Kimchi and Cultural Appropriation in Food.

Read Ep. 31 | Show Notes

Subscribe Below to Receive the TKV Newsletter in Your Inbox

I remember the first time I wanted to invite Leah Granger, a blond, blue-eyed girl from third grade over to my house after school. I told Omma and, aside from ironing out the logistics (i.e., Leah taking the bus home with me and then having her mom pick her up before dinner), her biggest concern appeared to be, “but what about the kimchi?”

What about the kimchi…? I wanted to ask.

I soon discovered what she meant, though. Omma proceeded to move all the massive jars of kimchi out of the “main fridge” (in our kitchen) to the basement.

She was worried about the smell.

Prior to Leah Granger, I’d never “hosted” a non-Asian friend before and therefore, Omma never felt the need to rid the house of the prevailing smells of pickled vegetables, fermented soybean, and seaweed. By then, I was no stranger to the many differences between the “Lee Family Household” and the “Granger Family Household,” but till that moment, while watching Omma frantically displace the jars of kimchi that Hahlmuhnee had labored over, I’d never thought to be embarrassed of how my home smelled.

Of course, at the time, I thought Omma was being a bit of a lunatic. I couldn’t smell anything wrong with our home and I was certain that Leah wouldn’t either. But then, Omma told me about how often she’d heard complaints about the smell of kimchi from non-Asian colleagues. I would learn that my father’s peers also complained about his kimchi breath at work. And over a decade later, I would taste, firsthand, the many layers of my parents’ apprehension.

My sophomore year in college, I took Creative Writing 101. At the beginning of the semester, Professor “Mike” suggested that class might be more palatable if we each volunteered to bring something to eat, something to share with everyone else. Mostly, people brought bagels and donuts. Cookies. But, on my assigned week, I walked into that small classroom in the underbelly of the English Building carrying with me a tray still warm with freshly rolled kimbap. I smiled as I placed the trays in front of me because I was proud and excited to share the foods I knew so well with those who were less familiar with Korean cuisine. But before I could launch into the brief description I’d prepared in my head as I walked all the way from Dorcas (my favorite Korean eatery in Urbana) to campus while carefully handling the Styrofoam housing my culinary offering, I heard someone behind me go,

“Ugh!”

I turned around and saw one of my classmates covering his nose.

“What?” I asked, the smile I’d walked in with still frozen in place.

“God, the smell,” he answered.

He didn’t have any kimbap.

That was back in the late 90s. Years later, once Mario Batali introduced the many virtues of bibimbap on the Food Network, I assumed the world had changed. Famous chefs regularly butchered the pronunciation of “gochujang” (fermented chili paste) while adding it to their fancy menus and surprise, surprise–fitness influencers couldn’t stop talking about all the prebiotic health benefits of kimchi. YouTubers were going viral by trying every different flavor of Korean instant ramyun and for about 13 days, it seemed the entire world was making chapagetti, the popular instant noodle dish made famous by the Academy Award-winning Parasite.

Korean food was having its moment. And thus, despite my parents’ fears and my encounter with the rude idiot from my Creative Writing Class, I was, once more, truly excited to share with everyone my kimchi recipe–from start to finish.

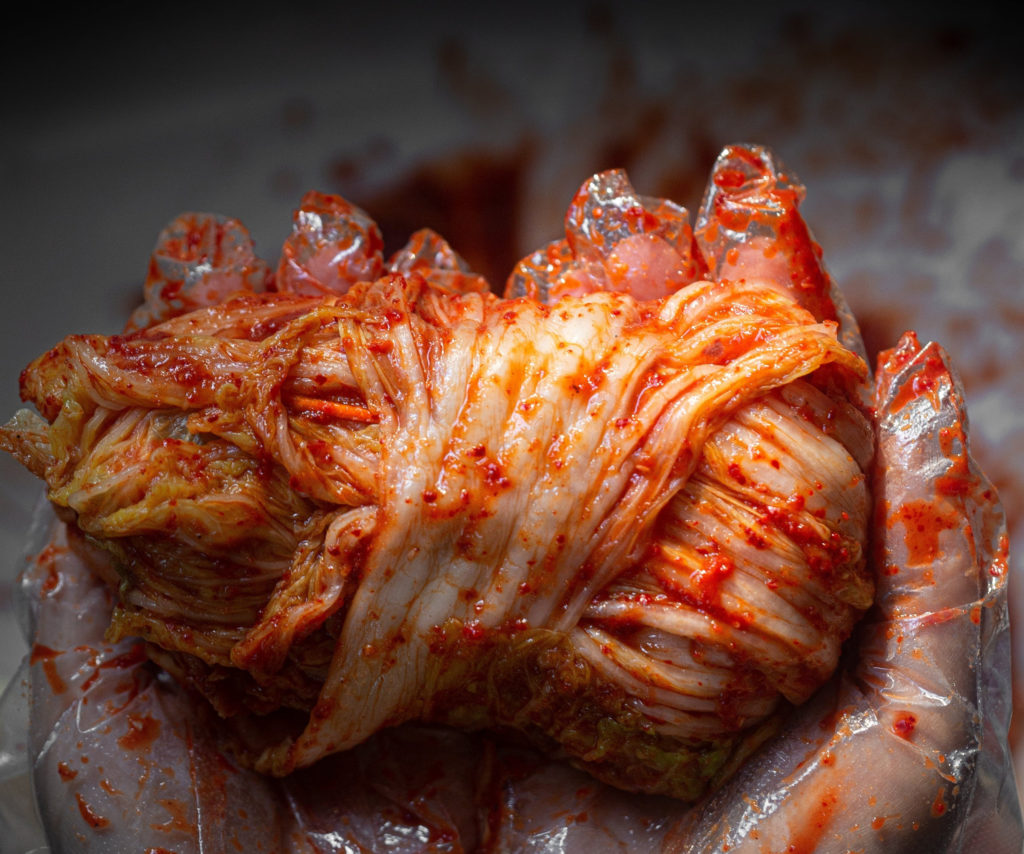

As I’ve written about before, there is probably nothing as quintessential to Korean cuisine and, in some ways, Korean identity as kimchi. Whether or not it’s what the rest of the world associates with Korea, it is undeniably what Koreans view as the icon of Korean food. Done properly, it will take hours to prepare, likely turning into a full day’s affair. Kimchi, a preserved vegetable, is meant to last throughout the winter months, when food no longer grows out of the ground. Therefore, you’re supposed to make a LOT OF IT. Think the meal prep of all meal preps–not just for the next few days, but for the next several weeks or months.

Not only will it take hours to prepare, kimchi making, or kimjang, will leave your quads, hamstrings, and glutes sore, as well as your hands a little tingly and red. Because, as I said, we’re not talking about salting, saucing, and jarring one lousy cabbage head. My mother bought 80 pounds of cabbage for just our supply of kimchi. When you’ve got that much cabbage involved, there isn’t a table large enough to accommodate all the massive bowls your cabbage will be “marinating” in; nor does it make sense to have your cabbage at chest level. Instead of hunching over a bowl of cabbage for hours, you want the leverage afforded by squatting (hence, the “kimchi squat”) as you press the salt into the tight cluster of yellow leaves and spread the scarlet sauce across each individual leaf. Given the amount of labor involved, is it any wonder that kimjang is often a community event that’s held outdoors, when the December frost and neighborly fellowship can serve as respite?

For members of the Korean diaspora, kimchi and everything we experience through kimchi–the work, the community, the spice, the smell, and even the shame–is wrapped up into who we are. Perhaps at one point in our lives, kimchi marked us as different in that vaguely dangerous way, but even before kimchi grew to be the new superfood, for many of us, kimchi eventually became a badge, one that granted us entry to a club of unspoken solidarity, pride, and, yes, power.

I dove head first into kimjang when I went vegan because a plant-based kimchi would be the most important barrier to hurdle in my “vegan experiment.” Having to choose between kimchi and veganism would otherwise place me in the untenable quandary of having to choose between my Koreanness and my values. I watched countless videos of old Korean ajummahs making multiple different kinds of kimchis. I consulted with my mother and her sister, my Eemo, to discuss how to optimize fermentation and flavor without fish sauce and shrimp paste. I developed numerous iterations of my own “fish sauce” to use in place of the non-vegan items I’d grown up with. In the end, though, it was when I worked with my Wehsoongmoh–my maternal uncle’s wife and still the undisputed “cook” of our family–to develop the recipe for my cookbook that I learned that the choreography of kimjang is as important to making good kimchi as the ingredients.

Why can’t I just cut the leaves with my knife? Isn’t that easier?

Because then you’ll damage the beautiful leaves hidden at the center of each cabbage head. That’s why you pull the heads apart instead of hacking away with a knife.

Why do we have to use our hands? Can’t we just sprinkle the salt over the cabbage leaves and toss? My hands are starting to burn…

Because you need to make sure the salt gets into the hardest to reach parts of the cabbage, where the leaves come together at the very end because you can feel it, right, Sunyoung? How the leaves are the hardest there? They need the most salt and you can only reach it with your hands.

Why can’t we just chop up the cabbage in advance and THEN stick them in a jar? We’re going to chop it up when it’s ripe anyway… We are wasting so much time rolling all of this cabbage!

Because when you roll up the cabbage just like this, Sunyoung, just like this–nice and tight–you’re creating pockets of air trapped between the leaves that will make your kimchi ferment the way it needs to if you want it to be delicious.

And lastly,

Where did you learn all this, Wehsoongmoh?

I learned by watching my mother. You know, she died when I was only a teenager. And I missed her so much, I would replay all the memories I had with her over and over in my head, just so I could feel near to her. And so many of my memories were of her teaching me to cook. Now I carry them with me.

In preparation for my book launch last summer, I wanted to make a video that showed everyone all the things I learned about kimchi, kimjang, and even my Wehsoongmoh. I hired a professional videographer to shoot a full recipe video; recruited my mother, aunts, and cousins to help make the kimchi, and even considered shooting the video outdoors on my parents’ patio (it turned out to be a little rainy, so we nixed that idea). Omma suggested we use her kitchen island to salt, sauce, and roll, and I looked at her like she was, once more, a lunatic.

“Why in God’s name would we do that?”

“Because…. Your followers. I don’t want them to see us making kimchi on the floor.”

“But we’ve always forever and ever made it on the floor. And besides, your island isn’t big enough.”

“Are you sure? They won’t think it’s…strange that we are making food on the floor?”

I waved her off. “No. We’re making it on the floor like we always make it. Doing it on the table is ridiculous and no one is going to make fun of us for doing it the way it’s supposed to be done.”

So, you can imagine my disappointment when over two decades after Creative Writing 101, I proudly posted a picture of my mother, my aunt, and me surrounding a massive silver bowl of newly sauced cabbage doing the “kimchi squat” and someone commented:

“On the floor? No thanks.”

My mother is 90 pounds, sopping wet. She has osteoporosis, autoimmune disorders, and sensitive skin. She is allergic to everything. As a newlywed, she nearly died from complications arising from her use of birth control pills (she was allergic). She has trouble chopping vegetables for japchae and mandoo because of her arthritis (but refuses to use the food processor I bought her). A couple years ago, she slipped and fell on the ice while walking with a friend and broke her wrist and her arm hasn’t been the same since.

But of all the things that make my mother frail, it’s the shame she has internalized over kimchi that inspires a wild fury in me. Not at her.

But at those who continue to reinforce her instinct to hide.

So, what does this have to do with cultural appropriation?

Before we get to that, perhaps we should define cultural appropriation:

The unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the customs, practices, ideas, etc. of one people or society by members of another and typically more dominant people or society. -Oxford Dictionary

While this definition is probably correct, it’s too vague to be of any real use. What does “unacknowledged or inappropriate” even mean? Are all “unacknowledged” adoptions of custom, practices, ideas of a different culture, per se “inappropriate?” Or, as some would have us believe, are all adoptions, period, of said customs, etc. unilaterally off the table (figuratively and literally)? Does there have to be some type of profiteering or other commercial incentive involved for it to be “appropriation” and is it possible, according to this definition, to misappropriate from a historically “dominant people or society?” And what the heck does “dominant people or society” mean?

Maybe it’s more useful to consider both ends of the appropriation spectrum. On the one hand, there are people who believe it is, per se, wrong to ever adopt the traditions of a culture that isn’t your own, even in the privacy of your own home or at your own event. For example, I saw a video on TikTok of a young white woman wearing a traditional Korean hanbok out of respect for her Korean in-laws. She got a lot of hate in the comments. On the other end of the spectrum are those who believe that “cultural appropriation” is merely a colloquialism of the woke leftist agenda, i.e., something that we just made up so we can collect on the boon of self-victimization.

Somewhere between those two extremes exists a reasonable and instinctively fair sounding description of what most people would probably agree is disrespectful or “rude.” But I think we need to unpack this a little more to understand that cultural appropriation–even in food–can result in far more than “hurt feelings.”

Let me give you a hypothetical.

Imagine your family owns a small bakery—one filled with all the delicious breads and cakes your grandma made when you were little. And imagine there is a chain bakery across the street—one that spends a good chunk of its 7-figure marketing budget telling everyone how strange and gross your bakery is. It hurts your feelings, sure, but worse than that, it hurts your business. Nevertheless, you stick to it and keep making and selling what you love. But then, a few years later, all of a sudden, the chain bakery starts making cheap, watered-down knock-off versions of the very same breads and cakes they used to claim were disgusting. And, because their budget is 1,000 times larger than yours while their costs are far smaller than yours (because, unlike you, they didn’t obtain the recipe from their grandmother, but rather cut and paste it from so-and-so’s food blog and thus, unlike you, they have zero problems with taking shortcuts to maximize their profit margin), they are able to outsell you, even though their breads and cakes don’t taste nearly as good as your own. Worse yet, now, because so many people are eating the knock-offs, they’ve been misled into thinking this “lesser version” is the way it SHOULD taste. Eventually, you can no longer keep up and as you shutter your shop and file for bankruptcy, you start to wonder, if I can’t compete with “chain made watered-down knock-offs” what’s going to happen in 10, 20, 50 years? Will grandma’s breads and cakes still even exist? Or will they get lost between big dollar budgets and the reach of those who have always had more, always had better?

This seems like an extreme example, I know. However, I think it adequately captures all the necessary elements of cultural misappropriation–i.e., the improper taking of something and not just the mere adoption of a practice that isn’t your own.

There is and must be space in the world for cultural appreciation, even in the form of adoption. The planet will change, the food growing out of it will change, and the people cooking in it will change. The adoption of and experimentation with different cultural cuisines is a critical component of not just ensuring we can still eat some versions of the foods we’ve loved, but that we continue to innovate more delicious food. How else can I, as a Korean American, create vegan versions of Korean food? How else can we, as a society, imprint the evolving progression of our values without trapping ourselves within the shackles of blind “tradition?”

This is why I add gochujang to my red sauce and use said red sauce to make tteokbokki.

And yet, I do get angry when I see someone thoughtlessly hacking away with their knife at a beautiful head of napa cabbage. I do get irate when someone comments on my recipe, “Oh, I just chop up all the cabbage in advance–the way she does it is a waste of time.” And yes, it chaps my hide when I see the same folks who would have turned their nose up at kimchi 30 years ago selling their “you can use paprika instead of gochugaru kimchi” recipe because it’s now cool to eat this thing called “kimchi.” So much gets lost with the mass proliferation of cultural cuisine when neophytes masquerade as experts, when food-bloggers or celebrity chefs leverage the patina of authority afforded them by large followings or crowded restaurants, who have no problem sacrificing other people’s stories to make their food more profitable, more palatable to the “majority,” the one addicted to TL;DR content (Too Long: Didn’t Read), the one that still believes in its heart of hearts that the “right way” to do things is the way they’ve always done them, the way “most people” have always done them: you cook on the table; you use utensils instead of your hands; and if it smells different, it smells wrong.

I don’t care what you make in your kitchen. I also don’t care if you mix and match and try new things, and I also don’t particularly care whether something is “authentic” or not. Cultural appropriation, i.e., when certain persons or groups leverage their privilege to profit off the sale of someone else’s culture without so much as acknowledging it—results in less delicious food.

And yes, there is a sort of violence in this mindless pursuit of profit, one that perpetuates my mother’s shame, that covers my Wehsoongmoh’s soft body in the heavy cloak of silence, that flattens me against the familiar fangs of disappointment when I’m told, in so many words,

“Sorry. Can you please make yourself even smaller to make us more comfortable?”

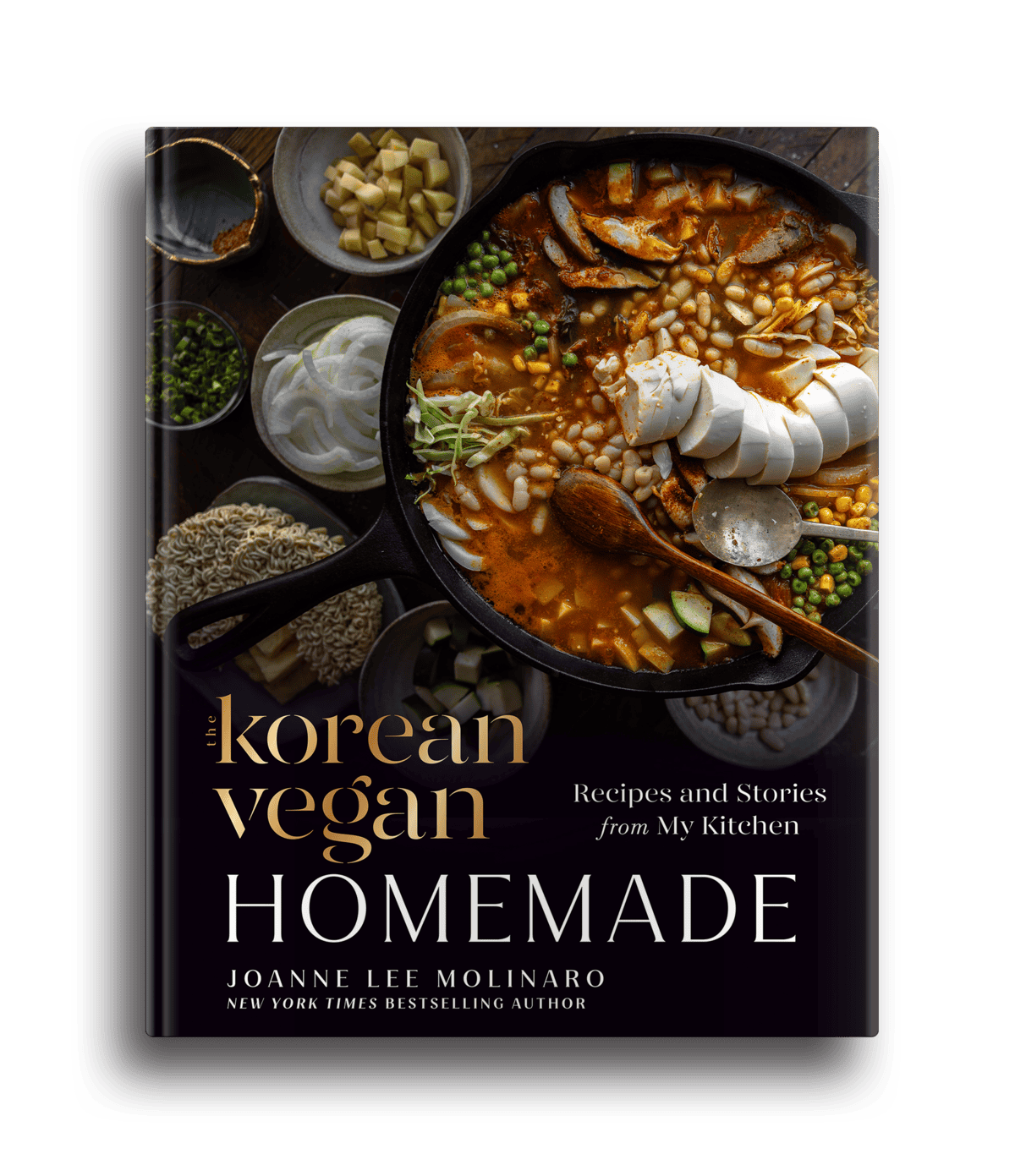

THE KOREAN VEGAN COOKBOOK IS 50% OFF!!!

So, I totally don’t blame you if you’re wiping drool from your face after staring at all the photos! LOL. Do yourself a favor and pick up a copy now because it’s currently on sale for $18!!! That’s 50% off!! If you already have a copy, grab one (or three) for your friends, colleagues, neighbors, family members–my sister-in-law made me sign 3 books the last time I was at her house because she’s giving them to all of my nephew’s teachers!

Ask Joanne

Joanne,

What are the best vegan spots in Seoul? What are some accidentally vegan dishes in Korean cuisine? so I can order it in Seoul :))) -Simona

Simona, I’m so jealous you are going to Korea!! The last time I was there was in 2019, and man oh man, do I miss it! Here are some vegan spots that I enjoyed immensely on my last trip there that I think you will just LOVE:

- Shin Dong Yang Deh Ban Jum: This is one of those hole in the wall Chinese restaurants that might seem a little sketchy but then knocks your socks off with the best Chinese-Korean food you ever ate. They have two menus–one vegan and one not vegan. I ordered jjajangmyeon and I actually sent it back because I thought they made a mistake and sent me the non-vegan version. IT WAS THAT GOOD. Their recipe is what inspired my own jjajangmyeon recipe in my cookbook. This place is hands down my FAVORITE restaurant in Korea.

- Bread Blue: Towards the end of my trip, I basically planned my entire day around finding a nearby Bread Blue to stock up on more vegan Korean pastries. There weren’t a lot of them, but there were enough throughout Seoul where I could always cab it there before going to bed at night. The bread, cakes, and other goodies are phenomenal and their entire menu is vegan, which is a relief because Korean bakeries traditionally have NO vegan items (even bread has butter and eggs in them).

- Maru: I love Korean street food, but it is HARD to find vegan Korean street food. Maru is an entirely vegan shop in Insadong’s shopping district that boasts a menu featuring the most popular Korean street foods: tteokbokki, kimbap, o-deng. It’s tucked away and a little hard to find, but don’t give up–it’s worth the trouble!

- Han Gwa Chae: Korean vegan buffet YASSSSSSS!!! This is kind of like Korean temple food meets cafeteria food. I know, that doesn’t sound great, but it’s like a more accessible version of temple food (which is EXTREMELY refined and fancy). The restaurant is below ground (you need to take a flight of stairs down) and you grab a tray, add whatever you like to it, find a seat at one of the communal tables, and eat to your heart’s content! I loved this place so so much!

- Plant Cafe Seoul: If you’re craving a vegan burger, milk shake, or a slice of cake, while you’re in Korea, then Plant Cafe has got you covered! With two locations and a fun menu with a variety of selections, you’ll feel right at home (away from home) here!

As to your second question, I’ve got bad news for you: while Korean food is easily veganizable, the overwhelming majority of Korean food is not vegan. I know–it’s a little counterintuitive because Korean food is so vegetable centric! But, they are a peninsula, and as such, Korean cuisine relies heavily on fermentation through fish sauce or shrimp paste. Moreover, as I mentioned, for some reason, Korean European-style bakeries (like Paris Baguette or Tous les Jours) inject dairy and eggs into everything, even a loaf of wheat bread.

That said, as Korea grows ever more “vegan friendly,” you may want to zero in on the following:

- Korean temple cuisine. There are a lot of temples that now have restaurants at which you can sample their creations. Korean temple food is largely plant-based and eschews animal products. Chaegeundam and Balwoo are two spots in Seoul that offer beautiful temple cuisine.

- Tteok or Ricecakes. These Korean desserts, which you can find at a traditional Korean bakery (not the new fangled Korean European ones) or fancy department stores are usually vegan and gluten free. You will certainly find a variety of vegan options. Korean rice cakes are chewy, dense, and far less sweet than American desserts.

- Bibimbap. Although bibimbap isn’t what most Koreans will order at a restaurant, it’s one of the few items on a Korean menu that might be veganizable. I say “might” because there’s still a good chance that the banchan (i.e., the vegetables) they use to make bibimbap has been seasoned with fish sauce. Assuming their banchans are vegan, you can always ask them to omit the meat (or sub in tofu) and fried egg. I know for a fact that the restaurant inside the Four Seasons Seoul makes a vegan bibimbap!

- Tofu Stew. There are a lot of tofu houses in Seoul–eateries that specialize in dishes created with the versatile soybean based protein. However, many of them will include meat and other animal products in their recipes. You will likely have better luck, however, at finding vegan options at a tofu house than at most other restaurants in Seoul. Again, in addition to asking them to remove all obvious animal products (e.g., meat, eggs), make sure their broth isn’t made with anchovies and that their veggies aren’t seasoned with fish sauce.

Obviously, all of the above applies to Korean restaurants here in the United States, as well (which is why I really need to come up with my own restaurant). I wish I had more options for you, Simona, but hopefully, the above will give you a good start! Safe travels!

Wishing you all the best.

Updates/Random Things.

- Andiamo a Roma!!: Yup! In a few days, Anthony and I will get on a plane destined for Rome, Italy! Anthony has a lot of family in Rome and I am so looking forward to seeing miei cugini Italiani. We’ll be staying at an AirBNB for the most part so I can cook out there and MAN OH MAN am I looking forward to some Italian vegetables!

- What I’m Watching: This past week, Anthony and I immersed ourselves in a true crime docudrama called The Staircase. It’s based upon the real life murder mystery involving Michael Peterson (the alleged killer) and his wife, Kathleen (the murder victim). I vaguely remember hearing about this in the news back when it all went down (2001), but the series was incredibly gripping. The performances by Colin Firth and Toni Colette were excellent and with only 8 episodes, it was a relatively low lift from beginning to end. If you like true crime, this one’s for you.

- Holiday Gift Guide: I received so many lovely emails in response to my first ever Holiday Gift Guide! I am so glad that you all have found it useful. In case you don’t want to dig through your inbox for it, you can find it here. Make sure to bookmark it for future reference!

- What I’m Cooking: In case you haven’t guessed it already…I’m making kimchi!! You can find the full kimchi recipe from the cookbook here!

Parting Thoughts.

Yesterday, I bonked.

I was scheduled to run 14 miles, the longest distance I would have run since February, to cap off my biggest week of mileage since I started running again after recovering from injury earlier this year. But, between two consecutive nights of sub-optimal sleep and a reckless miscalculation of the necessary pre-run calories, it wasn’t in the cards. By mile 10, I could no longer ignore the gnawing in my stomach that started back at mile 3 and I knew that the dates I’d stuffed into the back pocket of my shorts weren’t going to cut it. By mile 11, pumping legs transformed into churning cement and I finally pulled over, leaned against a stump of wood along the beach, and focused on not vomiting. I texted Anthony, who was supposed to meet me when I finished, that I’d be wrapping up a little earlier than planned.

I sometimes make the mistake of tying my value as a runner, athlete, even human to whether or not I successfully complete all the miles in the excel spreadsheet that constitutes my “training plan.” Whether it’s the swagger that attends the culmination of a tough workout, grueling long run, or a grinding week of mileage, OR the self-flagellation that ensues the instant I step off that path so much as .1 mile early, removing my ego from the process can sometimes be challenging. This isn’t surprising, I guess. It takes some level of ego–a “fake it till ya make it” attitude–to push past the boundaries we create for ourselves, to believe we can actually do things that are really really hard.

But our ability to do “really really hard things” is neither limitless nor, more significantly, linear.

I follow this runner on Instagram who has made herself famous by posting hilarious videos of her running outfits, thoughts from the corn-ridged roads of somewhere in rural America, and her many misadventures with yoga. She is an endless source of quirky run-spiration, effectively deploying self-deprecation to prove that running isn’t exclusively reserved for track stars, fitness models, and influencers. She posted a short video while walking during a Turkey Trot, proclaiming that instead of “stay[ing] hard” a la David Goggins, she was going to “stay turkey.” But yesterday, she posted a video that was a little different from the usual fare. The typical irony in her voice was still present, but it was weighed down with something that resembled fatigue: “Congratulations. We made it through the week…” In her caption, she revealed the source of some of her weariness: “I battled ?️ ?️ some seasonal sadness and zero motivation but forced myself to three yoga classes and stuck to my training.”

Our ability to show up–for our family, our friends, and, most importantly, ourselves–is a direct function of training and reserving for life’s most formidable tests, i.e., knowing when we can push ourselves a little bit more and knowing when we need to pull back, cut our run short, and “stay turkey.” While there can definitely be something empowering about “staying hard” and sticking to a training schedule even while struggling with the ennui that sometimes materializes out of the blue (or not so out of the blue), it’s important to guard against devaluing ourselves when we “fail” to meet our goals because of a sudden onset of inexplicable sadness, grief, or burnout–not because we’re “weak,” but because we’re smart.

After all, we don’t take one step in front of the other simply to walk or run, but to get to a finish line. What good is any of it if we arrive at that finish line having burnt through the capacity to celebrate it?

As I jogged up the hill to the grassy knoll that promised the end of an “incomplete” long run, I spied Anthony about 30 yards ahead, taking pictures of the ocean. It occurred to me, then, that this was the weekend he was supposed to have run the California International Marathon. He’d dropped out a couple weeks ago after several weeks of unaccountable levels of fatigue during his runs. Thus, instead of flying to Sacramento for his first marathon in nearly three years after six months of dedicated training, he drove me all the way to Santa Barbara, hung out alone at a random cafe for 2+ hours, and then spent 20 minute standing in the soft mist to make sure he could wrap me in a huge towel as soon as I hit 13.0 miles. In that moment, I decided that instead of spending the day feeling bad about bonking, I was going to eat some pasta and sourdough with the man I loved.

Sometimes, it isn’t so much about where the finish line is at, but the person you are when you cross it.

– Joanne