Am I Still Proud to be American?

I dunno about you, but Independence Day always meant a long weekend, BBQ, fireworks at the beach, and a mandatory rewatching of Will Smith killing a bunch of no good aliens while Bill Pullman reaffirmed that this–i.e., destroying a bunch of aliens that were trying to take over the world–was the real reason I was so proud to be American.

I’m kidding.

Sort of.

In truth, just a handful of years ago, I would have described myself a patriot, someone who proudly stood for the flag, though staunchly defended the First Amendment right to kneel before it. I loved U.S. History in high school and fully bought into the idea that our Founding Fathers were brave, brilliant men who unshackled themselves from oppression through sheer will and brute intelligence. I loved law school, particularly the classes dealing with Constitutional Law–my favorite professor kept a miniature copy of the Constitution in his breast pocket at all times, and he’d whip it out every now and then and read out loud from it as if he were telling a bedtime story.

I remember I took one Comparative Law class in which the young, visiting professor from Germany went on for 20 minutes about how the US Constitution was the only formational document of its kind in the world, in that it remained virtually unchanged (relative to the charters of other sovereign states) since its origination. At the time, I remember nodding my head enthusiastically, thinking to myself, “Yep, that’s because our Constitution is better than everyone else’s,” not realizing that my professor probably meant this as a criticism–not praise.

Yes, I fully subscribed to the notion that America was the greatest country on the planet, built upon the exigencies of liberty and the transcendental notion that joy could be inherited by anyone with a little gumption and a willingness to dream. In retrospect, my rosy-colored view of my country was, in large part, a product of the things we learned in school (“Give me liberty or give me death” just sounded so cool!), as well as my father’s passion for American politics.

I think that’s what it really boiled down to–I learned just by watching my Dad that you could be really upset with your country, while still loving it enough to care. It reminds me of one of my favorite passages in The Scarlet Letter by the great American author Nathanial Hawthorne:

It is a curious subject of observation and inquiry, whether hatred and love be not the same thing at bottom. Each, in its utmost development, supposes a high degree of intimacy and heart-knowledge; each renders one individual dependent for the food of his affections and spiritual life upon another; each leaves the passionate lover, or the no less passionate hater, forlorn and desolate by the withdrawal of his object.

Love of country can coexist with hate of country, but the real dagger to patriotism is indifference.

Probably because we’ve spent the last 19 days traveling across Europe and we’re currently obsessed with The Americans, I’ve been thinking a lot about whether or not I’m still proud to be American. I was actually sitting at a cafe in Terminal 3 of London’s Heathrow Airport listening to the clipped chatter of Brits all around me and I thought to myself, “I wonder if Britons are still proud of being Britons?” Given everything I’ve read about the UK over the past few years–the disgraceful resignation of its Prime Minister, the prevailing scandals that blanket the royal family, and the country’s not yet fully consummated breakup with the EU–it was a fair question. My agent, Charlie, who is so British I can’t understand about 20% of his English, often includes at least a sentence or two in his emails lamenting the state of affairs in England, as if to commiserate, “You Americans aren’t the only ones who have it bad…”

Do we have it bad? I didn’t think so. Not for a very a long time. Sure, I’ve always known racism existed here in the United States. The kids on the playground who slanted their eyes at me while chanting “Chinese, Japanese, dirty knees…” did a pretty spectacular job of demonstrating racial ignorance at the tender age of 9, if only because I am neither Chinese nor Japanese. The unabashed Islamophobia that gripped the nation after 9/11 infuriated me, enraged me, but only because I knew we could be–should be–better than that.

And then… 2016 happened. It seemed that at least half the country I loved so much maybe didn’t love me back. At least not enough to defend me and my family from what seemed to be obvious–a president who didn’t really care for immigrants. Anthony once asked me why I was so against Donald Trump becoming president and for a second, I was at a loss for words that I actually needed to answer that question before blurting out: “Because he stands for everything that is against me and my family.” Perhaps because I’d been subjected to “Chinese, Japanese, dirty knees” or some variation thereof my entire life here in the United States, I was particularly attuned to the rhetoric of racism, and as such, I could see that writing on the wall long before that nightmare became a reality.

I was absolutely devastated when I discovered that so few could see that writing with me.

It was the first time in my life I started to question whether America was as beautiful as I always believed it to be. Because it was the first time in my life I didn’t feel particularly safe in the country I called home. It was the first time in my life I began to see just how many people didn’t view me as “American enough,” simply because of the color of my skin, the kind of food I liked to eat, or the fact that I sometimes spoke in Korean when I was with my family.

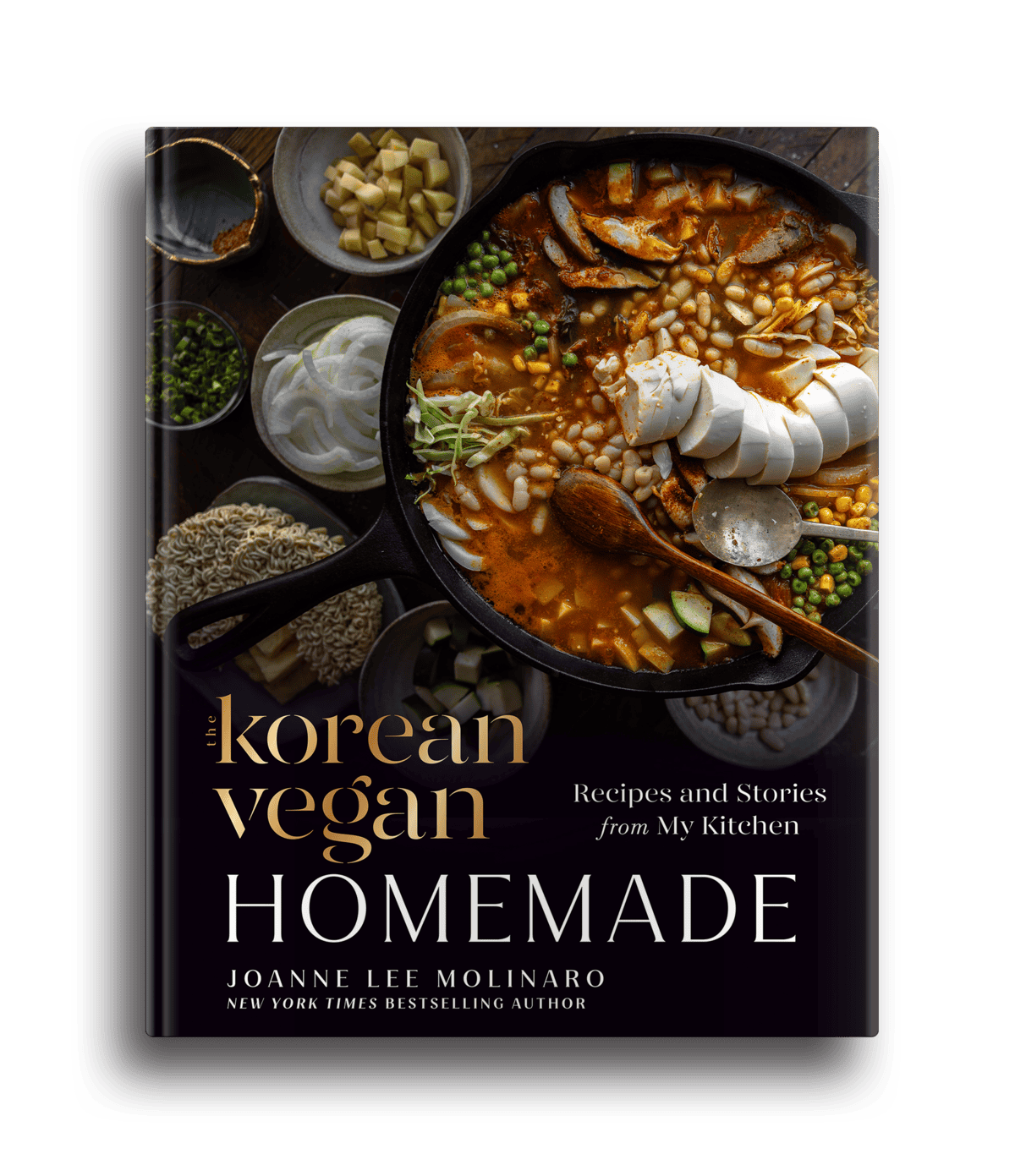

As you all probably already know–this hurt is what led to The Korean Vegan, as you currently know it. I felt profoundly betrayed by my fellow Americans, but my 7th grade math teacher didn’t call me a “problem solver” for nothin’. I didn’t see how the problem of America could be solved by spilling my rage onto the cacophony that was Facebook or picking a fight with my Trump supporting relatives (yes, I have quite a few). Rather, I chose to continue believing in the people of this country, assuming that it was simply a lack of information that led to their tragic selection for the Oval Office.

Thus, instead of contributing my voice to the collective rage, I decided to fill the informational void with stories, hoping that if more people understood what my family was like, they’d be more inclined to reject the politics of hate. I’d learned a lot from my first marriage, how to “fight fair” or to avoid fighting altogether, and I viewed the 2016 election as the first of many alarm bells–one that signaled the potential for divorce. I therefore also committed to listening as much as I spoke, taking ownership of whatever part I played in making so many fellow Americans feel left behind.

It has been an interesting learning experience. For the most part, storytelling has been a creative and personally fulfilling kind of political activism, but I wonder whether it is as effective as simply picking up the phone and begging people to just vote. I realize these aren’t, by any means, mutually exclusive (I’ve participated in more than one of these phone-a-thons), but I do want to be somewhat strategic about how I allocate my own human resources. Moreover, even though I agree that “the arc of the moral universe is [indeed] long,” I often question how we can be so sure “it bends towards justice”?

Currently, things don’t look too good for America:

- We have more homeless people (per 10,000) than Canada, Japan, or South Korea. In fact, we rank smack in the middle when it comes to homelessness, which is pretty depressing given that we are literally the wealthiest nation in the world.

- Despite outspending every other sovereign state on the planet when it comes to healthcare, the US’s life expectancy has seen unprecedented lows while other nations have largely recovered from pandemic related deaths.

- We have more guns than any other country. In fact, for every 100 Americans, there are 120 guns floating around our great nation. Yup–there are more guns than people in America (thanks, in large part, to the immutability of that Constitution I was so enamored with).

- Not surprisingly, we rank #2 in number of gun deaths in the world, #2 in number of gun related suicides, and #1 in school shootings. That last statistic is particularly appalling–Americans sustained 288 school shootings from 2009 through 2018. In second place is Mexico. How many school shootings did they have during the same period? 8.

- As of 2018, we ranked a dismal 22nd when it came to competency in science, math, and reading. Our students scored only slightly above average, while students in China, Canada, France, and Germany (to name just a few) easily trounced us when it came to critical thinking.

- There are more than 100 white nationalist and 99 neo-Nazi groups in the United States, which means there are more neo-Nazis in our country than in the one that birthed Nazi-ism. But what is jaw-droppingly disturbing is that one poll estimates a whopping 22 million Americans are sympathetic to neo-Nazi / white-supremacist ideology.

And yet…

- Approximately 810,000 immigrants apply for permanent residency in the United States each year.

- In 2022, nearly 1 million individuals became naturalized citizens of the United States.

- More than 431,000 individuals sought asylum status in the United States in 2022. The US is the #1 destination for those seeing refugee from their native countries.

While I was sitting in the back of a taxi taking me to my hotel in France just a couple weeks ago, I received a voicemail from my client Mariam. I’ve written about Mariam before. I shared her story in connection with raising money for the New York Legal Aid Group–an organization that, among other things, provides free legal services to those seeking asylum here in the United States. I know some of you will remember Mariam and her story because many of you donated so generously to NYLAG.

For those of you who don’t remember, the following is an abbreviated summary of the work I did with Mariam back in 2020:

Mariam was born in Mali, one of the few places left on earth that still practices FGM, among a number of other unconscionable traditions designed to brutalize women. After undergoing FGM at the unthinkable age of 8, Mariam won a scholarship to study here in the United States, starting in middle school. She studied here all the way through graduate school where she obtained her master’s degree on an F-1 student visa. During grad school, Mariam fell in love and got married here in the States. She was soon blessed with a daughter of her own, and although her family back home was thrilled, they also insisted Mariam bring the baby home so that she could be “fixed.”

That was the terrifying part of Mariam’s situation. Her husband did not have status here in the United States. As such, once she completed her master’s program, her visa would expire and she would be required to return to Mali, where her daughter would almost certainly be subjected to the same horrors that Mariam had to undergo when she was just a child. Indeed, mutilation wasn’t the only thing that would be in store for Mariam and her daughter should they return to Mali. Mariam explained to me that she once left the house to run an errand without first asking permission from her uncle (her male custodian after both her parents passed away), and was beaten when she returned home as punishment. Mariam (and her daughter) would not be able to own any property, get a job, or even have credit cards without permission from a male custodian. In other words, Mariam would have no physical, financial, or social autonomy from a man for the rest of her life.

I met with Mariam the night before her interview with the asylum officer at Homeland Security. I sat across from her in the dining area inside her hotel, copies of her asylum application strewn between us while an LCD TV reported on something called “corona-virus.” I went through a list of questions I’d prepared in advance, warned Mariam that however sure she felt today, tomorrow, she would feel as unsteady as the table we were sitting at, and asked her if she had any questions before we concluded our prep session. And at that point, she reached over and gripped my hand. I can still feel just how impossibly soft her skin felt. She said,

“Joanne. You don’t know. You don’t know how lucky you are. To be here.”

I thought about that for a few seconds, before smiling politely and giving her hand a gentle squeeze.

“I know.”

As some of you may remember, Mariam’s asylum application was approved. Afterwards, I worked with her to prepare her green card application and just a couple days ago, she left the following message on my voicemail:

Hi Joanne. This is [Mariam]. I just wanted to tell you that I got my green card. Thank you thank you so much.... I can never forget what you guys did for me. Thank you Joanne.... Now I can raise my two daughters here in America. Thank you, thank you, thank you so much...

I share Mariam’s story not as an “apology” for all the terrible things I just rattled off about the United States. The US cannot rest on its laurels simply because it has a better human rights record than Mali. Backwards is backwards however far ahead you are in the race. Rather, I offer Mariam’s story as another data point, one that merits consideration when evaluating America’s growth and trajectory–whether it remains on track towards justice, as Reverend King believed.

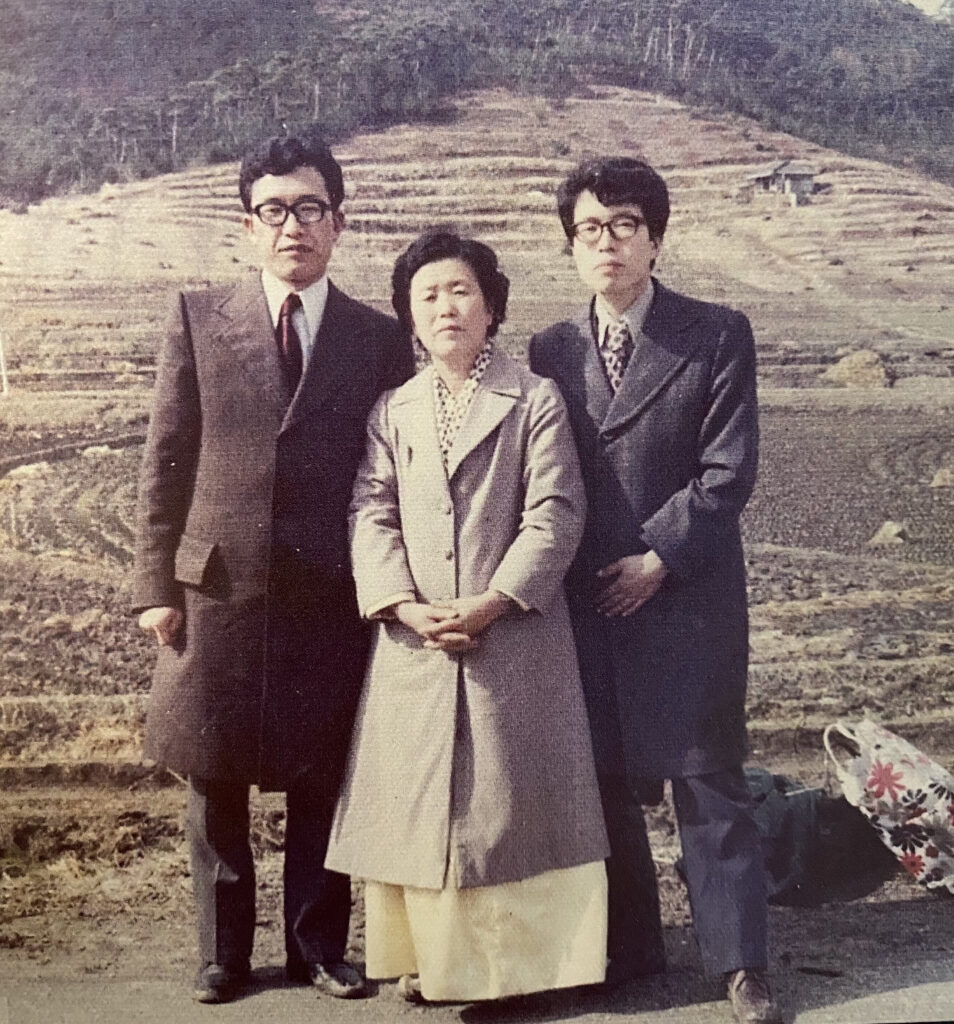

As I mentioned earlier, I believe I inherited an inclination towards politics from my father, who, as you all likely have heard, was born in what is now known as North Korea–something I never really knew until college. Just a few years ago, my husband and I took him out to dinner at a vegan restaurant in Chicago. While scarfing down some vegan japchae, he says, out of nowhere,

“You know? Your grandma fed me dirty swamp water to escape North Korea.”

My husband and I sit there, totally confused, before I finally say, “Wait what? What are you talking about?” While I knew, by then, that my father’s story originated in North Korea, the “dirty swamp water” detail had somehow eluded me until then.

Daddy finishes the very last of his japchae (a clean plate, despite grousing about vegan food), leans back in his seat, shuts his eyes, and begins recounting the tale. In summary:

When my grandmother was only 20 years old, she bundled up her newborn son and tied him to her back, as she began the long trek across the 38th parallel and through the mountains to meet her husband, who was waiting for them near Seoul. My grandfather had fled almost immediately after V-Day, as he had worked for the imperial police (Japan) and therefore, was at risk of being arrested or even killed. As such, it was just my grandmother and her son, my dad, who had to find away across the mountains.

But first, they would have to sneak past the men guarding the boundary between what would soon be North and South Korea. To her left, a group of armed soldiers silhouetted against the moonlight. To her right, the murky depths of an abandoned rice paddy. On her back, an infant mewling from thirst. She untied the knot at her waist and shifted the bundle until she was holding her baby in her arms. She crept towards the inky water of the rice paddy until she was knee deep, then brought some of it to the baby’s lips.

When he finally quieted, she hoisted him up as high as she could, until his face was pressed against her cheek, and sank deeper into the mud until only their heads were above the swamp. And like that, she and my father slipped past the soldiers, across the boundary, the stars a silent witness to their escape. Weeks later, she would reunite with her husband and start a life in South Korea, but that is another story.

“Wow,” my husband and I both say at the end of Daddy’s story. But, more amazing to me than the fact that this happened is that it took nearly 40 years of my life before hearing it–from either my father OR his mother, the woman who raised me.

Children of immigrants often point to the sacrifices their parents made in exchange for opportunities: going to one of the best public high schools in the country; violin, piano, and voice lessons for as long as I wanted; graduating with a college degree and getting into law school. But Daddy’s story spoke of something more basic–the profound power of a mother’s love, the role that love played for the rest of my father’s life, how it didn’t just follow him to America, but propelled him straight into its heart.

My father viewed America as the land of dreams, and here, the historical context matters. By the time my grandmother finally made it past the 38th parallel with my father still strapped to her back, the Korean War hadn’t even started. In a few years, my father would be permanently expelled from the land of his birth and instead, he would become a citizen of the Republic of Korea–a democracy that was younger than he was.

In Korea, there’s a concept called Baek-Il, which literally translates into “100 days.” It refers to the first 100 days of a baby’s life, because, as we’ve just seen, those first 100 days are the most precious, the most fragile. Thus, in Korean culture, the Baek-il is the first “birthday” celebration a baby has.

My father grew up during the Baek-il of Korea’s Republic. And those days were, indeed, fragile.

My father was 4 years old when Korea elected its first president, Syngman Rhee. Korea’s first president would ultimately be described as a “dictator” who was eventually exiled from the country. Why was he exiled? He changed the voting rules to guarantee he always won, got rid of term limits so he could be president indefinitely, he tear gassed protestors, arrested those who tried to run against him, and passed laws to discount the votes of those he didn’t like. When he was elected for the 4th time, young students flooded the streets in protest and Rhee came with his police force and tear gas grenades.

My father was 16 years old that day and he remembers running from police gunfire, hiding in the alleys as gunshots echoed all around him. One of those grenades hit a high school student, whose dead body was discovered floating on the river the next day. The image of this child’s body, gliding into the harbor… it lit a fire in the Korean people, one that could only be put out with Rhee’s resignation from office.

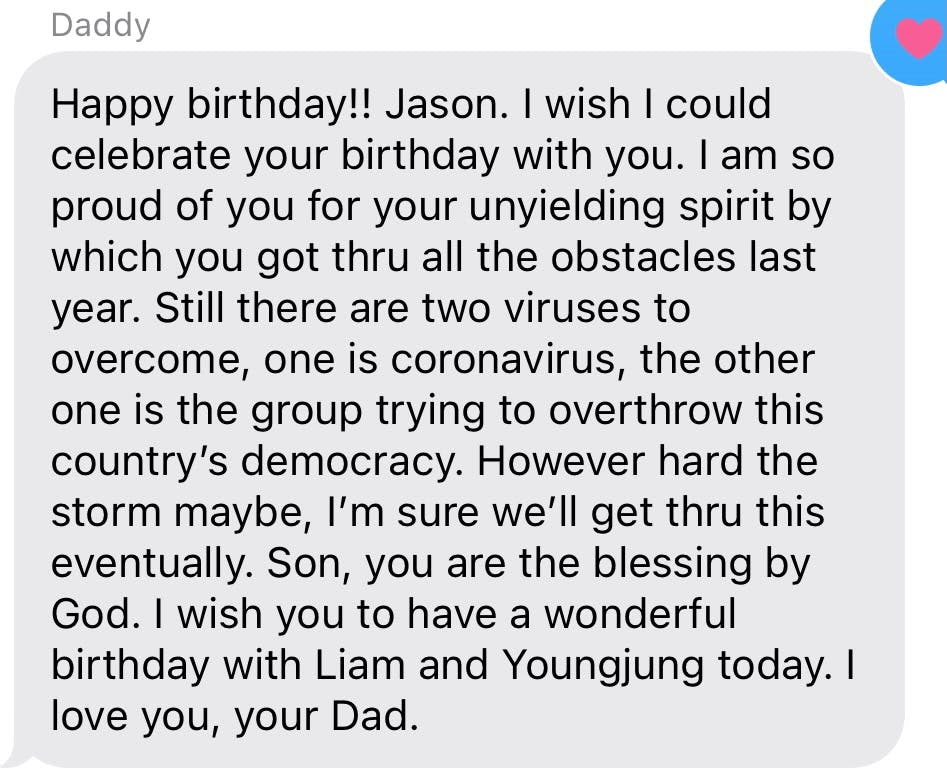

I’ve had many conversations with my father over the past few years and, perhaps because he grew up during the Republic’s Baek-il, what is more evident to me than anything is this. While his hope and belief in the truth of democracy is unyielding, that hope is tempered by an appreciation for its vulnerability.

On the morning of January 6, 2021, my father sent a group text to everyone in my family. It was my little brother’s birthday and so he wished Jaesun a happy birthday and went on to say:

I am so proud of you for your unyielding spirit by which you got thru all the obstacles last year. Still there are two viruses to overcome, one is coronavirus, the other one is the group trying to overthrow this country’s democracy.

I remember sort of rolling my eyes at that last bit, thinking, oh, there he goes, being a little dramatic, as usual.

Just a few hours later, I watched the Capitol being stormed. And I learned, firsthand, just how susceptible democracy is.

Many Asian Americans will remember 2020 and 2021 as terrible years of violence.

In 2020, the number of hate incidents against AAPI members reported to the police surged by 150%. In 2021, AAPI targeted hate shattered that already record breaking surge by 339%. Nearly 3 million AAPI adults experienced some type of racial hate in 2021. I asked my father whether in light of January 6 and the violence against Asian Americans he would ever consider moving back to South Korea. He thought about it for about 10 seconds before answering,

“No. I still prefer the United States.” When I asked him why, he explained, “Because in Korea, there is government corruption. Not like here.”

It reminded me of Alexander Vindman, the Lieutenant Colonel who testified against Donald Trump. Colonel Vindman’s father, who was from the Soviet Union, warned him against testifying, worried that his son might face life-threatening punishment for positioning himself against the sitting President. But the Colonel reassured him, that they didn’t do things here like they did in the Soviet Union, because

“Here, right matters.” Does it, though? Colonel Vindman was punished as a result of his testimony. No, he wasn’t executed, but he was forced to resign from a distinguished military career and lambasted by the same party that so often likes to tout its commitment to our troops. Sometimes I wonder whether “right” was long ago replaced by “money” or “power” or “gender” or “color” or some combination of all of these things, and if so, what good could this small space for Korean vegan recipes and stories about my parents possibly do?

Over dinner last week with a few of Anthony’s relatives in Rome, I asked whether they were proud to be Italians. They shook their heads, “No, not anymore,” said one of them, before adding, “Italians are proud only when they are with non-Italians.” The other quipped, “Italians are very proud during a football match or the Olympics!” Italy, too, has its own “issues,” dating back, well, a few millennia? “Every country has its problems,” they concluded, and I agreed. But the thing is, if I moved to Italy, as I sometimes dream of doing, they wouldn’t be my problems. I could find a small, quiet little place, insulated from and quite happily indifferent to the politics of a country that wasn’t mine, that could never truly own me in the way that America does. But even as I let this fantasy play out over a plate of vegan pasta during our penultimate night in the Eternal City, I knew that this would never happen.

That some part of me would always be fighting for that bend towards justice.

On this week’s podcast, in addition to my story, hear from scores of people as they endeavor to answer the question:

Are You Proud to Be American?

Spotify | Apple | Google

This Week’s Recipe Inspo.

Peach Cobbler Cake

This week’s Recipe Inspo is this glorious Peach Cobbler Cake, the perfect thing to bring to your 4th of July holiday get together–because there is no good reason you can’t have some cake with your cobbler!

Get The Peach Cobbler Recipe here!

What I’m…

- Watching: The Americans

- Reading: The Housemaid

- Cooking With: KitchekShop Mini Food Processor

Wherever you are, geographically or existentially, until next week, I wish you a lovely and wonderful July 4th.

-Joanne