Father-Daughter Relationships.

Read Ep. 23 | Show Notes

Subscribe Below to Receive the TKV Newsletter in Your Inbox

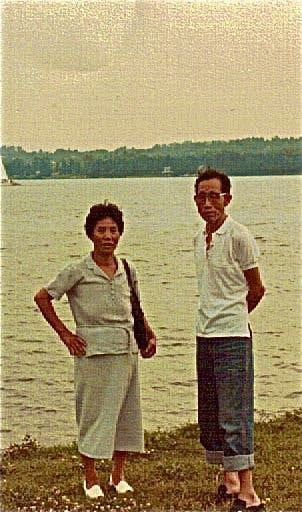

On the morning of June 25, 1950, North Korean forces began shelling the westernmost tip of the 38th parallel. Ongjin, a peninsula shaped like a craggy hand darting south into the Yellow Sea, was technically below the parallel, and therefore, should have been safely outside the reach of the Korean People’s Army–what the North Korean military called itself. But, the KPA was determined to collect Kangryong, a small gem wedged between two stubby fingers of the peninsula. And thus, a crimson flare cut through the moonlit sky shrouding the squat homes scattered across the tiny villages along the jagged southern edge of Ongjin. And the people of Ongjin, known best for their medicinal teas and ability to withstand long hours in the region’s iron rich mines, woke up to a hailstorm of artillery and the grating vibration of Soviet tanks.

My mother was one of them.

She was less than a year old.

Amid the chaos, my grandparents heard that the promise of safety lay along the coast, and so they set out on foot with whatever they could carry, towards the Sea, leaving behind thick columns of smoke. With two infants to carry, very little water and food, my grandparents took several days to find their way to the beach. Sure enough, they were met with the broad hull of a ship marked with letters they couldn’t read, the pandemonium of words they’d never heard before, the crushing roar of an angry tide as the Sea hurled itself at the crowded shore. In my grandmother’s arms, an infant, shrieking with hunger, caused no one to bat an eye.

No one who spoke Korean could tell them where the ship was headed.

No one who spoke Korean could tell them how long it would take to get to their final destination.

No one who spoke Korean could tell them whether there was any food and water on board.

So, my grandparents let themselves be herded onto the deck, and without knowing for how much longer they’d be forced to watch their daughter starve to death, they concluded that the most loving thing they could do for her was to end her suffering, to end her life.

As the ship eventually pulled away from the only home they’d ever known, my grandparents climbed up to the uppermost deck, where there were far fewer people. They carried my mother towards the rail, peered down at the cold black water dozens of feet below them. My grandfather began to pry my mother from my grandmother’s arms, but Hahlmuhnee wasn’t quite ready to do this thing they’d agreed to do, however sensible it sounded when her husband explained the alternative. She pulled her girl closer to her, pressed the rough side of her face to her baby’s, until she was convulsing as violently as her daughter.

The commotion drew notice. Two soldiers garbed in dark fatigues, their rifles slung over their shoulders, approached. Perhaps they wanted to help. Perhaps they wanted the small family to step away from the rail. Perhaps they were merely curious. It didn’t really matter, since they couldn’t say anything my grandparents would ever understand.

It is up for debate whether there existed words in any language that could adequately describe my grandparents’ anguish and fear. But, again, it didn’t matter, since they didn’t speak the one language that would make an impression.

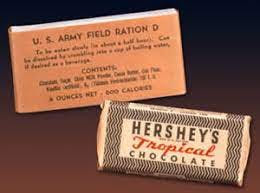

A fresh wave of wails pealed from my mother’s angry red mouth. Maybe there is something primal about a hungry baby, a pitch to starvation that is so singularly universal that it transcends speech, it obviates the need for words. One of the GIs reached into the deep pockets of his uniform and pulled out a bar wrapped in dark paper, glittering with Roman letters:

“H – E – R – S – H – E – Y.”

Nearly three decades later, Omma would tell me:

“That Hershey bar saved my life.”

She spoke in perfect American English.

4,200 years earlier…

Over 4,000 years before my grandparents nearly killed my mother, a similarly chaotic scene broke out in Babylon, the capital city of the Empire of Babylonia. The Babylonians were determined to erect a tower, one that would reach into the heavens and protect them in the case of another Great Flood. But this angered God, who viewed the Babylonian’s innovation as an act of defiance. He struck down the tower before it was completed, and he cursed them all with different tongues. Thus, though everyone woke up that morning speaking the same language, they went to bed that night not being able to understand their neighbors, their friends, maybe even their children.

According to the Bible, this is why my mother nearly died before she turned one.

And why my parents and I have struggled to see eye to eye our entire lives.

The Dominick’s Language.

The first language I remember speaking belonged to my grandmothers. We called my maternal grandmother “Seoul Hahlmuhnee” when my father’s mother came to live with us (so we could distinguish the two grandmothers), because my mother’s family ultimately ended up in Seoul. Seoul Hahlmuhnee was my first playmate, my first best friend, my first everything, and therefore, it only made sense that she would gift me with all my first words:

“Uhm-ma” for mother.

“Ha-moh-nee” for grandmother.

“Ba-nah-nah” for banana.

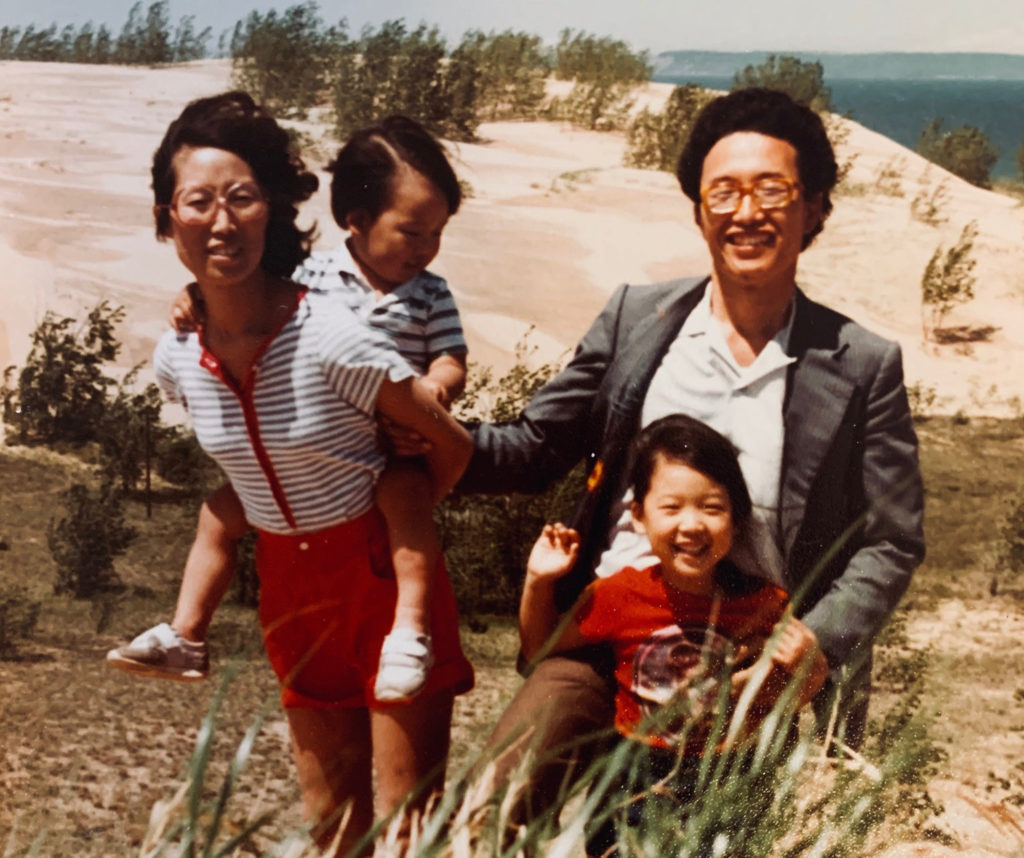

My parents, too, spoke only Korean inside our home, and therefore, for the first three years of my life, I spoke what my mom describes now as “beautiful Korean,” learning to build bridges effortlessly between myself and the only others in my life that made any difference–my grandmother, grandfather, mother, father, and aunty (my brother hadn’t arrived on the scene yet).

But, even then, I was aware of a broader world, one that bustled to life outside the door of our apartment building in Ravenswood. It had its own language, the one my father used at the grocery store–Dominick’s. The lady at the cash register would offer these words to my father and, amazingly, he would hand a few back, together with a small rectangular note that he would rip out of what looked like a leather bound book. On it, he would write something, his hand darting across the pale blue paper with hesitation, as if he had to think, first, before committing the ink to the complicated set of loops and crosses and dots that, I would learn later, spelled his name.

I called this “Dominick’s mahl” or the “Dominick’s talk.”

It was the same language they used inside the TV when Hahlmuhnee and I watched Sesame Street or The A-Team, but it was hardly relevant to me. I never had to speak with the cash register lady at Dominick’s or the children on Sesame Street or the scary looking man with the mohawk and tattoos, “Mee-stuh Tee.”

And then, my very own parents decided it was time to erect the Tower of Babel in our quiet little home in Skokie, Illinois.

They sent me to school.

What is “Real” Anyway?

I soon discovered that everyone, including the bus driver, Teacher, and all the other students spoke the Dominick’s language and that I was the only one who didn’t. That first day was an awakening, of sorts, a lesson in not just the ABCs, but in the world’s apathy to what occurred inside the screen door of our Skokie house. They didn’t care that inside our home, we only spoke Korean. They didn’t care that at our kitchen table, we ate kimchi and rice and fried seaweed, and therefore, that’s what my Hahlmuhnee packed for lunch that day. They didn’t care that Hahlmuhnee picked out the sohknehbok (thermal underwear) I was forced to wear underneath my long-sleeved shirt and corduroys. Instead, they pointed at me, gestured at the flowered bit of fabric peeking out from beneath my pants as I tied my shoes just the way Hahlmuhnee taught me, and they laughed. The explanation was so simple: “Hahlmuhnee made me wear these! Hahlmuhnee made me this food! Hahlmuhnee never taught me the Dominick’s language!” But the words–they were like pebbles filling my mouth.

Unfamiliar, cold, indifferent.

I spit all of them out when I got home, though, at the one who had failed to prepare me in every way that mattered for that first full day outside the screen door. At Hahlmuhnee.

But they were only pebbles, then, and my grandmother was a mountain. My anger would dissipate with a plate of food, a bowl of snacks, an episode of Sesame Street. Hahlmuhnee would then take me to the park around the block and we’d swing as high and as fast as we could while she told me stories about growing up in a home that I assumed looked just like ours, with a park that looked just like mine, with a swing set that would carry her as close to heaven as she taught me to climb.

Luckily, the Dominick’s language came easily to me. Within a couple weeks, I made friends with the very same girl who’d laughed at my sohknehbok. Her name was Leah. Teacher was nice to me, if a little scary, still, with her big red toenails and pink lipstick, and, eventually, Hahlmuhnee even started packing ham sandwiches and Frito Lays in my Cabbage Patch Kids lunchbox. One day, we were tasked with bringing something for show and tell, so I brought my little een-young, a doll Omma gifted me with so long ago I couldn’t ever remember being without her. She had chestnut brown hair in pigtails, curling eyelashes, and large brown eyes that shut closed when you lay her down for bed. At home, she was my constant companion, my fingerprints tattooed all over her legs and arms and face until she was so dirty, Omma threatened to throw her away. But I wouldn’t stand for it. So, when Teacher told us to bring something for show-and-tell, I knew I had to show and tell everyone about my very best friend.

Only, when I showed her to Leah, she laughed again and used a word I didn’t understand: “But she’s not ‘real.'”

I’d never heard the word “real” before, but I could understand the contempt that Leah injected into it, plainly enough. Whatever “real” meant, it was something I wanted my doll to be.

So, I got up in front of my entire kindergarten class, in front of Teacher, shook my dolly’s body in front of them all until her little head popped off as I declared,

“Oh, but she is real.”

Days later, I would learn what “real” meant.

And wonder if Teacher and all my classmates thought I’d lost my mind during show-and-tell.

The Isolation of Babel.

According to the legend of Babel, God struck down the tower and created multiple languages to foment confusion. In the same fashion, my exposure to English caused a massive shift in our home life. Academic excellence now depended upon my ability to speak the Dominick’s language, and therefore, my parents encouraged me to speak English at home, calling me by my American name–“Joanne”–instead of Sunyoung, the first name I ever knew. Maybe they never stopped to think about how quickly Korean would leak out the other side, but in just a couple years, a wedge grew between English-speaking Joanne and my Korean-speaking Hahlmuhnees. Losing that closeness with my grandmothers was, perhaps, inevitable. But still, it was like I’d run away from home and forgot the way back.

That wedge existed between myself and my father, as well. Though Daddy was very proficient in English (he studied English Lit at Yonsei and was the one who first introduced me to English, after all), he had a very thick accent, one that differentiated him from the fathers on TV or those I’d see talking so easily with Teacher at school when they came to pick up their sons and daughters. Omma, on the other hand, was different. She not only spoke English perfectly (in my view), but she did so just like Teacher, just like the other mothers, the ones with their curly blond hair and Press On Lee nails.

As demonstrated by my mother’s own origin story, language barriers can have catastrophic, possibly even life or death, implications. (See also Becker’s Hospital Review, “Language barrier may be a higher indicator of COVID-19 mortality than race.“) [Indeed, as I write this newsletter, my mom is anxiously texting me about a friend who recently lost her husband and is in desperate need of a Vietnamese speaking trust and estates lawyer in Chicago. I literally know not a one.] But, language barriers at home may also create their own brand of chaos. Multilingual households are not, necessarily, disruptive. It’s the lack of co-fluency that may, however, have unintended consequences. According to one study,

parents and children who do not share fluency in English experience “dissonant acculturation.” According to the theory, possible consequences of dissonant acculturation include decreased parent–child communication, role reversal (e.g., loss of parental authority), and increased parent–child conflict. These consequences, in turn, place children at heightened risk for social and academic problems.

I hardly ever spoke to my father. Now, part of this was because my dad, as I’ve alluded to before, was aloof and seemingly uninterested in his children (which is not entirely atypical of Asian immigrant fathers). But some of it was definitely because even when we did speak, it was frustrating. As my vocabulary continued to outstrip his, I could never tell whether my words landed anywhere with him, and on multiple occasions, his accent was so thick, even I had trouble discerning what he meant. Communication for anything beyond the basics–“come pick me up at the side entrance at 6” or “my piano lesson got moved to 7 today” or “please stop eating my French fries”–seemed utterly pointless. I never discussed things like art, music, or politics with my Dad even though he loved music, could draw the most beautiful sketches of our backyard, and yelled at the news almost every single night. And I certainly never bothered to detail the innermost workings of my heart–without having any confidence that the most precious parts of me would actually be understood, much less valued. It seemed safer this way.

One of the most vivid dreams I’ve ever had in my life was about my Dad. We were in the living room of our Skokie house. I can still see the soft shag carpeting my mother picked out; the ugly brown coffee table that Daddy used to study at when he was trying to get a job at the post office. Daddy was in his pajamas–a white t-shirt and white shorts. I was maybe 4 or 5 years old and he hoisted me up onto his shoulders, something I couldn’t remember him doing in real life. I instantly realized, in that way you just know things in dreams, that our Skokie house had been infiltrated by monsters, that even though I couldn’t see them yet, they would descend upon me and Daddy and overtake us. And it was for this reason that Daddy carried me on his shoulders.

But I didn’t feel safe.

I knew my father couldn’t carry me for very long and sure enough, his grip on me began to falter and I started to slip off his back. I bent my knees, trying desperately to prevent my feet from touching the carpeting, as if it had somehow transformed into a sheet of broken glass. Even as I cleaved to my father’s small back, I knew that eventually, I would have to carry him, that it would be up to me to make sure his feet never touched the ground, as I figured out a way to escape, because the monsters were coming. The monsters were here.

But I’m too small to carry Daddy, I said to myself, before waking up.

The Most Hated Typewriter in the World.

When I was in 4th grade, my father lugged an ugly, green typewriter into my bedroom. He handed me a small bottle of white out, along with a fistful of papers.

“Here, you type this,” he said.

The papers contained his handwriting–every single letter perfectly slanted at 45°, every loop uniformly shaped, every cross a perfect hash. But even so, I could see evidence of his hesitation, the way his hand would hover over an empty space for a second or two before he finally pressed the nib of his pen to paper. What was Daddy writing that was so important he’d need it typed up?

It turned out he was writing grievance letters to the union boss at work (US Postal service). Though I had never used a typewriter before, Daddy gave me a quick run through: “here’s the switch to turn it on,” “here’s how you roll the paper into it,” and “here’s what you do when you make a mistake.” He then left me alone, and I spent the next few hours typing out a single letter, in which my father detailed how much his back was hurting from all the manual labor required of him at the post office.

Over the years, I wrote enough letters to fill a book, and in so doing, I not only became very good at typing letters, I grew intimately familiar with things my father never actually talked to me about–how much he hated his job. How hard it was working in an environment that seemed intent on misunderstanding him, treating him as second class, or otherwise dismissing the injuries he sustained while working the night shift. Once, when I ran out of white out, I went to the old, wooden desk he kept in the family room. Rummaging through the the top drawer, I found a roll of stamps, a couple rubber thumb guards, a letter opener that he would wear on his finger like a ring, and breath mints. I knew, from reading his letters, that his colleagues often complained about his kimchi breath.

I grew to hate the sight of my father’s shadow outside my door, a sheaf of papers in his hand. Sure, part of it was because I was a bratty, spoiled child, but it was also because I dreaded the helpless rage I would inevitably sink into like quicksand every single time I had to read his words. With every letter, Daddy brought with him the sharp, biting wind of the world outside of our home, one that smelled feral and viciously dispassionate. As I grew older, I silently corrected his grammar, replaced his syntax with more “official sounding” verbiage. I liked to think, even back then, that those who might assume my thick-accented father was defenseless, dim-witted, or slow would find me on the other end of that assumption.

Sometimes, I made sure it happened. When I heard my father struggling with customer service, the insurance company, the bank–I’d take the phone from him and say, “This is his daughter and yes, I have his consent to talk on his behalf,” just to make sure they knew who they were dealing with. Sometimes, they were relieved. Other times, they grew defensive.

It wasn’t a role I asked for–it was literally shoved into my lap with a stack of papers. And I would be lying if I said there wasn’t some part of me that resented my father for putting me in this position, that wondered what it would it might be like to have a Dad like the ones on TV or in the movies we liked to watch together–

The kind that could carry you, without ever letting your feet touch the ground.

“You People Are Ruining the Neighborhood.”

I was walking my dog one night. I lived in a townhouse complex and though our homes were essentially cheek to jowl, I didn’t know many of my neighbors. I tried, however, to be polite, to stay out of anyone’s way, to not be that neighbor (you know what I mean). So, on that evening, when I saw a short, blond woman carrying a big box emerge from the door next to my house and begin walking towards me on the sidewalk that connected our homes, I stepped onto the lawn and pulled my dog with me to get out of her way and mumbled, “sorry about that,” as she passed. And just as she swept past my shoulder, I heard her mutter, “Yeah, I’ll give you something to be sorry about.”

It reminded me of the time this girl in homeroom called me a “stubby legged bitch” while walking behind me with her friends on the way to gym. I could hear her, and I knew she wanted me to hear her, in fact, that she wanted me to turn around and start something I knew I’d regret right then and there in the bowels of New Trier High School. So, on that day, despite the burn that flowered inside my belly, I kept walking on my stubby legs, all the way to gym class, pretending I couldn’t hear a thing.

But on that night, with my dog Billy by my side, I turned on my heel and stated quite crisply,

“Excuse me? Do you have a problem?”

The petite blond woman turned around, marched towards me, and said,

“Yeah, I’ve got a problem. You people are ruining the neighborhood.”

By definition, “You people” couldn’t refer to just me–I was by myself, after all. It wasn’t my first rodeo, though. I’d heard references to “my people” throughout my life, on the playground, in the classroom, at the office. She was talking about my mom and my dad, who also lived in the townhouse complex. The Korean American family that moved in just across the way from us. The other Korean family that lived by my parents. She continued her indictment of “my people” by explaining that all the Koreans in our neighborhood were rude and antisocial, including “your father.” It never occurred to me to ask her when or how she’d encountered my parents or how she even knew they were related to me. All I could think of was my Dad, his broken English, his tendency to avoid interactions with Americans–not because he was unkind or unfriendly, but because he was embarrassed or conditioned after nearly three decades of colleagues who othered him to believe that life was simply easier when you kept out of their way.

I stood there, rooted to the pavement that joined our homes, and looked her squarely in the face as I said, “What a racist thing to say,” knowing that had she lashed out at my parents directly, they probably wouldn’t have even understood what “you people” meant and that even if they did, they may not have known how to respond.

At some point, I had not only become my father’s typist, proofreader, and sometimes translator.

I had become his voice.

English Speaking Swords.

In 2021, the US saw a 164% surge in hate crimes against people of Asian descent. At first, I sat on the sidelines, quietly observing the media’s coverage of what was happening to Asian Americans. I wondered whether it might be in response to COVID, the rhetoric embodied by the phrase “China virus.” I grew concerned at the number of elderly Asians that seemed to be targeted, started to dread seeing another mutilated face that looked a bit like my father’s as I scrolled through the news each morning. And then, on March 16, 2021, a man walked into a Korean-owned massage parlor and slaughtered eight people, including 6 Asian American women.

And the first thing I thought of was my mom and my dad.

What if one day it was my dad who came home with blood all over his face, his teeth knocked out of his mouth? What if it was my mom–my 90 lb mom–who was discovered with over 40 stab wounds inside her home? What could I possibly do to prevent this? I called Omma, suggested she pick up some pepper spray for herself and Daddy, and she laughed nervously.

“Omma, this isn’t funny. People are dying,” I implored.

For all her American savvy, my mom couldn’t recognize the danger of racism, that people were dying because of the ever prevailing instinct to dehumanize someone who has a thick accent, smelly food, or the wrong colored skin. Because it’s so much easier to inject inferiority into difference than to face our fears. Because it’s so much easier to destroy something instead of someone.

As I watched the continued coverage of the Atlanta shootings, I repeated the words I said to myself all those years ago in my sleep:

But I’m too small…

The following day, when it became clear that some wanted to change the story, so that it would no longer be about the Asian women who were objectified, dehumanized, and murdered, but about a young white man who had “a bad day,” I knew that the answer wasn’t arming my parents with pepper spray or even a gun.

I thought about all the letters that my Dad made me type up for him when I was barely old enough to spell, all the times I had to use my “professional voice” with customer service when I was only in junior high, how quickly I had to learn how to read a bank statement or claim adjustment form because my parents needed help understanding them. Yes, it was true that my father and I weren’t close, that I’d literally never had a voluntary heart-to-heart with him in my entire life, that there were times when I hated having to be his translator. But as the brutalization of Asian immigrants continued to skyrocket, it seemed that all of these moments specifically equipped me for this challenge, that my parents needed me to brandish my English words like swords, not just to defend them but to reveal them, to throw off the cloak the world had thrown over them in its rush to hide all the things that made them different, and, at the same time, the things that made them human–their struggles, their pain, their grief; to take everything I’d ever felt, everything I’d learned about being different, about having to translate not just those letters but the entire fucking world for them.

And make them safe.

Ask Joanne

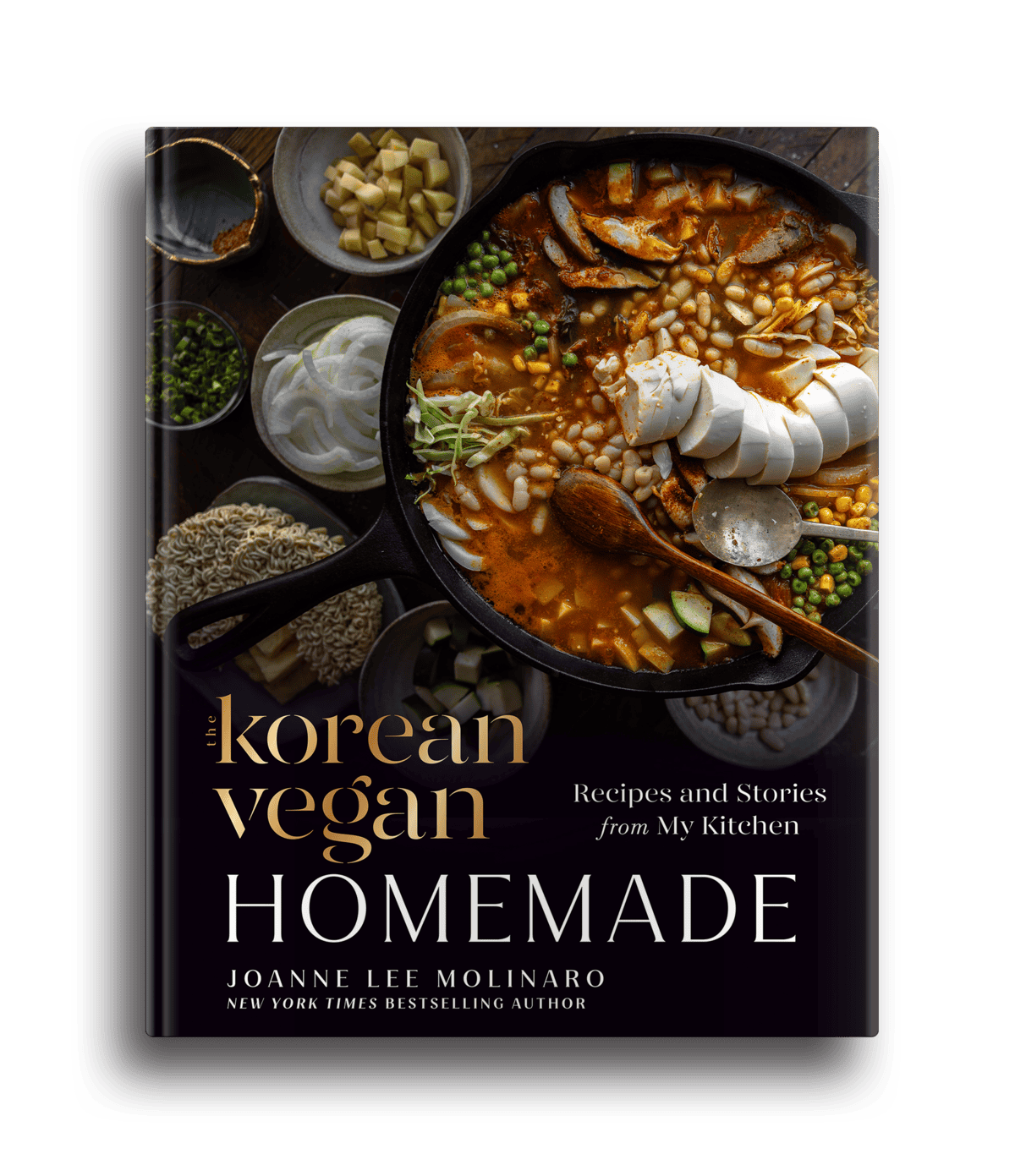

Joanne, I have been following your journey since I accidentally found you on Insta and then I was hooked on your stories and I had to get your book. I was lucky enough to meet you in person and get a signed copy. I plan to use your recipes during our vegan thanksgiving this year. You truly are a kind soul. My question to you is when did you discover you had a passion of cooking and what is one of your favorite dishes you made in the beginning days of vegan cooking. -Vegan Accountant

Greetings, Vegan Accountant!

Thank you so much for the very kind words and so happy to hear that you are a part of the TKV community. I am especially thrilled to hear you plan on using my recipes for Thanksgiving! SPOILER ALERT: I’ve been workin’ on a few new recipes for the holidays that I can’t wait to share with everyone! Stay tuned for more on that!

As to your question–when I discovered my passion for cooking, the answer is simple: when I went vegan. Before then, I viewed cooking as something you did to impress your parents or your boyfriend. I hardly ever cooked. I was a full-time lawyer and during my first marriage, my husband was totally content with McDonald’s, Taco Bell, and Popeye’s. And, to be honest, so was I. If anything, we bonded over our mutual love of fast food. Even after my divorce, though, I preferred takeout to cooking, mostly because I viewed it as a hassle, especially if mine was the only mouth to feed.

But then… when I went vegan, takeout was no longer a real option for me. Not only were there almost no vegan items on menus back then (unless you count French fries and dressing-less salads), there were literally no restaurants that served Korean vegan food. And although my mom was a good sport and tried her best to cook for me without using animal products, she lived 45 minutes away (not to mention the fact that I was a grown ass adult!). I really didn’t want to spend the indefinite future subsisting on salads and French fries, so I had to start cooking.

Plus, I was still inspired to impress my then boyfriend.

Undoubtedly, the dish I was most proud of making back in those early days was vegan chong-gak kimchi, also known as “ponytail kimchi.” It was my favorite kind of kimchi and I was so worried I’d have to give it up when I went vegan (most traditional recipes require fish sauce and shrimp paste). I’ve talked about this before, but it bears repeating that my fear of giving up kimchi was really symbolic of my fear of giving up my Koreanness. Accordingly, discovering that my own kimchi tasted even better than my mom’s was quite thrilling!

But, kimchi is a full day’s production, so it wasn’t something I undertook very often. Doenjang chigae (fermented soybean stew), on the other hand, was on the menu practically every week. It was so easy to make, so hearty and delicious, and best of all, the leftovers often tasted better the next day. It is one of the most popular recipes from my cookbook and I can’t even tell you just how happy I am when I see so many people making a dish that my own mother used to be nervous about sharing with non-Korean people. My husband (the aforementioned boyfriend I tried to impress with my cooking skills) LOVES doenjang chigae, too!

The truth is, Vegan Accountant, I didn’t grow up learning how to cook at my mother’s elbow. I wasn’t eager to throw on the apron when I got a place of my own. And I certainly wasn’t thrilled about having to cook my own food when I went vegan, believe me. But, I was surprised at how much I liked my own food–much better than takeout or even most restaurants. And then, of course, when I started sharing it, I saw how much joy it brought people, it became more than a mere necessity. It became fun, challenging, and even exciting, sometimes.

I’m not exactly passionate about cooking, per se. I’m passionate about feeding people’s souls, and cooking has allowed me to do that in a way that I never imagined.

Hopefully, you’ll find plenty of things in your own kitchen to help feed your soul, too.

Wishing you all the best.

Updates/Random Things.

- What I’m Watching: Anthony is studying to become certified in Italian at the highest possible level and therefore, we thought it would be fun to watch something in Italian. We previously watched and loved The Trial (a legal suspense thriller) and Suburra (a sprawling drama based on a true story about the mafia in Rome). I was in the mood for something a bit lighter, so we settled on The Invisible Thread, a film that centers on a young man with two fathers. It touches upon the unpredictability and resulting cruelty of LGBTQ laws in Italy, while exploring more conventional familial strife like infidelity and basic teenaged angst. Overall, it was very “cute”–it gave me About a Boy vibes, only in Italian.

- What I’m Listening To: In case you missed it, I had the chance to speak with Trace over at Talk with Trace regarding my career, stories, and all things related to TKV. You can check it out here!

- What I’m Cooking: I had my friend Betty over at Stems & Forks hang out with me this past week and we cooked up a storm together, including my seasonal take on the viral butter board that’s sweeping across the internet. In addition, we made up a delicious Genovese pesto pasta dish, some amazing roasted potatoes, along with some really good doenjang chigae. All of these things will, of course, be added to The Korean Vegan Meal Planner!

- The French version of The Korean Vegan Cookbook is now available for preorder and will be in bookstores on October 12th. I’m so excited!!

Parting Thoughts.

When I was 21 years old, I saved a couple grand from my first job out of college and used it to buy my aunt’s beat up old Honda Accord. As my father drove me to pick it up from my aunt’s house, he broke the stillness that typified our car rides by saying, “I’m a little sorry.” I turned from the window to look at him then, his eyes inscrutable as they gazed out onto the street ahead of us.

“Sorry for what?” I asked.

He shrugged his shoulders, something he did when he was embarrassed or uncomfortable.

“I’m your father. I should buy you your first car.”

It was the first time I’d ever heard Daddy discuss what fatherhood meant to him. It was also the first time he confessed feeling inadequate as a dad. My heart splintered for him in this weird, awkward way. Part of me wanted to reach over and put my hand on his shoulder, but I couldn’t. That particular language had never been used between us and I was unwilling to start. Instead, I reassured him, “Oh Daddy, don’t worry! I want to buy my own car with my own money!”

And that was that.

Nearly two decades later, I asked my father if I could interview him for my book. But we were unpracticed at talking and our conversation quickly devolved as it often did. I was determined, though, and told him I would schedule a date during which the three of us–me, him, and Omma (who sometimes acted as a translator for us)–would sit down for a couple hours, while I mined through the stories from his childhood. But, I never got around to it, and assumed he’d soon forget.

One afternoon, sitting on the el, my phone dinged. I looked down to see an email from my father, with an attachment. Must be some letter he received from the bank, I thought to myself. But it wasn’t. It was a Word doc, one entitled, “My dear Jaesun and Joanne.” I opened the document. It started with: “Here is my life story as truthful as I can make it.” The el ride from River North all the way to the South Loop, where I lived back then, is about 19 minutes in total. I was intrigued by my father’s email and figured I could get started on the story of his life while on the train. By the time the el dropped me off at my stop, my eyes were swimming with tears. Father-daughter relationships can be complicated. This can be exacerbated when your father is an immigrant. The language barrier, cultural differences–they can contribute to making it a little difficult to bond in the way that others find to be so easy.

Clearly, he’d not only fully understood my words, “Daddy, I want to hear the story of your life,” they’d taken root and grown into a 6-page single spaced Word document that he typed up all by himself.

I typed out the following email in reply:

“Daddy, this is a treasure.”

I had never written anything to my dad fraught with so much emotion.

I hit send.

Maybe some barriers aren’t meant to be torn down. Rather, they’re made to be hurdled, to ensure you’ll always cherish what lies behind them.

– Joanne