BDD, Fighting the Voice of Imposter Syndrome, and an Act of Power.

Read Ep. 10 | Show Notes

Trigger Warning: This week’s newsletter covers topics that may be challenging for you to read, including eating disorders, body dysmorphic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide.

While I like to think of myself as fairly progressive, to be honest, I’m firmly situated in Gen X and therefore, I’m probably a little “stuck in my ways” when it comes to certain things. It’s one of the reasons I’m so glad to have become more active on social media platforms like TikTok, where young people have taught me a vital lesson:

Age is no excuse for continued ignorance.

The term “continued,” of course, is the key word, since age can and often is an excuse for one’s initial ignorance. It’s really the “head in the sand” obstinance that I’ve been challenged with over the past few years, and while I still harbor a few “curmudgeon-y” opinions that milleneals may find hopelessly antiquated, I like to think of myself as open to being persuaded by all competent appeals to logic and compassion, regardless of age.

One of the things that I used to roll my eyes at was the use (or overuse, in my opinion) of the word “trigger.” I grew up in a home with two grandmothers who would have snorted as derisively as you can imagine at phrases like “depressive episode,” “trigger words,” and “disordered eating.” In fact, “mental health,” in general, was considered simply to be an extrapolation of physical health. Given my family’s history, and Korea’s history, in general, with war and poverty, the prevailing thought on health, including mental health, seems to be “if you’re not starving to death, you’re fine.” Couched in this sentiment is the notion that we should be grateful for food, full stop. Thus, ailments like depression, eating disorders, or body dysmorphia are merely expressions of entitlement, what we elect when we are cocooned in the soft comforts of abundance.

I was a student of this school of thought for the majority of my childhood, and while I can empathize with my grandmothers’ impatience with what they viewed as inexcusable frailty, the irony is that both sides of my family have a history of mental illness. On my father’s side, my aunt has been fighting schizophrenia since her early 20s. Before that, my grandfather (her father) suffered his first nervous breakdown before he was 13 years old, after watching his mother commit suicide. On my mother’s side, I remember hearing stories of my favorite aunt trying to rip her own tooth out with a wrench, which is why her smile was always crooked.

My own tough-as-knotted-tree-roots Seoul Hahlmuhnee (maternal grandmother) was plagued with horrifying night terrors for as long as I could remember, right up until she passed away. I used to hate having to share a room with her. At night, all the most frightening moments of her life would revive themselves like ghosts and she would be forced, once more, to fight them off with her bare hands. I was too young to know what “PTSD” was while I cowered beneath the comforter, trying to drown out the voice splintering the fuzzy night air in our Wilmette house, to unsee my grandmother’s walnut face contort in a kind of fear I hoped never to reckon with.

Age was, in that case, the excusable culprit to ignorance; however, since then, I’ve not only filled in some of the blind spots with respect to my grandmother’s story, but I’ve also become acquainted with the effects of post-traumatic stress disorder, particularly how PTSD manifests in participants and/or victims of war. The concept of “trigger” in PTSD is critical. According to Lori S. Katz, PhD, a clinical psychologist working with victims of sexual trauma: A trigger is when something in the current environment, perceived either consciously or unconsciously, activates a neural network of danger. This initiates a neurochemical chain reaction to help the person protect oneself from danger (e.g., the fight, flight, or freeze response). The person may become hyper-alert to perceptions of danger. This would be an efficient neural network, ready to detect and protect. While this would be adaptive if there was indeed a danger, it becomes very upsetting when there is no imminent danger.

In some ways, this explanation of trauma and “trigger” reinforced my skepticism and, I’ll be honest, contempt for the frequent and cavalier use of words like depression. Indeed, despite my own personal encounters with self-harm and years of therapy, I was still largely unconvinced that depression was a real thing. I believed it was a made-up disorder designed to do the thing I hate the most: play the victim.

It wasn’t until one quiet afternoon, a few months before my wedding day to Anthony, that I realized just how dangerous my dismissiveness could become. It should come as no surprise that the minute I started wedding dress shopping, I grew acutely aware of my size. It didn’t help that the woman fitting me on my first day said “you have a little too much back fat…” as she tried to zip me up into the dress I ultimately selected. That comment settled into brain, made itself a nice and comfy home there, “rent free” (as the kids like to say). It was time to “diet again,” I told myself, to make sure that all the excessive back fat disappeared in time for the wedding.

A few weeks in, I decided to try on some of the dresses I kept in my closet not to actually wear, but to serve as a handy dandy substitute for a scale. There was one dress in particular–a cream suit dress with navy blue trim from H&M. To this day, I’ve never worn this dress outside of my home, but I’ve spent hours hunched over my bed, my arms at odd angles, sweat trickling down my face and back, as I forced the zipper up and up and up until it finally reached its zenith.

Except on that day… it didn’t.

I collapsed into bed, the dress halfway around my waist. The sun was streaming in through our bedroom windows, my dog dozing in the living room. Anthony was thankfully at work, so I could sob miserably into our comforter, “I’m fat! I’m fat! I’m so FAT!” Even as I write these words, I’m at once ashamed and scared–ashamed of how mean I was to myself and scared at the mere memory of what I felt that afternoon. Because for the first time in awhile, as an endless road lined with calorie calculators, “goal jeans,” cardio sessions, and the dull ache of hunger unfurled out in front of me like the long grey tongue of an angry whale, I wanted to end my life.

Another term I’ve become acquainted with these days is “snowflake,” referring to those who are unequipped with adequate mental toughness to deal with everyday life, and therefore melt at the first sign of heat. There are many who might hear my recitation of this meltdown in my cream colored dress and call me “snowflake.” In fact, I might have been one of them a few years ago. But, normative barometers of toughness are far less relevant or useful than measurements of the actual pain. Against the one fundamental moral law–does it cause life? or does it cause death?–it doesn’t really matter if someone else’s suffering would bring you to your knees; it only matters whether it cripples them.

Sure, toughness is something we should all aim to cultivate, in order to guard against falling apart over spilled milk because this is not a generally pleasurable way to live. But, judging someone in crisis–however ridiculous you may deem the circumstances–is not terribly effective in the moment, and, more importantly, is often based upon a lack of information. We have almost no way of knowing the universe of lived experiences that makes someone particularly susceptible to certain ailments, just like I had no way of knowing why my grandmother started screaming in the middle of the night.

“Triggers,” when repeated and relentless without giving the brain adequate time to recover and repair from the inflicted wound, can cause serious psychic damages. Put more scientifically, triggers cause the release of cortisol, the body’s evolved reaction to the “flight or fight” sensation. Excessive doses of cortisol can lead to a host of medical and psychiatric problems, including Cushing’s syndrome and depression.

I have spent the past couple years studying philosophy (here and there), reading up on ethics in order to inform my evolving values as it pertains to the role of compassion in our daily lives (e.g., my veganism), and I’ve concluded that there’s really only one moral law, from which all other moral laws spring:

“Life is good. Death is bad.”

I guess more accurately, causing death is bad. Those things that affirm life, on the other hand, are inherently good. As I lay there, half naked, weeping into our bed, I felt so hopeless. I would have to spend the rest of my life guarding against the “dangers” of “being fat,” and that life wasn’t one I wanted to live. The sick part of it all, of course, was believing I had no choice in the matter, and that therefore, my only escape was of the permanent variety.

“Rock bottom” has the tendency to jolt you out of the status quo, though. Intellectually, and perhaps primally, I knew that I was tiptoeing around a chasm, one that would suck me in as indifferently as a black hole.

And I rejected it.

I loved life. I was about to marry the man of my dreams. We had a beautiful home together–one filled with sunlight, comforters, and puppies. I didn’t want to give those things up and it terrified me that I could even consider doing so, simply because I didn’t fit into a dress. Because a woman had carelessly made a comment on my “back fat.”

I wish I could say that after that moment, of hitting that rock bottom, I no longer struggled with my body. But our stories, however much we want them to, don’t always line up with Hollywood narratives or self-help blogs. The truth is, I knew how dangerous my self-talk could be, and though I loosened the reins on my diet, I was still very self-conscious and apprehensive, especially as our wedding day drew near.

I didn’t know it at the time, but I had body dysmorphic disorder, a mental health disorder characterized by excessive preoccupation with the way your body looks, to the point that it interferes with daily and normal functioning. Those who suffer from “BDD” may take extreme measures to “correct” the perceived flaws in their appearance, like repeated crash dieting and surgeries (guilty as charged…). But, of course, nothing you do will ever be enough, because the real problem isn’t in your physical appearance. It’s in your brain. Indeed, restrictive eating habits can often exacerbate the symptoms of BDD, as the body’s hormones react to the lack of calories. Left untreated, “BDD can lead to severe depression and suicidal thoughts and should not be ignored.”

Eating disorders and BDD, like most mental illnesses, can be dangerously isolating, and it’s thus easy to trick ourselves into thinking that our symptoms and struggles occur inside a vacuum, that the bystanders to our pain are not affected, or not affected enough to make any difference. I liked to believe that because I permitted my little “closet outbursts” to occur when Anthony was out on a run or at work, I’d done a good job of keeping my embarrassing deficiency (and that is truly how I viewed it–a deficiency) largely private, and that I could continue to keep it that way for the duration of our marriage. I soon discovered that however much I tried to hide my truths–even from myself–they have a way of crawling out and declaring themselves in the most inconvenient way.

My BDD decided to declare itself to Anthony at the most inconvenient time EVER.

On our honeymoon.

Hindsight is 20/20, right? I should have known that this was all going to lead to some spectacular conflagration with the person who was, by definition, the most intimate with me and my body. It was triggered by something as seemingly innocuous as the comment at my first dress fitting. It was the last full day of our honeymoon. We were enjoying it on the rooftop of our hotel in Rome overlooking the dome of the Pantheon. Aperol spritzers were all the rage that summer, and after a long day of thrift-store shopping along the cobbled streets of Trastevere, I decided to treat myself to the fizzy orange cocktail that I’d avoided up till then.

I was wearing a vintage cotton Nike t-shirt I’d picked up earlier that day, with a flowing white skirt that was quite popular in Europe, one that cinched around the waist and was designed to cascade down the rest of your body like a waterfall. I’d been dieting right up until the wedding night and therefore, had let myself indulge in whatever I wanted to eat (vegan, of course) throughout our days in Sardegna, Turin, and Rome (the three legs of our honeymoon). Although the skirt didn’t cinch quite as much as I wanted to, I reasoned, “You’ve been dieting for half a year in preparation for the wedding. You’ve earned this Aperol spritzer.” Anthony thought I looked picturesque on that rooftop in Rome, probably because I did–I was happy, content, and in love in quite possibly the most romantic place on the planet. So, he did what any other newlywed husband would do: he whipped out his phone and took a picture of his bride.

And then, he made the mistake of showing me the picture.

I take that back. That wasn’t a mistake. The mistake was mine, of course. In agreeing to look at it.

The fact that Anthony was proud enough of that phone-pic to show it to me proves that he believed I looked lovely. But, I thought the opposite. In fact, I was devastated by my appearance. Once again, I thought I looked too large. Despite all the beautiful photos our wedding photographer had already shared with us, I was convinced that those were a lie and that Anthony’s one phone pic taken at an odd angle with the light slanting across my body in a very weird way was THE truth.

I smiled at the photo, notwithstanding my disgust. I didn’t want to ruin an otherwise perfect afternoon. But the image burned itself into my brain and began to mete out its poison at almost imperceptible doses throughout the evening. The following morning, the last morning of our honeymoon, as soon as I opened my eyes all I could see was that photo. And all I could think was this:

“How could my husband possibly stay in love with someone as hideous as me?”

I was absolutely certain that it was only a matter of time before either (a) Anthony would divorce me for being unattractive or (b) our marriage would devolve into one of those passionless, asexual relationships that resembled two roommates more than two lovers. Knowing that I was destined for Anthony’s rejection of me and my body, I did the only logical thing: I rejected him first.

I pulled away from him when he tried to touch me. I turned my back to him when he drew near. I stopped talking to him and instead, stared off into the corners of our honeymoon suite, pretending to count the number of different cornices that decorated the lavish ceiling. What I wanted, of course, was him to pull me into his arms despite my coldness, and reassure me that he would always love me, he would never leave me, that he found me as desirable as the day he stumbled upon my OkCupid profile, if not more. In my messed up brain, my overt aloofness was all the invitation he needed, but of course, Anthony saw things a bit differently. He eventually rolled out of bed and started packing for the airport, which, of course, confirmed to me my very worst fears: that he found me so repulsive, he couldn’t wait to get out of our bed.

I spent the rest of our last honeymoon day treating my husband as if he were stranger, swinging between genuine hurt and seething resentment–both of which were self-inflicted, even if I lacked the awareness to realize it. By the time we got to the airport, we were hardly talking to each other. In a fit of temper, I finally broke the silence to confront him in the sitting area of our gate at FCO. I taunted him with, “So this is how you’re going to be on the last day of our honeymoon?” as if the unbearable frigidity between us was somehow his fault.

You’re probably saying to yourselves, “Man, Anthony shoulda filed for divorce right then and there in the freakin’ airport!” LOL. A part of me doesn’t blame you. I like to think of myself as a mature, generous person, one who possesses sufficient self-awareness to guard against inexcusable bouts of selfishness and narcissism. But, there is no doubt that I was being inexcusably selfish that day. I ruined not just my own day, but my husband’s, a man I’d vowed to love before all our guests on the rooftop of our hotel, a million unblinking stars witnesses to my oath. But my brain was not working properly. At some point, it had taken a sharp left turn and I found myself somewhere outside of reality, but inside my own created reality, one where danger lurked at every turn.

You’ll be happy to know that despite my behavior that day, Anthony did not leave me. If anything, the severity of my delusions, that I would allow them to ruin my freaking honeymoon, prompted me to have more honest conversations about my disorder with Anthony. Specifically, Anthony is now far better versed with my “triggers” and is more careful about taking and sharing photos of me, going on “water fasts” without advance notice, or saying things like, “Wow, you ate a lot today!” It is a work in progress, but every day, I grow more acquainted and comfortable with an idea once peddled to me by my therapist: “Anthony loves you for your brain, not your boobs.” Due to his patience and willingness to help me carry some of the baggage that saddled me when we fell in love, we were both granted a breathing spell from some of the most jagged edges of my disorder. During that respite, I started to think more about how my view of myself impacted him.

I remember feeling on that last day of our honeymoon not just embarrassment for myself. Implicit in my self loathing was also a profound disrespect for the man who could be attached to someone as unworthy as me, and, as a result, I was also embarrassed for him. As I projected my worst fears onto him, my own feelings were all-consuming and his were silenced. He was no longer allowed to be Anthony; rather, he was some caricature of that man, the one I’d created in my head. Despite committing myself to a partnership, I unilaterally decreed that Anthony’s view of me was illegitimate and that my own view of me would be codified and built into the backbone of our marriage, even if it meant the destruction of that marriage.

There are all sorts of reasons I developed an eating disorder and BDD, many of which were out of my control. Korean culture can be harsh with girls and their valuation, and I was made to feel “too big” from as early as I can remember. While knowing this can inform my treatment, at the end of the day, it doesn’t change the fact that our choices–even really really hard choices, especially really really hard choices–define who we are and that love, fundamentally, is a choice. Perhaps the most important choice you’ll ever make. In choosing to be unloving to myself, I had also, unwittingly, chosen to be unloving to my husband. This was an unacceptable breach of the promise I made when we got married.

Thus, even though I’d admittedly tripped up and fallen, I got back up, dusted myself off, took Anthony’s calloused hand in my own, and put one foot in front of the other with just a tiny bit more confidence as I advanced along the path my therapist set out for me on the very first day I walked into her office:

“Loving yourself will be the hardest thing you ever do.”

At the end of the day, BDD is, in some ways, a manifestation of imposter syndrome. I am at all times anxious that the me I see in the mirror will eventually be revealed. The danger in imposter syndrome is that it allows this alternative reality to prevent us from self-actualization. We act as if we are imposters, until we eventually become the imposters we fear. In some ways, the inevitable coalescing between our internal world and the external world can even be reassuring. Confirmation bias can quiet the anxiety caused by the constant (if manufactured) need to pretend, even if the bias is negative and harmful. So, we go out of our ways to prove that yes, our version of reality is reality–we are ugly, we are incompetent, we are losers, we are unloveable, we are unworthy. It sucks, but at least it’s consistent with our view of the world and we no longer need to spend so much energy hiding these truths.

But what if…what if these are the biggest lies in the universe?

Imagine if someone told your daughter, your son, your best friend, your sister, your father: “You’re ugly,” “You’re too fat,” “You’re good for nothing,” “You’re a lousy human being,” “You’re unworthy of love.”

Would you stand for it? Would you say, “Yup, that’s the truth, and thank God it’s been revealed!”

NO.

You would call it out for the lie it is so why, why on earth, wouldn’t you do this for the person standing in front of the mirror?

Try replacing the defeating self-talk with the following:

- “Yes, you totally effed up at that thing at work, but at least you’re the type of person who’ll take responsibility for your mistakes and be part of the solution.”

- “Sure, it would be great if I could fit into this dress, but all those people who love me don’t condition their affections on whether I can fit into this dress and if they do, they aren’t worthy of my love.”

- “You may not look the way you want, but the things you do make you an incredibly beautiful person.”

- “Yes, you’ve made a bunch of mistakes in life, but at the end of the day, you always try to do the right thing.”

- “You’re not perfect, but you’re absolutely worthy of your partner’s respect, love, and even forgiveness.”

And if, at any point, you start to worry that saying these nice things to yourself is somehow a sign that you lack mental toughness, remember this:

Loving yourself is the hardest thing you’ll ever do.

Ask Joanne.

Hi Joanne, I am really struggling with uncertainty. I know it sounds like something I should be used to after 2 years of a pandemic but I honestly think all this time of dealing with the unknown and trying to navigate being an adult for the first time is really wearing me down. I have a meltdown every time something doesn’t go my way and my anxiety is at an all-time high right now. I really want to be more resilient but I have no idea where to start. -Jazz

Jazz, hopefully, it will comfort you to know that a lot of people likely feel the same way, even if they aren’t brave enough to admit it like you are. Trying to get used to severe uncertainty is like trying to get used to walking on a tightrope. It’s not possible because you can’t take your balance for granted. Every single step is fraught with tension, stress, and danger, particularly if there’s no safety net beneath. Regardless of the cause of this level of uncertainty (a global pandemic is certainly a legitimate one), don’t chide yourself for not being used to it after 2 years. Instead, let’s turn our attention to creating that safety net, or, better yet, removing ourselves from the tightrope altogether and replacing it with solid ground.

Speaking of solid ground, when was the last time you went on a walk without a destination in mind? Did you know where you’d end up? Who you might encounter along the way? Whether it might rain at some point? If the answer to any of these questions was “no,” did that prevent you from going on that walk? In many cases, my guess is you probably still headed out the door, perhaps with an umbrella and with your phone, just in case. You see, there are all sorts of unknowns that you don’t really think about when you go for a walk or, if you do, that don’t stop you in your tracks. Why? Because even if you’re unsure of where you’re headed, you know how to get back home. Even if you don’t know who you might meet along the way, you’re reasonably certain that none of them will cause you unwarranted harm or, even if they did, you could protect yourself. Even if it starts to rain, you’ve brought an umbrella and if you haven’t, well, it ain’t gonna kill ya to get a little damp.

Life is a lot like that walk–full of uncertainties. And sure, when you become an “adult” (however that’s defined) and you no longer have a guardian (i.e., a parent) to go out on that walk with you, a lot of those uncertainties can appear to be more dangerous. It’s all too easy to start laser beam focusing on these “unknowns” over which we have no control and forget about the things we do control, until we are literally paralyzed and can no longer walk at all. But what if we switched things around and focused on the things we do know? Like:

- Even if I make the wrong judgment call at a critical juncture in my future, I’m still a good person, one who is guided by my values. Whatever I end up doing with my life, I know I will always try to live it with integrity.

- Even if I fail, make a total embarrassment of myself in front of my family and friends and colleagues, I know I’m strong and will eventually recover. I’m also smart and good at learning from my mistakes.

- Even if I have a meltdown in a very public and not attractive way, I know my loved ones will understand that I’m working through my anxiety and that however alone I sometimes feel, I’m never truly alone.

- Even if my heart is breaking right now because someone I love doesn’t love me back or in the way that I want, I know that this doesn’t mean there’s something inherently wrong and unloveable about me. It just means we aren’t right for each other.

I’m a big believer in writing things down. It’s one of the things that helped me when I was struggling with chronic anxiety during law school and it remains my “go-to” when stress starts to spiral out of control. The next time you feel overwhelmed with uncertainty, try writing down all the things that are eating away at you. Use bullets instead of full sentences if that makes it easier (that’s what I do). It might look a little like this:

- Job application

- Tomorrow’s interview

- COVID

- Car insurance money?

- Why s/he isn’t calling me back

- Am I texting too much?

- Job application [again]

Afterwards, go back and write something next to each bullet that you do know:

- Job application / I’ve got 5 other job applications out there and I won’t stop trying until I get a job, even if it takes me longer than I expected.

- Tomorrow’s interview / I’ve got my outfit all picked out and I’ve spent the past hour researching the company so I NAIL this thing.

- COVID / I’ve done everything I can to mitigate the risk of getting sick and that’s the best I can do.

- Car insurance money? / Worse comes to worst, I know mom will lend me the money, even if she makes me eat a LOT of humble pie.

- Why s/he isn’t calling me back / I know they’re busy at work, but if it’s because they don’t want to talk to me…why do I want to talk to them?

- Am I texting too much? / Maybe. But only if they don’t want to talk to me and if so, again, why do I want to talk to them?

- Job application [again] / Same as above.

The above exercise has helped me immensely, not just to organize my anxieties but to instill some confidence in myself.

Finally, one more thing: as a lawyer, I often felt such overwhelming stress, I wanted to throw my computer out the window or just walk out the doors of my office and never turn back. Sometimes, the most stressful thing about work was not knowing what the day would bring. Would the judge side with me or my opposing counsel? Would my client be happy with my draft brief or would they want to fire me? Would I get a good review from my practice group lead or would they tell me I needed to work harder, do better? But you know what made my job bearable, even on the most stressful days? My work BFF–the guy I could count on to go with me to Starbucks every afternoon at around 2:45 pm, the one who always sat next to me at the office luncheon because he knew I was still too shy to socialize with my colleagues, the one who let me sit in his office and cry when one of the partners I worked with was out of line, the one who swung by office every morning before the work day got under way so we could gossip, nerd out over running, or just vent.

You see, Jazz, one of the most joyous things that can happen on your walk is the unexpected encounter with someone you eventually want to walk with. And I’m not just talking about your future spouse or partner. It could be a friend, a pet, a colleague, a mentor. My point is, even as adulthood looms in front of you, you don’t actually need to do this alone.

Wishing you all the best.

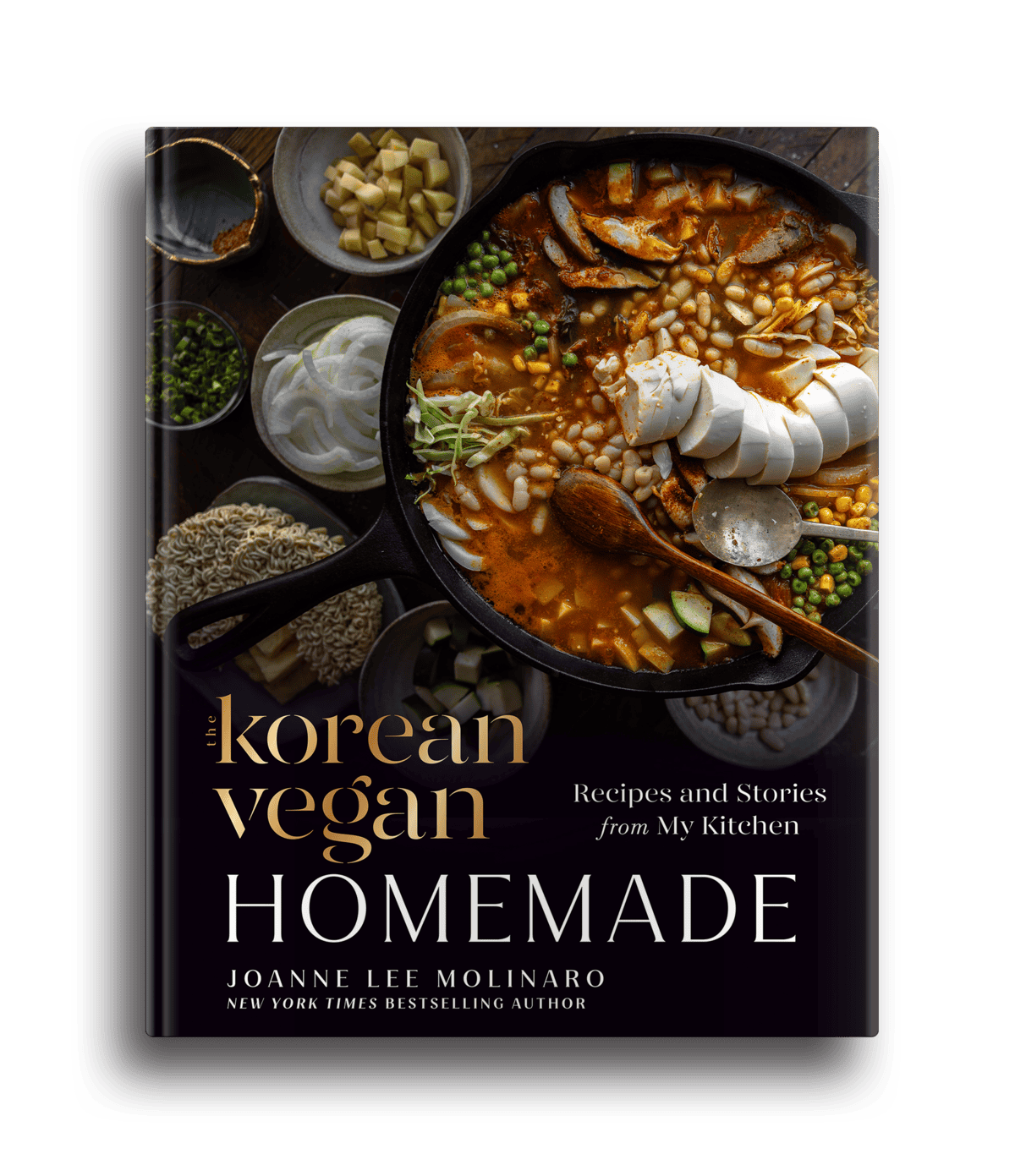

TKV Meal Planner Recipes, Next LIVE Cooking Demo, and Updates.

This week, I added four new recipes to the TKV Meal Planner:

- Bibim Breakfast Tacos

- My Favorite Instant Ramen Noodles

- Simple Spicy Doenjang Stew

- Banana Chocolate Chunk Bread (not pictured)

Also, a friendly reminder that the next live cooking demonstration for TKV Meal Planners will be on June 29, 2022 (keep an eye out for an email with the details). We’ll be making Tofu Fried Rice! Not a TKV Meal Planner yet? For less than $2 per week, you not only get this LIVE cooking demonstration, you’ll get instant access to all the recipes, food coaches, and more!

Announcements.

- TORONTO!!! Yes, I’m FINALLY headed across the border!! I’m working with an incredible non-profit organization, Han Voice, to celebrate a pop-up art exhibit, People’s Museum of North Korea. The event will be on July 2 and you can buy your tickets here. See you there!

- After posting one of my videos this week, I received about two dozen messages and comments requesting that I identify the tripod I used. Unfortunately, that tripod is no longer available. However, I’ve found one possible alternative and created an entire Amazon Storefront of all my favorite products. So, for all of you who want to know everything I use to make my videos and recipes, check it out!

Parting Thoughts.

I recently posted a short video about my dad for Father’s Day. In it, I talk about how, within the first week of moving into our new home here in California, our dog Rudy, who has been losing his vision, slipped and fell into our swimming pool. Luckily, we fished him out within seconds, but by that time, he’d already swallowed a great deal of water into his lungs. He had to be placed in an oxygen incubator in the ICU for two days. Needless to say, those two days were agonizing. I was not only terrified of losing my Rudy, especially after how hard he worked to get to California in the first place, but I felt totally responsible for his suffering. Despite wanting to spend the hours staring listlessly out at the hills surrounding our new home until I could again hold Rudy in my arms, my parents were with us. Therefore, I tried my best to pretend I was “fine” for their sake: I didn’t want them to worry about me on top of worrying about Rudy (over whom they doted like grandparents). I thus threw myself into making our new house a home—unpacking boxes, setting up the Wi-Fi, assembling patio furniture.

I had purchased one of those swinging “egg” chairs from Wayfair and decided I would try putting it together by myself, despite the repeated warnings on the instructions that it was best to have at least 2 (if not 3) people assemble it. It was getting late—twilight settled in around us like an old friend who knew better than to announce his arrival. My entire family was drained from spending hours at the animal hospital or worrying about Rudy, and I didn’t want to bother them, so I dragged the huge box outside and set up shop on the far end of the pool. But within a few minutes, my father joined me. As I lay all the parts on the ground, he studied the instructions for a bit before picking up a screwdriver. “Daddy, you don’t need to help. I can do this myself,” I said, but he ignored me. Didn’t say anything. Just starting pulling together the pieces for Step 1. We spent the next 45 minutes making my swinging egg chair. He held the heavy pieces upright so I could screw them together, helped me fasten the nuts, and then, of course, tightened each and every bolt I screwed into place, a reminder that yes, my 78-year-old father’s hands were still stronger than mine.

We didn’t say much to each other—“hand me the screwdriver,” “Ok, Step 3,” “It’s heavy, be careful.” In the end, though, we had a perfectly erected swinging egg chair, swaying lazily to the soft So-Cal breeze. Daddy walked back into the kitchen without even sitting in it. I nestled into my chair as if in a cocoon, letting my toe push off the floor every now and again, wondering whether the coil in my heart would eventually spring, whether Daddy’s act of wordless love had helped to loosen it or kept it held together a little longer.

Power is defined as the “ability to direct or influence the behavior of others or the course of events.” But power is not reserved exclusively for the rich and famous, for Jeff Bezos and the Elon Musks of the world. You don’t have to be the CEO of a Fortune 500 company or an Armani wearing executive of a coveted C-Suite to have power. You don’t have to have 30 million followers or be the star of a YouTube channel to have power. You don’t have to rake in a 7-figure income, live in an estate in the Hamptons, and ride a private jet to have power. In fact, a lot of those things are often poor substitutes, even compensation for the lack of power. When I think about my father, who worked the night shift at the USPS his whole career, his small, humble acts of service to me while I was suffering, how he helped me put my swinging chair together when I was so close to falling apart, I ask myself again and again:

What is love?

Love is a choice.

Love is an act of power.

What will you choose to do with your super power this week?

– Joanne