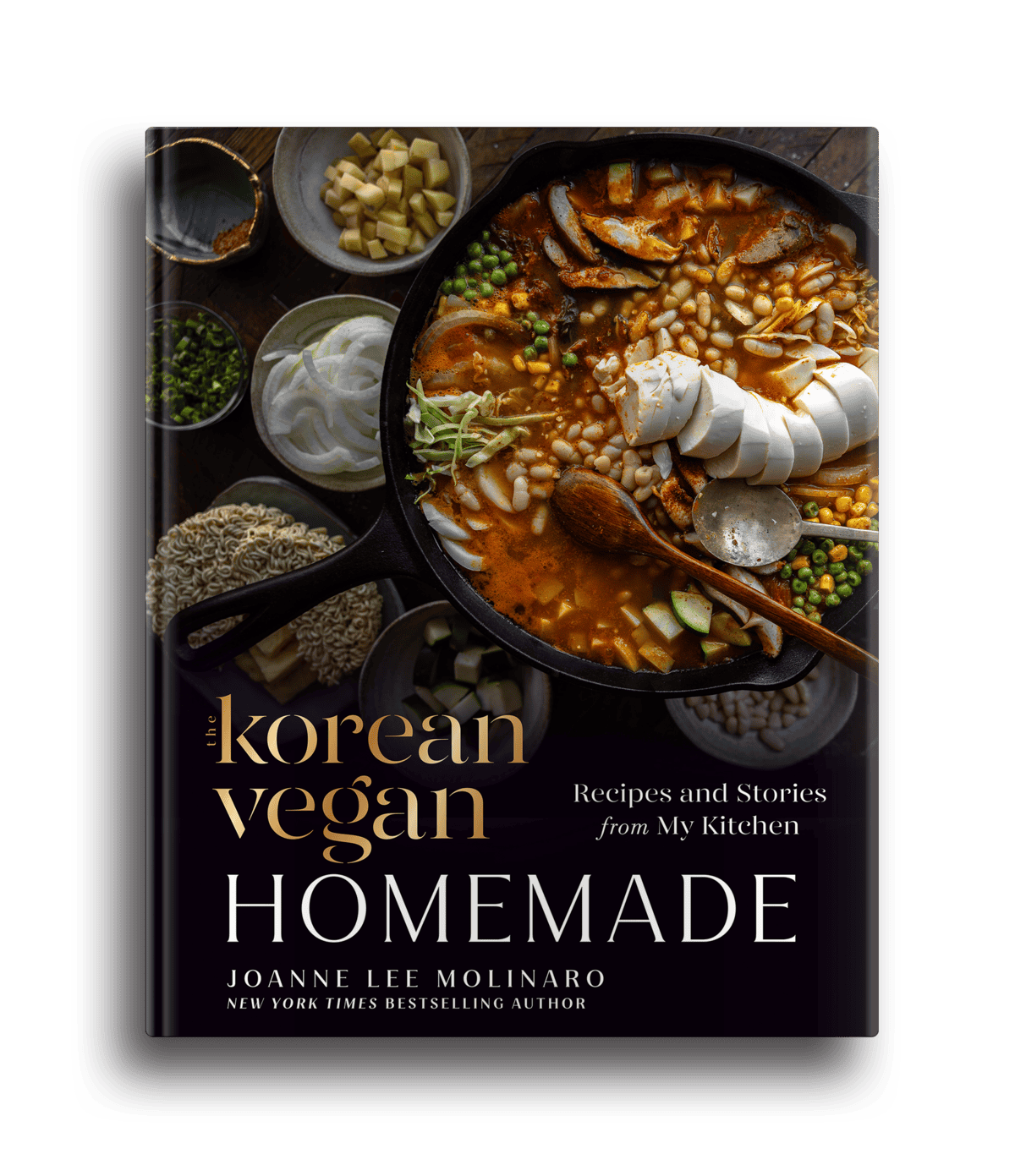

The Comparison Game.

Read Ep. 20 | Show Notes

Subscribe Below to Receive the TKV Newsletter in Your Inbox

There are 2 Types of People in Life…

Every year, right after partners receive their year-end compensation, the Firm releases a spreadsheet to all the partners identifying the exact amount each partner was paid. I never open it.

My friend Geoff, on the other hand, looks forward to this day every year like it’s some sort of holiday. A pristine, white envelope with the word “CONFIDENTIAL” in red print gets delivered to his mailbox and, in what seems to have become a yearly ritual, he tears it open, places the stapled spreadsheet on his desk, and spends the morning enjoying his 1 liter thermos of coffee while analyzing the rise and fall of his colleagues. Afterwards, like clockwork, he comes by my office, slides the door closed after stepping in, sits down at one of the two chairs I always keep available for these types of “drop-ins,” and launches into a brief summary of his thoughts on how well each of our partners fared (or didn’t) right before I put my hands over my ears and yell “I don’t want to know, I don’t want to know, I don’t want to know!!”

Which type of person are you?

Geoff or me?

My Mom’s Obsession with Jennifer Kim.

When I was ten years old, my parents decided to move out of our Skokie house and upgrade to a two story home in Wilmette, Illinois. To my horror, this meant that I would not be going to junior high with my best friends and, instead, would be enrolling at Wilmette Junior High School, where I knew not a soul. On the first day of school, I met a Jennifer Kim at the bus stop. Jennifer lived just down the street and around the corner from us. She was also Korean American, she was also starting 6th grade, and thus ensued the comparison game.

Within a few months,

“You know, Jennifer is studying to go to medical school,” or

“Jennifer is taking after school classes to help with her grades,” or

“Jennifer doesn’t do theater or acting, only orchestra.”

By the time I was in high school, the comments became more overt:

“Why can’t you study as hard as Jennifer?”

“Why don’t you take AP Bio like Jennifer?

“Why can’t you just be more like Jennifer?”

I remember once I exploded at my mother with,

“Maybe you should just be Jennifer’s mom!?!”

I didn’t take AP Bio, go to medical school, or quit theater. But, by the time I graduated high school, I had a firmly entrenched habit of measuring myself against those around me–particularly Korean American women. I am a competitive person by nature and I hate to lose. My father often made my brother and me play tennis during the summers and fall and too often, I walked off the tennis court carrying a newly disfigured racquet. Competition wasn’t fun for me. I hated playing tennis because it made me angry, left me feeling inadequate or distinctly “loser-ish.” Therefore, despite the uncontrollable act of sizing up everyone around me, I usually elected not to play with them at all.

In college, I majored in English, when virtually everyone else I knew pursued a degree in Education, Nursing, Business, or Engineering. Now, this was definitely because I loved to read and write, but it was also a little soothing to know that I would be studying a subject that few of my peers would be. In law school, only a couple of my classmates were Asian Americans, and as a practicing attorney, I was the only Korean American in my office for most of my career. On the one hand, this ensured that there were very few people who looked like me against whom I’d have to compete (and possibly lose). On the other hand, it was an inadvertent but still self-inflicted form of isolation, one I made efforts to overcome later in my career. While I limited my exposure to those who might challenge my fragile self-worth, I simultaneously kept my distance from those who could readily empathize with me.

Don’t get me wrong–the drive to excel continued to push me throughout law school and Big Law. During my summer internship with the Firm, I made sure to take on more projects, bill more hours, and stay later than my peers to ensure that the name “Joanne Lee” stood out when it came time to make full time offers. Similarly, when I started working at the Firm, I enjoyed–and worked hard to maintain–my status as the “go-to” litigation associate of my class, even if it meant that some of my peers viewed me as an irritating brown-noser.

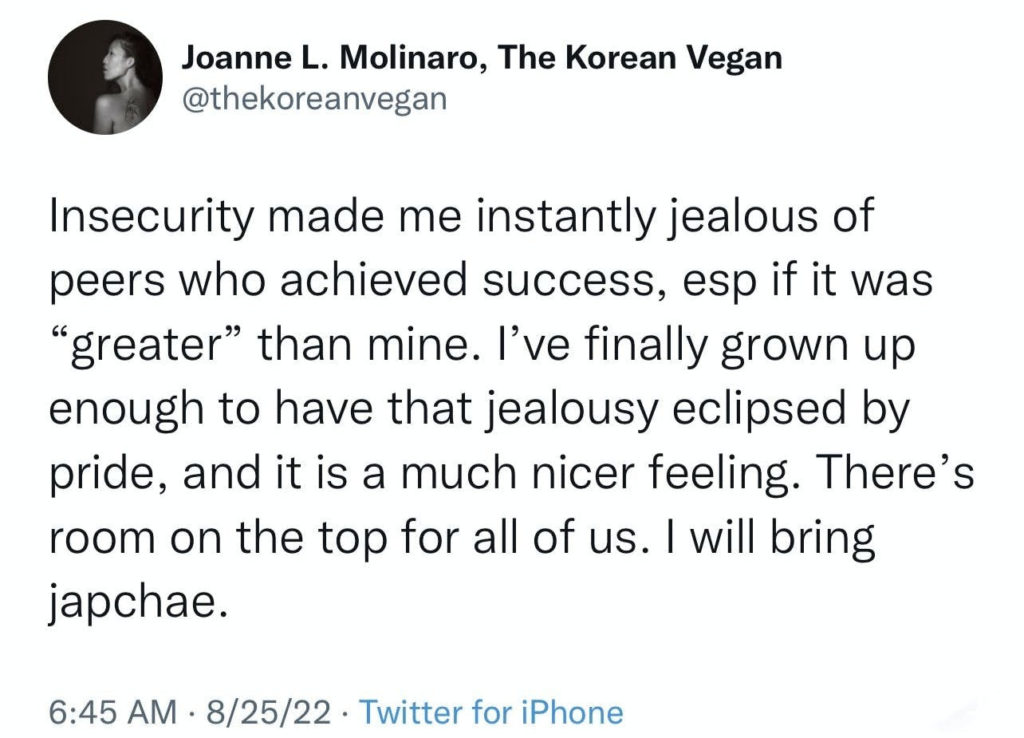

Jealousy Ruins Everything.

I have an instinct to reveal the ugliest, most embarrassing things about myself, largely to avoid having to do the work involved with hiding them from the world. There’s a great scene in My Mister (slight SPOILER alert) where the young female protagonist confides that sometimes, she’d rather just tell everyone that she once killed someone, because then, she would no longer have to live with the constant fear of them finding out. I share some of these less attractive aspects of myself out of curiosity and, let’s be honest, hope that I’m not the only one who experiences these feelings.

I often wondered if my peers at work looked at me the same way I looked at them: friends, for sure, but also, pieces to topple over on my way to the top. I hated how quickly I could dehumanize colleagues I considered to be my friends in order to soothe my self-esteem. But, I also assumed that many of them felt the same way I did. Of course, I never confessed this to any of them.

When I started creating TikTok videos in 2020, I made a rule to follow every single Korean content creator I came across on my FYP. This was directly a result of the isolation I felt in my legal career. The pendulum had swung and now I wanted to be surrounded by other Korean Americans, to have Konglish dripping into my ears at random intervals, to see people eating kimchi and rice with chopsticks instead of forks, to be reminded of all the things that made me feel safe when I was growing up. At first, it was everything I’d been missing during the earlier two decades. People began calling me “Unni” and “Noonah” (the Korean honorifics for “older sister”), something I hadn’t heard in years, and Korean Americans were actually proud of me. They wanted to claim me as one of them, and I happily accepted all invitations to the community I longed to be a part of.

And then, of course…

Jennifer Kim came up on my FYP (my TikTok feed).

Ok, not literally Jennifer Kim (though that wouldn’t be too far-fetched when it comes to how TikTok can seemingly read my mind). Rather, I started to see other Korean American content creators–several of them creating food content–who were experiencing dynamic success, oftentimes eclipsing my own. And while a part of me was super excited to see more Korean representation, there was a not-insubstantial part of me that resented their success, that wanted to hoard it all for myself, that felt overwhelmingly threatened by everyone who might take so much as a rice kernel out of the bowl I wanted to keep all to myself.

Just like that, creating videos and content became really not fun. Hopping onto TikTok was no longer the diversion from anxiety it once was, but instead, grew to be the source of my anxiety. I went so far as to block certain creators whose content was delightful but still triggering because of how many millions of views they racked up compared to me.

I told you. The “ugliest, most embarrassing things”….

Their success indicted me. Accused me of not working hard enough, not being smart enough, not being talented enough.

Not being enough.

Is This Inter-Generational Trauma?

I am not a fan of what I view as a rampant tendency for over-diagnosis in today’s pop psychology, and therefore try to use psychological terms carefully. I’ve learned a lot of new words and phrases over the past 5 years (e.g., gaslighting, virtue signaling, etc.), and “generational trauma” or “inter-generational trauma” was new to me, as well. According to the APA Dictionary of Psychology, “inter-generational trauma” can be described as follows:

“A phenomenon in which the descendants of a person who has experienced a terrifying event show adverse emotional and behavioral reactions to the event that are similar to those of the person himself or herself. These reactions vary by generation but often include shame, increased anxiety and guilt, a heightened sense of vulnerability and helplessness, low self-esteem, depression, suicidality, substance abuse, dissociation, hypervigilance, intrusive thoughts, difficulty with relationships and attachment to others, difficulty in regulating aggression, and extreme reactivity to stress.”

My parents are children of war. My father was born at the conclusion of World War II and my mother was born at the beginning of the Korean War. I’ve shared many of their stories in the past, but I will share two here that I believe shaped my parents’ narratives in ways they lacked the tools to articulate:

My great grandmother killed herself in front of her son, my paternal grandfather, when he was only 9 or 10 years old. He was shortly shipped off to boarding school, where he subsequently suffered a nervous breakdown. Not surprisingly, the loss of his mother at such a young age and under such tragic circumstances had a profound impact upon how he raised his own son. My father shared with me that when he was still quite young, his father doled out a “severe penalty” (my father’s word for “punishment”–something he picked up from watching lots of soccer) for lying:

“One day my father gave me a penalty as severe as could be for my lying to him. I didn’t even understand what the lie was and why he was so mad at me. He gave me no food for three days. I was sitting on the corner of the room all three days. After three days he gave me food but my appetite was gone and I was so weak that I couldn’t feel like eating.

I barely swallowed a little food and heard my mother crying over me and shouting,

‘you are going to kill your son.‘

I still don’t know what I did wrong to him even now.“

My mother once shared with me what it was like growing up during the Korean War. After my mother’s family fled North Korea, my grandfather was soon conscripted by the ROK military, leaving my grandmother, my mother, and her older sister alone. Every day, my grandmother would bring her two daughters to the open graveyards littered across war torn villages. Hahlmuhnee scoured the bodies in the squalid heat. She turned them over, touched their ghoulish faces, lifted their eyelids to check for a grey halo around the left iris.

My grandfather was blind in the left eye.

Omma, tied snugly to my grandmother’s back, buried her nose in her mother’s neck, as Hahlmuhnee sauntered over to each pile of bodies. My mother doesn’t remember the bodies, but she remembers the smell of war.

Because my parents grew up in scarcity, they related to the world from a position of dearth. From where I sit, I have the luxury of pursuing things like purpose, joy, fulfillment; but, for my parents, mere survival was the objective. The ability to hoard food and money meant the difference between living and dying for not just a few days, but for decades.

My jealousy of other content creators was causing me so much distress, I started to see a therapist about it. With a little work, I discovered that at bottom, the anxiety was actually a low-grade manifestation of fear. I was scared that my inability to keep up with the “Jennifer Kims” of TikTok would not only spell doom for a career and business in digital media and writing (which was terrifying since I’d just left a lucrative practice in law), but that it would render me a burden and unloveable to the people around me.

I know what you’re thinking:

For the love of GOD, grow a pair.

LOL.

I am by no means suggesting that the travails of my TikTok journey are in any way comparable to the kinds of things my parents suffered in their early lives. However, I can’t help but think that the latent urgency that hung around the dinner table each night might have fed me an extra LARGE dose of fear, one that conditioned me to believe that there was never enough for everyone, but especially for a Korean woman, and if I didn’t always stay one giant step ahead of the pack, if I didn’t hoard all the views, likes, followers to myself, if I wasn’t downright stingy with achievement and all other proxies of wealth, I might one day starve to death.

Literally.

Or, worse yet, I might become a burden to the parents who’d already been burdened with so much.

Being a “recipient” of intergenerational trauma doesn’t necessarily need to be a crisis. Sometimes, I think we’ve tricked ourselves into believing that every bad thing that happens to us needs to be a big, earth shattering event that requires years of therapy, endless analysis, and gratuitous self-victimization. It’s that tendency that you had when you were little—when you’d fall down and skin your knee, yet only start crying if your mom showed up to ask you “what happened?” If she hadn’t shown up, you’d probably have brushed off the dirt, gotten back on your bike, and rode it around the block until the sun started to sink and Hahlmuhnee called you back home from the screen door. While some things definitely merit the work that therapy entails, some things just require a little self-awareness. For me, knowing that my toxic jealousy is born out of a conditioned scarcity mentality gives me the language I need to walk myself back from my own distress.

This is called effective living.

Running with the Varsity Squad.

Notwithstanding the number of times my mother nearly died before the age of 10 (from infanticide and starvation), she describes her childhood the same way many of us would: “The persimmon blossoms fell and covered the ground like snow. I picked them off the floor and I ate them. They tasted sweet and pretty. I thought I was getting pretty. Like the flowers, after eating them.” She told me how much she loved picking blackberries along the mountain ridge that hovered over her home, digging up and munching on raw sweet potatoes or a bit of starchy arrowroot, making ramen noodles over a campfire when she lived in a tent with her father.

Similarly, my dad recounts that despite the hardship of having a mentally ill father, growing up in poverty, and constantly being afraid that he might not have enough to eat, “our life was enjoyable and not so bad as others thought usually. We were so young that we didn’t know what the poverty really meant. Neighbors were as poor as we were. We were simply happy to play all different kinds of games with friends in the neighborhood. We used to play soccer, baseball, handball, using the empty place or somebody’s large front ground. Sometimes we used empty spaces between the old tombs.”

In 2018, I became a member of DWRunning, a Chicago based running team. I can still remember when I first approached the head coach, Dan Walters, about joining. It was a Wednesday morning or “Workout Wednesday” and I decided to accompany Anthony, who was already on the team, to the Montrose Track on Chicago’s lakefront. We arrived early, an hour or so before the sun had emerged from behind “Cricket” hill. Dan was silhouetted against the coming dawn, the strap of his stopwatch swinging wildly beneath his elbow as he hollered times out to his runners. The inside of the track–a carpet of thick green grass–was littered with gym bags, water bottles, sweat pants, and hoodies. I even saw what looked to be a half eaten PB&J sandwich in a ziplock bag.

Working out on the track with semi-elite runners is like trying to merge onto the freeway in a small, beat-up car that hasn’t seen an oil change in over a decade. There was a lot of “stop and go” before my foot finally hit the rubber, and on that first day, when it did, runners zipped past me on either side within seconds. I slowly angled myself towards the outermost lane, but even then, I couldn’t escape the crescendo of thudding footsteps as one group of runners after another threatened to overtake me every 20 yards or so. I’d stare at their lean backs, marvel at the ease with which they loped past me, and, of course, feel painfully self-conscious about getting in their way.

Afterwards, while Anthony chatted with his teammates, I approached Dan on slightly wobbly legs. “So, do you coach only fast runners?” I asked, and suddenly, I felt like I was in junior high asking Isaac Kim, “Will you be my boyfriend?” But Dan was far more welcoming than Isaac. His face broke into an easy smile. “I train runners at all levels.”

I’ve been working with Dan, now, for four years. I’ve run 4 marathons under his guidance. In 2018, my first year, I set a PR (personal record) in every single race I ran, including a training run (i.e., the 2018 Chicago Marathon, which I used as practice for the Indy Monumental Marathon later that fall). I am the second slowest runner on my team (one that includes numerous Boston qualifiers and a handful of Olympic Trials qualifiers too), but I don’t really care. By 2021, I was regularly showing up to Wednesday morning track workouts, and more often than not, my teammates would huff a “Hey Joanne” as they raced past me. I looked up to them, calling them the “Varsity Squad,” knowing that I’d never ever be as fast as them, but still feeling like one of them. On race days, many of the faster runners who’d finished hours before me would stick around and cheer for me with my coach and Anthony, and I swear to God, seeing the faces of the Varsity Squad, their hands cupping their mouths as they hollered “GO JOANNE” while running towards a finish line–it was better than seeing fucking Barack Obama on the sidelines.

I don’t care that I’m the second slowest runner on my team. I don’t care if I’m nowhere near the front of the pack when I run a race. It’s fun if I place somewhere in the top 50%, but half the time, I don’t even check. I’m just happy to finish. I have my own set of goals that I work towards, ones that are thoughtful and reasonable, based upon where I am in my fitness journey and in life. Nothing pleases me more than meeting those goals, irrespective of where I place.

I know why I can adopt this mentality in running, when I have so much trouble doing so elsewhere in life: because I don’t run for a living. Whether I place 1st or last has zero impact on my bottom line. But the resilience my parents exhibited in overcoming their trauma is not unlike the toughness one must develop to run a marathon. More importantly, that powerful surge of electricity that shoots through your body when you see your teammates screaming your name at Mile 18 reminds you that even if there isn’t yet room enough at the top for everyone, if you pull them all up with you, you’ll have the capacity to build room when you get there.

Together.

Ask Joanne

Hi Joanne, for my question, my mum bought me some tofu to put in with my instant noodles, and I’d like your opinion on how to cook it best. Fyi, I tend to put spinach on the bottom, then my noodles, then my spring onions in the bowl. I pour boiling water over it, then cover it with a plate until cooked. Or if I have fried vegetables, I put those on the top. What do you think the best way to cook my tofu would be? -Anya

Hey Anya! Fellow instant noodle fan here! There are generally two different kinds of instant noodles: (a) those that come with those square, dried out noodles wrapped in cellophane, and (b) those that come in a cup. I generally refer to the latter as “cup noodle.” I’m assuming this is the variety that you’re referring to, since you say you “pour boiling water over it.” For cup noodle, I would use silken or super soft tofu (called “soon tofu”), because it is often eaten raw or cooked a little less than extra firm or firm tofu. I would also add the tofu first, together with the spinach (i.e., at the bottom). That way, as the hot water is poured over the top, the tofu will be the beneficiary of all those flavors, as they trickle down. Otherwise, I would do everything exactly as you describe, including covering it with a plate until the noodles are cooked. Enjoy your next bowl of soon tofu ramen!

I don’t know how to be strong enough to say no when needed and it is starting to bite me in the butt. I always give in and am scared to stand up for myself and blame others for my mistakes. Have you ever struggled with any of this and if so do you have any advice. -Anonymous

Hey Anon! I love this question so much because I think so many people can relate to this–including myself! As a first year associate, I was told that it was my job to “always say yes; never say no.” I took this advice to the extreme, until one day, I was literally face down on my desk at the office, sobbing, while my phone was still ringing off the hook. On that day, I picked up the phone and I finally said “no.” And guess what? The partner on the other end–he never wanted to work with me again. I say this because I don’t want to sugarcoat this for you. There are real life consequences to your “no” and therefore, I can completely understand why you feel pressured to say “yes.” But, as you allude to, there are also real life consequences to your “yes.” It can be exhausting–physically and mentally–to constantly be ceding to the needs of those around you on the false notion that you are an endless well of resources. You are NOT.

What you give to them, you are taking from yourself.

Think of your energy as two large buckets of water. You’ve divided them in accordance with what you deem to be fair: one bucket for “them” (i.e., your family, children, friends, colleagues, employer, clients, community, etc.) and one bucket for yourself. You, and you alone, are the one who can enforce that original division of resources. And you are the one who gets to decide if, one day, there might just be enough water in the “You Bucket” to scoop some out and pour a little extra into the “Them Bucket.”

If you keep taking from the You Bucket and pouring into the Them Bucket, eventually, there won’t be enough in the You Bucket. And guess what? You’ll automatically do what you need to in order to survive. You’ll puncture a small hole in the Them Bucket, fill spoonfuls here and there, and pour them back into the You Bucket. What does this look like? You “blame others for [your] mistakes.” Your tendency to avoid taking responsibility is a defense mechanism, one that is designed to replenish what you feel has been stolen from you.

Obviously, the more effective way of dealing with this is making sure that the levels of water in the buckets remain, relatively, where you wanted them to originally. And that does mean “standing up for [your]self.” I also understand that this can be hard to do–as I mentioned, I was self-effacing to an unhealthy degree as a new lawyer. What has always helped me, though, is pretending that I’m someone else–like my little brother, my elderly mother, my best friend, my little nephew–those that I already have a very strong instinct to protect. You deserve just as much protection as those you love in your life.

But what about the partner who never wanted to work with you again? How do you deal with the unfair consequences that flow from standing up for yourself? The thing is, Anon, there’s only so much you can do to ensure that the world is moving in a direction consistent with your desires. There will be assholes in life who act nonsensically or cruelly. Disasters will befall–ones that no one could possibly be blamed for (like wildfires and traffic accidents and pandemics). Thus, it’s important that we learn to value not only those things we want in life (a stable job, a loving relationship, good food), but who we want to be in life. Because, at any given moment, those “things”? They can be taken from us–not necessarily by malice, but simply because “shit happens.” And then?

All we have left is who we are.

Wishing you all the best.

Updates/Random Things.

- EVENT POSTPONEMENT: In case you missed it, the U of I (Urbana-Champaign) event will no longer be going forward this month. However, the University is planning on rescheduling the live event for sometime in April. If you’ve already purchased your tickets, please reach out directly to the ticketing agent for further details.

- What I’m Watching: Anthony and I finally got around to watching Top Gun: Maverick. I have not watched the original Top Gun in decades, and therefore likely missed a lot of the storyline “payoffs” that occurred in the sequel. Generally speaking, the writing was average (below average in certain scenes), the acting was meh, but the action sequences had me on the edge of my seat with my mouth hanging open!! If you go in with super low expectations, I think it can be a fairly entertaining couple of hours for anyone who likes a good action flick. Also, in some lighting, Tom Cruise looks exactly the same as he did for the first movie, which I find slightly disturbing, tbh. I am also thinking of starting the new Korean drama that everyone is talking about Little Women. I’m waiting for a few more episodes to drop before I start, but if any of you have strong feelings either way on this one, let me know!

- What I’m Cooking: As some of you may know, I’ve started a “30 Day Toast Challenge,” where I make 30 different kinds of toasts for 30 days. But, not in a row! The “challenge” is coming up with and sharing 30 different ways to prepare toast. I’ve already shared three: avocado kimchi toast, avocado raspberry toast, and cheesy roasted garlic toast. You can check them all out here, if you need some inspo for your toast game. Otherwise, full recipes for all toasts featured on the challenge will be added to the TKV Meal Planner!

Parting Thoughts.

My parents stayed with me for about 10 days during the beginning of September. It was nice. They sat on my family room couch watching a Korean drama (My Mister) at my recommendation, while I sat on the floor and did Legos, an old hobby that I’ve recently resuscitated. When I was 9 or 10 years old, this exact same scene happened with regularity: my brother and I on the floor of our family room, playing, while my parents watched Korean “soap operas” (that’s what we used to call them) that they’d rented from the Korean video rental store on Dempster, a place we visited almost weekly. Only back then, I had zero interest in the dramas–could barely understand what was going on in them and was usually irritated at how well they captured my parents’ fascination when compared with my own ability to do so. Now, I not only understand everything that my parents are watching, I am the one telling them which dramas to watch!

While there was something oddly soothing about resuming our old spots in the family room, Korean spilling out of the TV while I bent over my Lego set, there was also a sharp poignancy that jabbed at me, one that could only be the consequence of knowing that I was the one who brought them to my home, I was the one who turned on the TV for them, I was the one who navigated over to Netflix, I was the one who told them to watch My Mister, and I was the one who scooped out handfuls of their favorite Korean snacks and placed them in separate small bowls for each of them so they could munch away without interrupting their drama-watching time during the mid-afternoon without dropping crumbs all over my couch.

Every time they leave my home, I am already figuring out a way to wheedle from them another visit. I love this phase of our relationship–it’s like all the fraught moments of my childhood, the fights during high school and college, and even the rollercoaster that was my young adult life–it’s as if all of it was put through a juicer and we are now all drinking from a pulpy glass of who we are, to each other, to ourselves. My mom and dad didn’t have the tools to articulate their pain when they were growing up. In fact, I’m not sure they have them today. The only reason I have been afforded the luxury of being able to step outside of myself, sometimes, to look squarely at the things that threaten to overwhelm me is because of them. It was my mother who introduced me to Dostoevsky, Steinbeck, and Anne-spelled-with-an-E, showing me that words can be powerful. It was my mother who handed me a diary when I was only 10 years old, teaching me that my words held power in them, too. It was my mother–my Korean mother–who brought me to a therapist when I was in college, when my depression had escalated beyond anything she could understand. And it was my mother, my Omma, who told me not to go to class one day during law school, who called in sick herself, so she could listen to her daughter explain to her why she sometimes wondered whether it might be better to end her life.

My parents aren’t perfect and I know that some of their trauma has impacted me in a way that makes life a little more… interesting. Challenging. Strangely, though, I don’t feel the need to “forgive them” for anything. I just want to take care of them, see them for who they are, love them for as long as I get to have them with me.

– Joanne