One Afternoon at the Peninsula.

After finishing up my very first year as an associate at my law firm, I invited my entire family—my mom, dad, brother, aunts, uncle, cousin, and even my 80+ year old grandmother—to the Peninsula Hotel for afternoon tea. We arrived at the iconic hotel on Superior and all 13 of us filed past the pair of gargoyled lions and into the revolving door, as a slight man uniformed in all white pressed his gloved hands against the glass so that we wouldn’t have to. Our reservation was at The Lobby, the hotel’s premier restaurant, renown for its Sunday brunch and afternoon tea service. As we waited for the brass doors of the elevator shaft to admit us, I touched my hair. I had taken pains with my appearance that day—I wore a pale yellow frock with delicate flowers darting across the skirt and a wide sash around my waist. I ironed my hair and pressed the curls so they looked more happenstance than artifice. I even had makeup on.

The elevator finally arrived and three guests ahead of us went in. My family followed. My cousins tittered nervously, my brother looked uncomfortable but stared straight ahead. My parents were silent. My grandmother wedged herself into a corner. It was a tight squeeze, and perhaps it would have made more sense for us to take two cars up to the restaurant, but I could sense that no one wanted to be separated. As the doors slid closed, I heard one of the women who had gotten in before us—a petite young woman with glossy brown hair, sparkling diamond studs hanging from her lobes, and a pristine white Mon Cler jacket—sniff rather loudly as my grandmother leaned back into her space. She then burst into a fit of not kind giggles as she whispered something to her companion, also bedecked in casual couture.

Standing at the back of the elevator, I could feel a bead of sweat trickling down between my shoulder blades, as I attempted to put a few more inches between myself and the woman standing next to me—a young black woman with her hair pulled back in a tight pony tail sporting a form-fitting black hoodie and running tights—as if I could—should—compensate for my grandmother’s faux pas. Perhaps taking a cue from me, the young black woman also adjusted her position and sidled away from the two aforementioned women to her right. As she did, the diamond studded one murmured, “Oh, you’re ok. It’s not YOU.”

In such a small space, it was impossible for all of us who understood English not to grasp the real meaning of her words. “It’s not YOU.” It’s THEM. More beads of sweat between my shoulder blades. My face flushed as a big ball of fury, shame, confusion, and anxiety threatened to crush all the intentions that drove me to bring my family—none of whom had ever dreamed of visiting a five star hotel—and my grandmother—who still had nightmares about the war and stood with her walnut hands clasped behind her curved back—to The Peninsula. I stared straight ahead, past the wispy black curls (dyed) of my Hahlmuhnee, wondering how long before we’d be freed from our vintage brass prison.

“Mmm-kay.”

That wasn’t me. And it definitely wasn’t anyone in my family. None of us could inject that level of contempt into two syllables. I cocked my head and stole a glance at the sporty black woman next to me. She looked both irritated and resolute. Tired. And the Mon Cler ladies next to her were not having it.

“Hey, what’s your problem? I told you, it’s not YOU.”

“I don’t have a problem,” she answered without missing a beat, without raising her voice above a mutter, without shifting her gaze an inch from the double doors, which finally began to open. My grandmother ambled out, followed by two huffy and puffy white jackets and a cloud of Chanel No. 5. As we walked down the wide corridor lined with glass cases shimmering with the largest diamonds I had ever seen, I turned to the woman who’d managed to say so much in so few words.

“Those girls are crazy,” I said with a shy smile.

“Yeah, they are. Don’t pay them no mind,” she advised before heading towards another bank of elevators past the restaurant. I looked past her at my Hahlmuhnee, who remained oblivious to the jewels that glowed all around her, the chandeliers that hung like upside down tiaras from the ceiling, the soft tete-a-tete of champaign glasses that threatened to unfurl the bullishness that led me to believe I could be good enough for admission to a club that seemed reserved for those who looked nothing like me, something Sporty Girl had understood implicitly in a way I was too spineless to absorb.

Later, over a cup of green tea and a plate of stiff British scones, my aunt looked over at me and said, “Joanne, you are so pretty.” I smiled back at her. But inside, I kept thinking of Sporty Girl, her quiet defiance on our behalf, and my instinct to internalize the gaze that rendered my family gratuitous. I thought to myself, “I am never going to be silent again.”

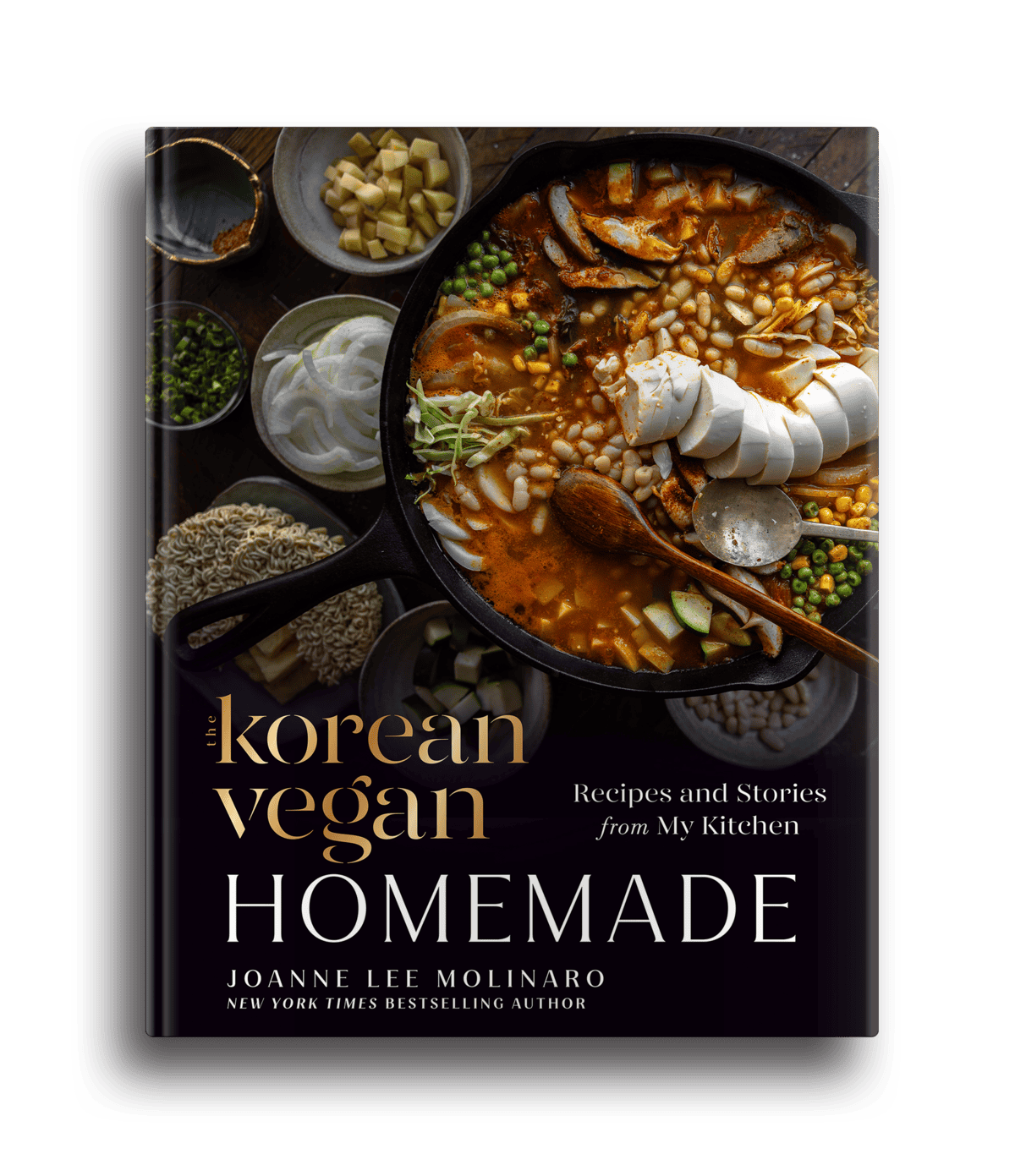

It’s been 15 years since that day at the Peninsula. Every time I go back—and I’ve gone back often (they have an excellent vegan tea service)—I think of that woman in the elevator. I think of her now, too, what she taught me in our brief exchange about collective pain, the human struggle, the necessity of allies and the sheer power of compassion, whose brilliance put Cartier to shame.

I think of my Hahlmuhnee. I think of the beads of sweat down my back.

I am never going to be silent again.

#blacklivesmatter

Beautiful essay. Thank you for sharing this story with us.