Shrinking Into Omma’s Skin: Overcoming A Lifetime Of Being The “Big One.”

What little girl doesn’t grow up wanting to be exactly like her mother? I was certainly no exception to that rule. I wanted to talk like my mom, I wanted to dress like my mom, I wanted to cook like my mom, I even wanted to chew gum like my mom.

Unfortunately, though my mother gave me so much, she couldn’t give to me the one thing I wanted most of all. More than anything in all the world —I wanted to look like my mom.

My mother is a sparrow.

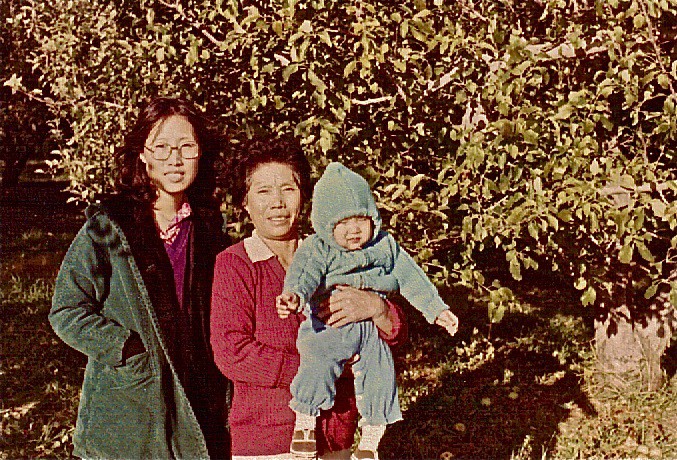

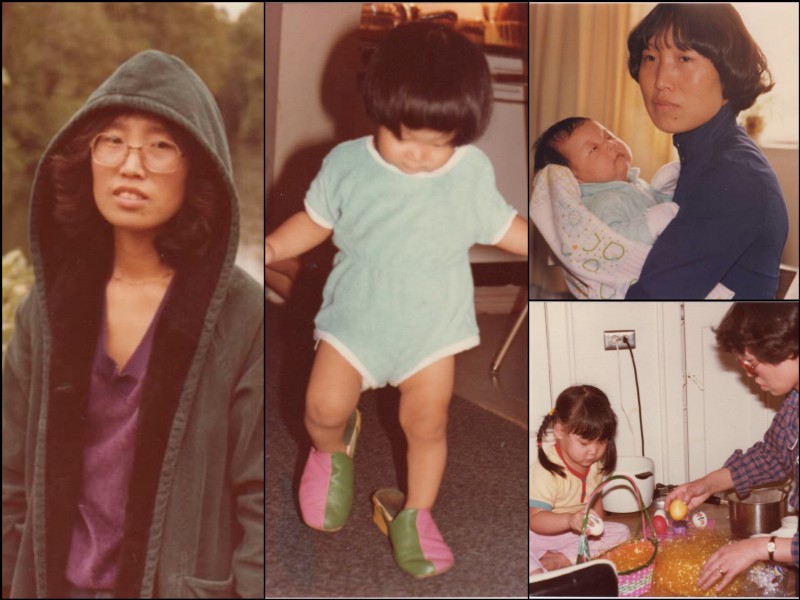

She was 87 lbs—when she was nine months pregnant with me. All her life, she has struggled with low cholesterol, low blood pressure, and being underweight—which, in my mind, is what always allowed her to fly around from PTA meetings, to the hospital (where she was a nurse for over three decades), church meetings, recitals, birthday parties, and field trips with impossible grace. When I try and describe my mother, I often think of this old photo of us—she is sitting on the bed with me (I must have been maybe 2 years old) in a cloud of yellow silk. Sunlight is pouring in from somewhere, so that you can just see the silhouette of her shallow breasts, the dime-sized scar on her shoulder from the smallpox vaccine she got when she was little. Her pale face is tilted towards me, while I am doing my best imitation of a beach-ball squatting on her bed.

I grew up taking after a dumpling much more than a bird. I have broad shoulders, a heavy jaw, thighs that look a great deal more like tree trunks than branches, and an atypically large ass (as my grandmother enjoyed reminding me at every opportunity). I was 12 years old the day I outgrew my mother’s hand-me-down bras, and it was then that I knew I’d passed the point of no return: I would never, ever look like my mother.

Instead, I would always be the Big One.

Whether or not it is a stereotype, the vast majority of Korean women I know are quite a bit smaller than I am. This, of course, started with my mother–the tiniest of all of them–but extended to my aunts, my cousins, my girlfriends, even the women I’d see at the Korean grocery store. All of these women would hit the panic button and crash diet the minute the scale tipped over 105 lbs, while for me, the notion of weighing 105 lbs was unfathomable–even at 5’1″. For as long as I can remember, I have been weighed in the eyes of all these small Asian women who have actually earned the right to be called “petite.” And, I have been ashamed of my failure to be one of them my entire fucking life.

Throughout junior high and high school, I “got by” on brains and talent and I was “skinny enough” to occasionally earn the “pretty” tag when introduced to my parents’ friends or colleagues, but was much more often introduced as the “smart one” (i.e., 우리 똑똑한 딸). For as long as I could remember, my mother was always getting after me about shedding “just 10 pounds” so that I could be “perfect.” I don’t think she knew that those “just 10 pounds” forced a wedge between us. I buried the distance that sprang up between me and my mother deep into a crack that closed up like a tender wound in my chest.

It never healed.

Against my mother’s advice, I married the first man I ever loved. Though my mother’s voice was fierce, her bones were hollow and even she lacked the strength to extract my heart from the trouble that was my marriage. She watched, year after year, as I stifled the voice that had been my birthright in favor of eating my pain. Literally. I was a not-overweight college freshman (5’1″ and around 125 lbs) when I met my ex-husband in 1997. Fast forward 12 years to 2009—by which time I had swaddled both my mind and body in the tantalizing perfume of inertia—and weighed an astonishing 187 lbs. By this time, the “advice” from my parents was not limited to “just the last 10 pounds.” They counseled against visiting my relatives in Korea, for fear I would be too embarassed by my size. They suggested I decline a slice of my own birthday cake because I was “getting too fat.” And my grandmother, God love her, would mutter, “ayooo, somehow your ass has grown even bigger…,” every Christmas.

[Don’t get me wrong. I do not say these things to criticize my family. As most of us Korean girls know, this is, to the “First Generation,” a perverse mechanism for showing “love.” An effort to protect us from the far less forgiving scrutiny of society at large. As is often the case when our parents or loved ones fuck up, “they meant well.”]

My mother is a very proud woman — particularly when it comes to men. She thus found it hard to watch her only daughter staying with a man who didn’t treat her well. After each explosive fight with my ex-husband, I would show up at my mother’s doorstep (for the 100th time), my face red with tears. I didn’t have to say anything—I never did. She merely opened the door and would say,

“또? Again?”

She would sit me down on her peach leather couch with a warm cup of coffee between her small hands and we would have the same conversation we’d had a dozen times already.

“Why do you keep going back?”

At first, I think it was a genuine question. But after years of the same question, it was hard for my mother to hide the contempt in her words. One evening in 2010, I showed up at her doorstep at 2 in the morning in my pajamas, barefoot, and with my dog panting in my arms. I told her, “This time, I don’t think I can go back. I’m getting a divorce.” I will never forget the response of my 87 lb. mother (loosely translated into English):

“If he shows his face here, I am going to beat the shit out of him.”

I did go back. Physically, my body returned to our house, but something turned in me that night. I gave up on my marriage that night. And somewhere, buried deep inside of me, I hoped I could one day [soon] make my mother proud by actually leaving and not going back.

Eventually, in March 2013, 16 years after falling in love, I left my husband and our 2400 square foot townhouse in a sleepy suburb for a tiny apartment in the city. By that time, I had convinced myself that my skin had grown thick enough to deal with the humiliation of the dreaded “when are you due?” comment by strangers in the elevator or watching my mother laugh behind her slim hands when someone gasped, “Well, how did someone your size give birth to her?” I had grown quite adept at avoiding the camera lens (including my own) and using my ever-expanding girth as a built-in forcefield against social interaction of any kind (despite my sister-in-law’s relentless matchmaking prowess). Truth is, I had a lot on my plate—unpacking 16 years of my life into a much smaller space, a stack of divorce papers, a job that demanded as much from me as ever, and, of course, french fries.

In January 2014, I decided it was finally time to do something about my weight. It was definitely not the first time I’d resolved to lose weight (I had tried just about every “diet” known to man, including low fat, low carb, Paleo, Zone, Weight Watchers, and liposuction), but it would be the first time I’d attempt to do so the “healthy way,” as my shrink suggested. I picked up a copy of James Duigan’s Clean & Lean Diet—which was way more accessible than “lo-carb” or “lo-fat” or “lo-cal” and ordered Tony Horton’s Power90 (the P90x for geriatrics) DVDs. The official kick-off date for Project “The New Me” was on Monday, January 13, 2014.

I’d like to tell you that the fat just melted right off. But, the truth is the truth is the truth: there is no trick to losing fat. Eat right and exercise. As with virtually everything else in my life, I’d grown quite chummy with the extra padding, and contrary to what one might believe, there was a fair bit of bitter mixed in with the sweet every time another inch disappeared. A wise Unni of mine once posted on her Facebook, “Confidence is a hard earned thing.” I felt wholly unprepared for the Confidence my new body would bring; but, I had learned a thing or two from digging through the debris from my marriage—it’s better to move forward into a dark future than stay put in the bright and washed out background of the past.

Day 90 came and went. I took my obligatory 90-day side-by-side and got a bunch of notes on my Instagram account. I got bored with Tony Horton’s Power90 and started running along the lakeshore (my second apartment building was right on Lake Michigan). My face shrank. My body started to “ripple” instead of “jiggle.” My girlfriend told me “This is different from the last time you lost weight. You look strong.” My mother told me, often, “You look great!! Keep up the good work!” Every morning, I would run my hand along my obliques and marvel at meeting muscles with whom I’d never been acquainted. For the first time in my life, I decided that I would risk skin cancer by “laying out” at the pool and, for the first time in my life, a man I didn’t know asked me how often I went to the gym, since “it’s obvious you work out a lot.”

These are the “highs” and wouldn’t it be great if I could tell you that there were/are no “lows.” After losing more than 60 lbs, I was addicted to the “highs,” to seeing another pound melt away, feeling another pair of “goal jeans” slide over my hips. And with all of the joy that came with running past another milestone, it became all too easy for me to equate my weight with my worth.

As with any high… ultimately, I came crashing down. And it was anything but pretty.

The weight loss slowed to a snail’s pace. Despite being told by my friends, my cousins, and my mom that I really needed to “quit dieting,” I was constantly chasing after just “those last 10 lbs.” But, inevitably, those last 10 lbs grew ever more elusive as I got smaller. After over a year of restrictive eating and more and more cardio, my metabolism had cratered.

Of course, the only rational solution (to me) was to eat less and run more. By August 2015, I was eating between 300-800 calories a day and running 30+ miles per week. On Sundays, after starving all week, I would binge on donuts, fried foods, and greasy sandwiches — often in the dark, close to midnight, when no one was around and I could hide my shame. On Mondays, I would “fast” as a penalty for my Sunday indulgences.

I was terrified that my new boyfriend would dump me for being too fat. As the number on the scale refused to budge, even though I was the lightest I had ever been as an adult, I was convinced that it was only a matter of time before I grew prohibitively unattractive. Out of desperation, I would go on sprees of eating nothing but 3 truffles or 3 biscotti a day, while downing laxatives for breakfast and dinner. My hair started to fall out; I broke out into a rash that became difficult to hide; and I was freezing all the time, from the inside out. I started carrying a little cash with me on my runs, because I was worried I might pass out.

One sunny afternoon, after weighing myself for the 17th time that day and seeing the same damn number I did the day before, I started to cry. A lot.

Not the pretty crying, the kind my mother was so good at, with one hand over her mouth and tears rolling down her frail face, but gross hiccuping sobs, my body squatting over the scale until I started seeing stars from the lack of oxygen. And food. I called my therapist — the one who had helped me through my divorce — and wailed into the phone,

“You don’t understand, Colette. I’m too fat.

I’ll never be skinny enough. I’ll never be good enough. I’ll never be good enough for him!”

I think there — right there — was my rock bottom. I equated being “fat” with being “unworthy.” And not just unworthy in general, but “unworthy” to be loved — by my parents, by my boyfriend, by anyone.

It’s been 20 months since that panicked call to Colette. I wish I could tell you that over the past 20 months, I stopped caring about my weight. The God’s honest truth is, I am still obsessed with my body. Not a day goes by where I haven’t thought about whether I’m skinny enough, slid my hands over my hips wishing I could dissolve them with my touch, compared my body to the women I see on the street, calculated the number of calories in my breakfast. Just the other night, I dreamt that while changing in front of my mother, she sighed and shook her head in unsurprised disappointment and commented, “You’ve gained weight again.” It took me several hours into my day to realize that it had been just a dream.

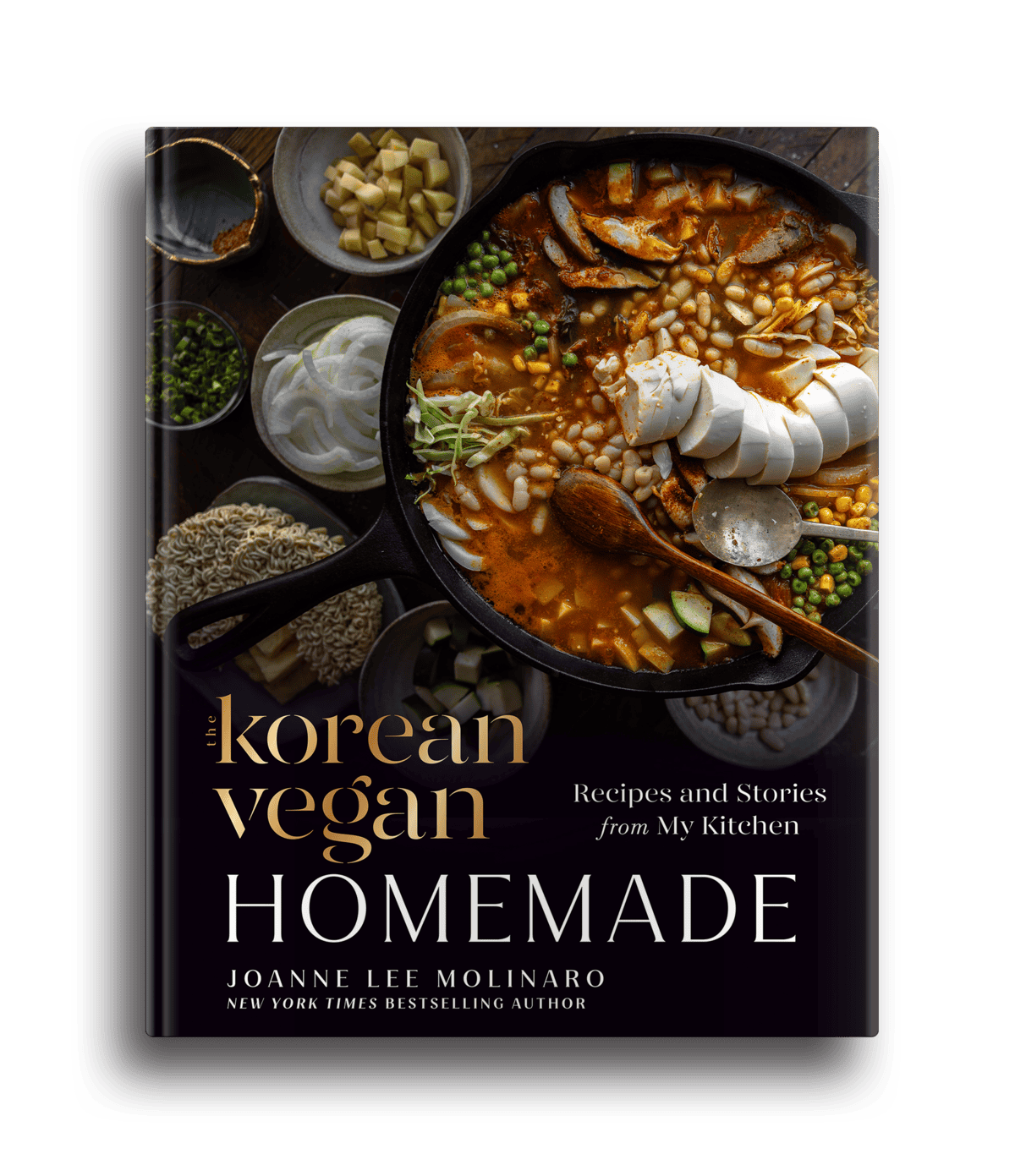

However, over the past 20 months, I’ve been seeing a therapist who specializes in “disordered eating.” I’ve thrown away my scale; I trained for and completed my first half marathon; I started a food blog, of all things; I traded in all my designer handbags for race bibs and my fancy shoes for running shoes. Although I still count calories, I now try to make sure I’m eating enough, and once I did that, well whaddya know — the urge to binge on donuts and french fries suddenly disappeared by itself.

But, of all the changes in my life in the past 20 months,

the most disruptive has been my choice to go vegan.

Every vegan I’ve ever spoken to has gone out of their ways to extol the many virtues of adopting a plant based diet.

I’m not “every vegan.”

Don’t get me wrong. There are some very important “benefits” to going vegan for someone who has a fairly dysfunctional relationship with food. For me, going vegan has served as an excellent “crutch” as I hobble around a gastronomic landscape without the “low calorie” or “low carb” guard rails. Put simply, it’s easier for me to justify eating more because I know, in the back of my mind, that I’m actually still eating a lot less than the “average Jo.” Do the math — I would have to eat half a dozen servings of chickpeas to equal 2 small pieces of fried chicken or 3 blocks of tofu for one steak. Not only that, I can readily satisfy my pernicious appetite for alpha bitch control with every single vegan bite, since I am now restricting far more foods than I ever have.

But, however many articles you read about people who have successfully used veganism to “recover” from an eating disorder, in my mind, it’s still a crutch, and a crutch, by its very definition, should be “transitory,” as in — not permanent. Does that mean I’m going to stop being vegan now? No. But it does mean that I can’t keep using veganism as a way to avoid walking around on my own two legs. Put another way, it means that I can’t hide behind a diet consisting of fruits, nuts, vegetables, and moral platitudes from facing the hardest thing I will ever do.

“Loving yourself will be the hardest thing you will ever do,” my food therapist, Rachel, warned me on my first visit. I almost walked out. I did not sign up for therapy so that I could learn how to “love myself.” Although I would not have admitted it at the time, I signed up for therapy in order to strategize a more sustainable method for losing fat. If these sessions were going to be devoted to hippie-dippy-love-yourself-bullshit, they would be short-lived.

Which is what I said to her, in the most diplomatic way possible.

She smiled patiently. And repeated,

“Loving yourself will be the hardest thing you will ever do.”

And, just in case I missed it, she said once more,

“Loving yourself will be the hardest thing you will ever do.”

Maybe repeating the phrase three times somehow guaranteed that it would come true. Because however hard I try, whatever maneuverings I employ, I always manage to come back to ground zero, where I must continue to tell myself,

You are more than the number on your scale,

the number on the back of your jeans,

the number on the top right corner of the treadmill, or

the number at the bottom of your food diary.

Sometimes, it’s hard to describe what love looks like — I recall sitting in the bathtub with my mother when I was nine years old. She had spent the past hour scrubbing me down within an inch of my life. Even then at just nine years old, I knew that I was rounder and more padded than I should be. Looking down at my belly, I asked myself, again, how it was possible that a bird like her could give birth to something like me. We watched as the bathwater circled our bodies and all the dark flecks of 때 (exfoliated skin) drained, and while toweling me off, Omma jokes,

“I’ll bet you lost 10 lbs from that bath!”

At first, I laugh at my mother’s joke. But then, my nine-year old self looks up through baby eyelashes, still trembling with bathwater, and wonders wistfully,

“Really? Do you really think I lost weight from the bath?”

My heart breaks a little when I think of this.

I tell myself that this fleeting heartbreak is what love looks like.

Rachel reassures me over and over again, “Anthony loves you for more than your body. He loves your brain.”

For a long time, this only meant that I would continue to be introduced as the “smart one,” as some sort of implicit consolation for the fact that I was fat and ugly. Over the past 6 months, though, since going vegan, my attitude about food — and by extrapolation, my body — has shifted.

I think most people — me included — eat because we like the taste of certain foods. My mouth waters at the sight of kimchi and chocolate cake. And for a long time, the smell of bacon affected me the same way it affects the majority of red-blooded Americans. I used to tell people, my last meal on earth would consist of Korean style pork belly, rice, and miso soup.

But, like many of you, I have a difficult time coping with overt and senseless cruelty to anyone — friends, family, even strangers on the street. I get particularly upset when people are mean to the elderly, children, and, of course, animals. The notion that such meanness exists against the defenseless is profoundly frightening to me.

Now, with every bite of food I take, it’s no longer just a calculation of calories, carbs, and fat v. its utility at satisfying hunger and taste. While that calculation occurs, I am also reminded — with every bite — that I’m actually doing something good, something really and unquestionably good. Good for my body, good for the earth, good for the animals I’ve always adored.

This choice for compassion, together with all the choices I’ve ever made and will continue to make — these are the things that determine my worth. Not my bikini-unready bod.

When my mother was just a toddler, my grandparents whisked her out of their home in North Korea and literally carried her to what is now South Korea. She spent most of her childhood living off the charity of the village they settled in, digging through the dirt on her hands and knees for left over crops and sweet potatoes. She excelled at school even when her parents never had enough money for books, uniforms, or shoes. After my grandmother buried three little babies in an attempt to have a son, my mother assumed that role for herself, learning how to take care of the family farm under my grandfather’s careful instruction. She immigrated to the United States with no job, barely any money, and unable to speak English with the hope of improving not just her own fortune, but that of all those back home in Korea. She worked her ass off as a nurse and climbed the ranks to ultimately become the Director of the Emergency Department at a hospital in Chicago. She raised two kids who’ve never smoked or done any drugs, ever, and who both spoke perfect American English. And, even with all this, she finds time to write and publish her poetry, practice her calligraphy, and sing in the church choir.

I catalogue the choices I’ve made over the past decade to bring me where I am.

The time I slept on my office floor in my suit because I knew I would have to get back to work in just a few hours.

The time I ran .75 miles along the lakeshore path after not working out for over 3 years.

The time I picked up a camera and snapped a photo of my mother’s hands hugging a cup of tea.

The time I wrote a poem about my mother, about her hands, a cup of tea, Lake Michigan, and the quiet sorrow I inherited from her.

The time I wrote a blog about why I love Korean food and why I won’t let going vegan stop me from eating kimchi.

The time I kissed my dog, Daisy, on her back, after leaving her at my mother’s, where she is happier and healthier.

The time I scratched a man’s back, because my nails were long and his skin was soft, and we were both desperate for any semblance of joy to combat our despair.

The time I drove a car packed with 16 years of my life in the trunk towards the city;

telling my mother for the very last time,

“this time, I’m not going back.”

I realize, now, that I’ve been thinking of it all wrong. it’s not about shrinking into my mother’s skin. No.

All this time, I’ve been trying to grow into it.

I needed to read your fight story/love story and it made me cry, laugh, and relate. Thank you for sharing this. I am metis and born from love, immigration, pride, fight. Expectations for survival run so deep and so does the need to just be okay amidst chaos. Do we thrive on control? Do we have to be the best? Our parents/aunties and uncles, and g parents will always be tougher and more deserving although they fought so strongly to gift us a more peaceful life then they knew, so we could enjoy being. Food was scarce and yet love, was always the power behind everything. I’m grateful to have found you on fb, but I’m even more grateful that you have fought for your peace, because the younger generations need come back stories. You have blessed my morning 💛🤲 Blessings to you and your family

Cher

Your voice is so strong, beautiful, and powerful in this story. I loved reading it, I loved the way you wrote it, and told it, and I love your spirit, too.

Thank you for writing such a beautiful piece. I just stumbled on your blog looking for Korean vegan food, so it was a surprise to discover this gem along the way. I’m a Korean-American college student (I’m in Chicago too!) and I’m always really overjoyed to know that I’m not alone. So happy for you, with all the progress you’ve made!! Self-love is a journey isn’t it. Sending you love!!!

Yay! Another Chicago Korean American! And yes! I wrote this post to let women know that they do not struggle alone with these issues. Body image is such a tangle and I’m glad this resonated with you. Best of luck in school!

Your story almost brought me to tears as it is very much my own with a Haitian dynamic. Thank you so much for sharing this I have been on the fence on sharing the more intimate parts of my story because it felt to raw. It was so great meeting you this week for the influencer summit. I am so in love with your writing style its beautiful. I look forward to connecting with you again.

Love and Light,

Nzingah

Nzingah! It was such a pleasure meeting with you earlier this month! Thank you so much for reading my story and for reaching out. I think there are so many women out there who feel insecure about their size, in relation to what they perceive to the “cultural norm”–whether it’s an American ideal or something endemic to other cultures. The reason I share these things (which, even I sometimes think “TMI….?”) is because I want women who don’t feel comfortable about sharing to know: “You are NOT alone.” Conversely, I have joyously found that I AM NOT ALONE!! Loved meeting you and hope to see you again very soon! Joanne.

I absolutely love your story. I often think how everyone has a story, there are many stories unheard. Some people see the outer appearance, yet never seen the hardship others face. It seems like your walking through fire to get where you are today. In my journey, one thing I’ve learned is to love everyone for who they are. We don’t know why they are the way they are but still love overcomes all. I follow you on IG. I’m a huge Korean food lover, I actually have learned Korean words and phrases from the Koreandramas haha! I love other cultures. I’m Happy for you! I will pray your strength in God. I became vegan cause I wanted to treat my body well plus I lost my mother 4 years ago due to health reasons.

Teresa, so sorry to hear about your mother. I think many of us try to make something positive out of grief and what could be more positive than embracing a more healthful AND compassionate you? Good luck to you in your quest to do your mother proud. I’m so glad I can be part of that journey. <3

Ashley, I loved this beautiful ramble-y comment. I’m so glad that something I shared inspired it. You are so right about needing to love oneself as God intended. I’m so happy that you have both God and a husband in your life who helps you day-to-day. <3<3<3

Anani, thank you so much for this comment. I’m so glad that folks have been able to relate to this.

Thank you for this brave, honest, and inspirational post. I shared some of your experiences, feeling I was not Korean enough because of my weight. It’s a little bittersweet to realize that there are likely so many Korean Americans who have felt this way. Last month, I became a vegan for both ethical and health reasons, equally, and for me, it has become a surprising source of happiness and fulfillment because I feel good just knowing I have chosen the compassionate option. I searched vegan Korean, looking for Korean vegan bloggers, and I’m happy to have found yours. Thank you.

Jenny, thank you so much for this heartfelt comment. I totally get what you mean about not feeling “Korean enough” and still struggle with this today. Here’s to a different kind of “Korean”–or, a “korean vegan.” 🙂

I stumbled on this looking for vegan Korean recipes and I just couldn’t stop reading. I am so proud of you for all the progress you made physically, mentally and emotionally. I know I’m just a stranger but your words really moved me xo

Tanya, hearing that another woman is “proud of me” is incredible. Thank you so much for this unbelievable moving comment.

What a beautifully-written piece. Thank you for sharing this! I am old enough to be your mom but I used vegetarianism in much the same way in the 80s…to escape a young adulthood of disordered eating…I am still on the compassionate path–now veganism–but am always careful to watch for signs of eating disorders in myself and my clients…it’s a lifelong path. (I also chuckled at your descriptions of the impossibility of learning to love yourself–hard isn’t it?) I am very excited to learn more about veganizing Korean food from you…and maybe some great places to eat in Chicago (outside our regular faves) as we are right next door in Michigan. Plus those cookies look amazing…I love to veganize kenji s food. If I were your fairy godmother I would give you a dream in which a Korean version of Glinda the good witch in the Wizard of Oz shows you a montage of all those photos of yourself inside a big gauzy soap bubble and just before she pops it, she whispers: so you see my dear, you really were beautiful all along…you just didn’t know it.

Sue, I literally got shivers from reading this comment. Thank you so much, and whether or not it was your intent, I started to believe in fairy godmothers again. <3 I will be posting more recipes as soon as my blogs new theme gets set, but in the meantime, I hope you continue to enjoy my journey as a woman and a vegan.

Wow, this was such a beautiful and inspirational read. I recently stumbled upon your account on IG and am loving your writing style. I am not vegan nor can ever be ( like, I love samgyupsal and stuff too much), but reading about and following your transformation into veganism is inspirational.

Miss Kim, thank you so much for this comment! But you give yourself too little credit: I used to love samgyupsal too, and I changed! So can you (if you want to). I do miss samgyupsal, though, and basically avoid all Korean BBQ restaurants as a result!

Oh my word, that was such a powerful and inspiring read. Much respect for you, Joanne! 🙂

Thanks so much Eunice. It was one of those “I need to get this out of me!” posts. <3

This is so beautiful. I’m so sorry for all the hardships that you had to experience–truly, it must’ve been really hard. As someone who also put her worth in numbers and looks and fell into a near-death state, I can relate to nearly every word. I’m glad you were able to find your path to recovery and have found a balance. I know it’s a constant struggle, but I’m so happy that you have a mother who you can rely upon and seek for help. I know my mom would’ve done the same, and it’s so hard without her, but people like you inspire and encourage me to continue this journey and attempt to find my happy and HEALTHY place.

I wish I could meet you some time! You and your journey mean so much to me.

Michelle, it truly warms my heart to know that this post resonated with you. We women really need to support each other! And who knows, our paths may cross!

Thank you for sharing your journey. I found your blog while searching for vegan Korean recipes. Reading about learning to love yourself and accepting that you (just as you are) are worthy of love struck a chord with me. I’ve been through years of therapy trying to reconcile being a first generation Asian American with immigrant parents who find endearment in names like “big one” or who try to be helpful by telling to not to eat too much. Your story resonates with my personal struggle and I’m looking forward to reading more!

Darlene, our parents (and grandparents) grew up in a different time, when food was scarce and ribcages poked out of their skin. This led to two things: (a) them feeding us too much food, and (b) us not having our ribs sticking out of our skin! The struggle is constant, but I hope that we can learn from one another as we continue climbing our alpine path.

Thank you for sharing your story. Thanj you a million times! I am writing this comment while my daughter is napping on my arm. I have tears rolling down my face because everything you wrote touched my heart. I’m new to eating plantbased, since October 2016. I’m not perfect. I need to lose weight, being 5’1″ and at a high 150’s lbs… also being half korean, I grew up being the big girl, called out made fun of for my big butt and just overall looking different… I lost mother to bile duct cancer in 2012, and miss her calling me and asking me have I been walking outside for weight loss? Or saying I should go out with her to walk while she plays golf… I never got around to do tgat and wish everyday that I did… Anyway let me quit my ramblings here… i want to say that I think reading this has opened up something in me. You see, I’ve been on thus journey of trying to love myself, because for the majority of my life I’ve literally hated who i was because I was so different. Being half korean, and not accepting my other side ( i am half puerto rican ) made me feel unworthy, not lovable, an outcast… or maybe it was just me who put myself in those labels. .. my point is that your post has helped me open my eyes and want to be open and accept myself. So thank you! ! ♡♡♡

You are one BEAUTIFUL woman. Not just on the outside but on the inside too.

I love reading your posts and this one has touched me and I can relate to so much of it, it’s crazy.

Thanks for posting such a personal story.

This was so sad and beautiful at the same time. Body dysmorphia is so present in every female and especially harsh on some people. I feel like we went through the same thing, and I’m so glad I read your story. My mum was also a twig growing up and I have a twin sister who’s bird-boned too. So, I’ve always been labeled as the “fat” sister. I think it’s stories like yours and forums that had helped me go through my eating disorder.

You’re an amazing human being and I love your food and stories xxx i use food as reward or punishment and still haven’t managed to turn the switch in a positive way in order to lose and keep weight off. Thanks for sharing this (: xx

Hi Amy!! Thank you so much for dropping by and leaving this lovely heart-studded comment. 🙂 I am so glad that reading this shed a little light onto your own journey. Each of our paths are unique, but it’s important to stop and say “hi!” when we cross a kindred spirit! <3

Yes! Shout to the Big One!! Ha! And I figured that there would be a lot of cross-cultural intersections on this issue. Beauty is definitely seen through the eyes of heritage. And thank you so much for your kind comments and observations. Sometimes, you have to fake it till you make it, ya know? I try to act confident even when I don’t feel it, and it sometimes actually helps! Cheering you right back on IG!!!

Thank you for being brave enough to share your story! My mother is Korean (father is caucasian) and I also know all to well of the constant comments about my weight growing up. I did not inherit the typical Korean body type but have my father’s European genes and body shape (hour glass and hearty). Growing up I always heard it from my mother and brother.

I will never forget the time my mother told me “You’ll never find a good husband if you don’t lose weight.” I was at my heaviest (175lbs. on a 5’5 frame) in college, drinking 6 nights out of the week and eating pizza or Chik-Fil-A before at 2am before going to bed. After college, I lost most of the weight and then got into CrossFit. I got down to 135lbs. but was strong and healthy. Then it turned into “You’re too skinny. Don’t do too much.” I’ve always been too fat or too skinny for my mother. I think I then realized that I’ll never be perfect in her eyes and I quit caring about what she thought about my weight and figure.

I love my mother dearly and I know it was meant well but I have moved past caring what she thinks. Every time I talk to her, she asks if I’m still going to the gym regularly (I still haven’t been able to get back to my pre-pregnancy weight or shape after my second child) and I know exactly what she is saying. But I just brush it off and I’ve learned to accept my body and know that I will “get back to that place” again one day. It’ll just take some more time. Plus, I’m vegetarian which made my mother’s head spin back in 2007. I’ve played around with veganism on and off and hope to be fully vegan in the future! Again, thank you so much for sharing your story!

This comment straight up made me cry. It’s perfect on all fours. I am so happy for you!!! You’re going to be a mama!!!!!

Thank you for opening your heart to us. You are an inspiration to me. I definitely can relate to this. I’ve been trying to loose weight for a couple years now and even with a vegan lifestyle I always find a lot of junky food. My dad and my sister called me one day and told me “you’re so fat and your ass is so big” while they were laughing. My mom came last summer and when she met a friend, she introduced me as the daughter who was a little bit fat. I don’t even want to visit my family anymore because I know what is the first thing they’re going to say about me. I chose a vegan lifestyle because of the animals but now I’m focusing on more healthy food and an active living. I started blogging because it helps me to stay motivated and also to inspire people. You are beautiful inside and outside. Thank you so much for inspiring me everyday. A lot of us are struggling with situations like this but we forget that we’re not alone and there’s always an answer. Much love to you ?

OMG MARIELA I LOVE YOUR IG!!! Hi Hi!!! I totally hear ya on your situation with your family. And I also congratulate you on your choice to go vegan and embracing a more active life!! All of those things will increase your confidence and help you to get in touch with the REAL you–the person who makes you beautiful no matter your size or your parents’ opinions. Your IG feed is beautiful and inspiring and that, in and of itself, should show you how much beauty there is in you to see and give! <3

Your story serves to remind me as a mother to always be mindful of my attitude with my weight and body image. I have to girls… Big job ahead in raising confident young women.

My hangups/skeletons cannot spill over their lives.

I’ve always been the big one and not as pretty as my sisters or my mom according to standards of outsiders.

Such things can really mess with your head.

You’ve conquered so much challenges and have inspired me to really get serious in being healthier.

Much gratitude for your transparency and fighting for you!

Windie, I absolutely love love this comment. I often think about this myself–even though I am not a mother (yet). How much of what we do instinctively do we pass onto others? Whether our children, friends, or colleagues? I applaud your mindfulness as a woman and a mother and am so grateful for your willingness to share this with me. <3

You’ve probably seen these, but just in case

http://www.thefullhelping.com/green-recovery/

Thank you for taking the time to Share this. It has inspired me so much with my own journey of eating health and taking care of my self mentally and physically.

Hi Haleemah! So glad my story has encouraged you. That’s definitely a large reason for writing it! Much love to you and strength to your journey. <3

Thank you for sharing such a personal story. My Chinese grandmother and mother, to this day, would make indirect comments about my weight. I’ve had 2 kids but that’s no excuse. I’m at 128 and 5’3″ and still hear the ‘fat’ comments. It’s and emotional struggle for sure, and not always a physical one.

WOW!! I think most women would KILL to weigh 128 after two kids!!! Sigh. I swear, our parents and grandparents had a fundamentally different metabolism in order to help them survive war time, right? That is the only explanation! My mom eats like a horse and LOSES weight! WTF?? Regardless, being a mother is the hardest job in all the world and your kids adore you at whatever size you are! That’s what COUNTS!

This is so incredibly heartfelt and beautifully honest post. Thank you so much for sharing, it means so much I can’t even put into words. Sending so much love to you.

Hi hi Kelly!!! Thank you for dropping into my blog!! Your kind words and friendliness on IG are so encouraging. 🙂 So happy we met through there and sending many many hearts right back to you!!! <3 <3 <3

Super thoughtful, raw , honest, beautiful and moving. It must have been emotional for you to write and share this, Joanne.

Yes, loving yourself is the hardest thing you will ever do…I still struggle with it from time to time (so much that those words “love yourself” make me cry a little). And I did cry a little while reading this, lol.

Anyway, I’m almost at a loss for words here…I loved this post!

Xx

Hi Heidi!!! Isn’t it amazing how we run into commonalities on the interwebs? I wrote this partly because I knew that lots of other women probably felt a lot of the same things even though they don’t ever talk about it. So glad it resonated with you and to have met you through IG!! <333

Thank you for sharing your story! It’s a deeply personal account of how far you’ve come. You are a courageous, beautiful woman! It’s truly inspiring. I could relate to some of what you wrote due to having a Korean mother who always tried to “help” me by telling me to lose weight. This same mother rarely cooked meals at home so I’m learning how to make Korean food from you here. Thank you.

Thanks Esther!! Eating and culture are almost impossible to separate. So glad to hear the you are embracing a positive way to embrace your heritage and your food!!

Thank you so much for posting this. I am a little shocked that I haven’t come across your blog yet, because this story…sounds just like mine. Like, word for word. It feels as if I could have written this exact story about me. Reading your essay made me cry tears of both sympathy and empathy and I am so glad to know that I am not alone. And for anyone who is struggling with weight issues, cross-cultural issues, relationship issues, and self-image issues, it is so important to have someone like you share her own experience. I’m so glad you’re doing better these days. It’ll always be an uphill battles, but it gets easier. And I’m so glad you have stayed strong for so long 🙂

Mari,

Thank you so much for reading my story and for reaching out. Amazingly, many many women (and even men) have reached out to me here or on my Instagram saying so much of the same thing: that the words I wrote were words they often repeated to themselves, that my story is very similar to their own. You are NOT ALONE!! That is why I wrote this! To prove to you and to so many others that we struggle with the same things and that we can learn from each other! That we can empower one another! Thank you so much for reaching out and for proving that we are in it together. <3<3<3

Joanne.

Wow! This is beautiful. Thank you. I didn’t expect to be so moved when I came to your site looking for vegan Korean recipes!

Powerful.

Thank you so much Diane! I hope you find some good recipes too!