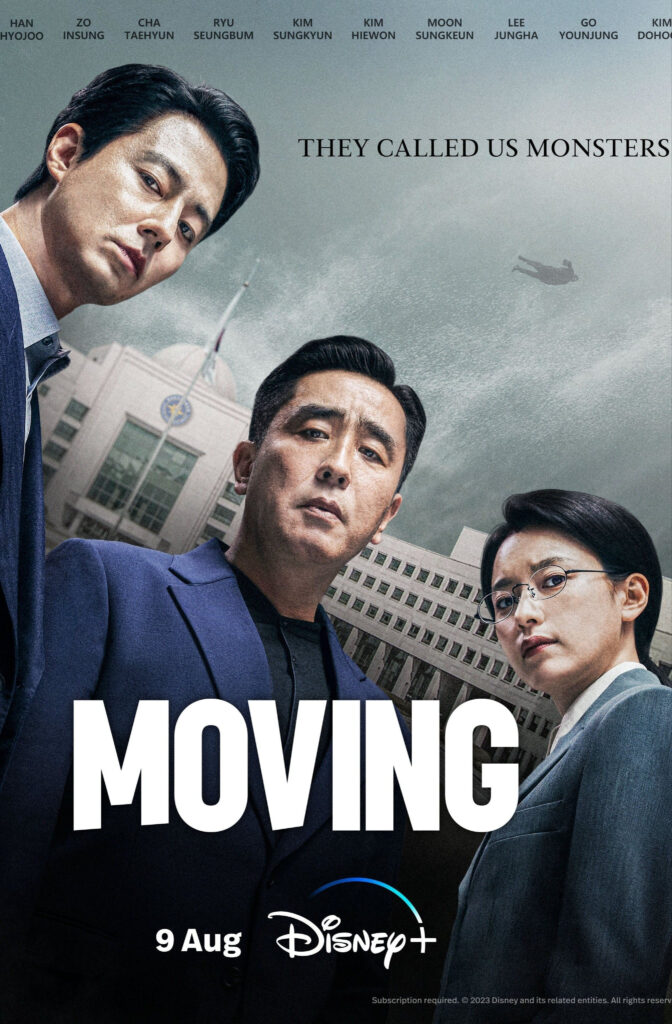

Watching. I know I featured this K-Drama last week, but I’m re-featuring it because it is THAT good. Full of heart, excellent writing, and beautiful cinematography, this one is the REAL DEAL! Can’t wait for the full season to wrap later this month! Watch –>

Reading. I tore through Karin Slaughter’s Will Trent series and was patiently awaiting Book 11. I just started it this morning and so far, I’m loving it. If you enjoy a great serial on serials, then I highly recommend Slaughter’s books (and no, I don’t know if that’s a pen-name….!). Read –>

Wearing. I’ve moved away from lash extensions (they’re kind of annoying) and gone back to a solid mascara–particularly Elf’s Lash n Roll. It makes my lashes look longer and curlier! I also love that Elf is reliably vegan and cruelty free! Shop –>

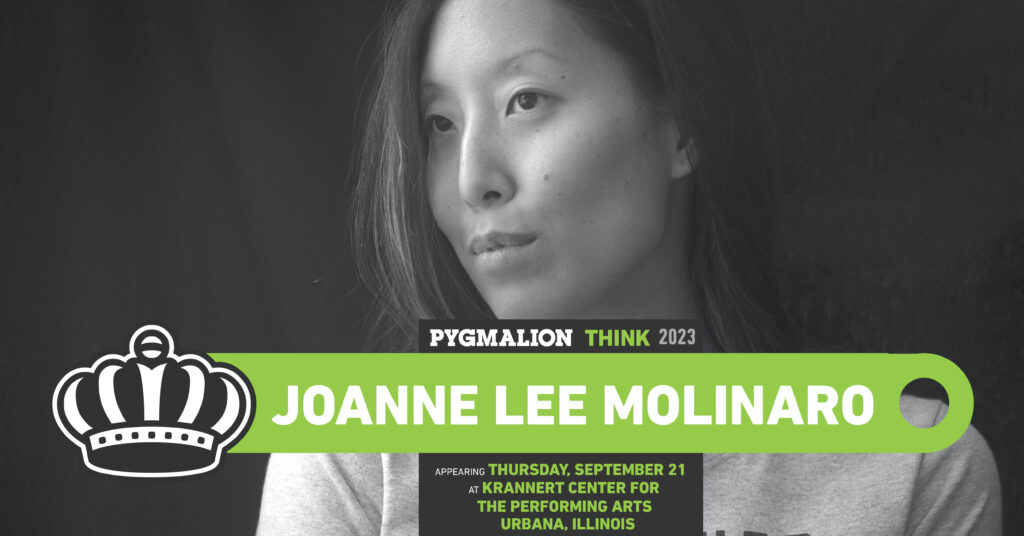

Book Signing:

Urbana-Champaign, Illinois.

I’ll be headed back to my alma-mater, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign next month on September 21 to do a LIVE cooking demonstration and book signing as part of Pygmalion Think 2023!! Make sure to pick up your tickets and come say hi!

Parting Thoughts.

“Family” often starts, in our minds, with the person who gave you life. Every couple of days, Omma will send me a text complaining about the heat in Chicago and asking after Lulu, as if our little rescue dog is the granddaughter she’ll never have (at least from me!).

My father texts me a lot more than I would expect from a 79-year-old man. Earlier today, I received a message thanking me for sending him a chair. Omma followed that up with a photo of him in the chair. Yup, I’ve gotten to that point in my life where I now buy furniture for my parents. Last summer, my father helped me put together one of those swinging egg chairs that are really popular. We keep it in our backyard, where my father often likes to sit in the evenings when visiting, listening to music and swinging lazily inside the cocoon he helped put together.

I know that our parents comprise the family we didn’t get to choose. And for many people…. that hasn’t always been a good thing. But for me, it has been a wonderful thing…to see my parents moving inside a warbling purple dusk, moving towards each other, towards me, and sometimes outwards, but always moving in this one life, in this our love, in this, my family.

My Seoul Hahlmuhnee was always so proud of how many children she had and then even more proud of how many children they had. I sometimes dream about her, looking down through the thick leaves of a persimmon tree, still counting to see how many seeds have sprouted. I want to holler up at her,

“Hahlmuhnee, they’ve grown so beautifully.”

-Joanne