Read Ep. 25 | Show Notes

I’m giving away two copies of Tabitha Brown’s new book, Cooking From The Spirit!

Enter below for your chance to win!

“Complaining about not achieving success despite working hard is like complaining about an ice cube not melting when you heated it from 25 to 31 degrees. All the action happens at 32 degrees.” – James Clear, Atomic Habits.

As a newbie entrepreneur, I sometimes feel as though I am walking beneath the looming shadow of failure, one that threatens to collapse over me at any moment. My fears aren’t entirely based on paranoia–according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, approximately 20% of small businesses fail within the first two years of opening. That number increases to 45% within 5 years and 65% in 10. In other words, more than half of small businesses don’t make it out alive in the first decade.

For the risk averse, these stats are enough to keep one comfortably inside the predictable framework of a steady paycheck. Indeed, it was my abject fear of failure (and disappointing my parents, something that goes hand in hand for many of us) that facilitated the success I enjoyed as a lawyer. I’ve always believed that the only way to “not lose” was to not just win, but to win by the largest margin possible. In other words, “not being last” or “somewhere in the middle” was never good enough. I needed to “set the curve” in every major endeavor I undertook, from the final exam in Microbiology 101 to my first year at the Firm.

Accordingly, I was compulsive about taking on more work, saying “yes” to every project, seeking out mentors and feedback on my work product, and making sure that every single person liked me. Towards the end of each year, I’d break down the number of hours I’d need to bill each day in order to meet my billable hours goals and only felt good about myself if I exceeded them. I also joined a practice group–the Bankruptcy and Restructuring Practice Group–based almost entirely upon the fact that no other associate in my class was interested in it, meaning that the path to partnership stretched straight out into the horizon, totally unimpeded and mine for the taking.

A compliment that I often receive is, “Joanne, is there nothing you can’t do?” While it’s a very lovely sentiment, it glosses over the fact that for most of my life, I’ve stuck to the straight and narrow, rarely letting myself deviate from the path of least resistance. In other words, at nearly every fork in the road, I’ve taken the path more often traveled, where scores of “adventurers” have not only cleared the path, but conveniently marked it with signs, guideposts, and other helpful tips designed to ensure that I make it safely to my destination with time to spare.

The Road Not Taken.

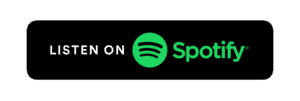

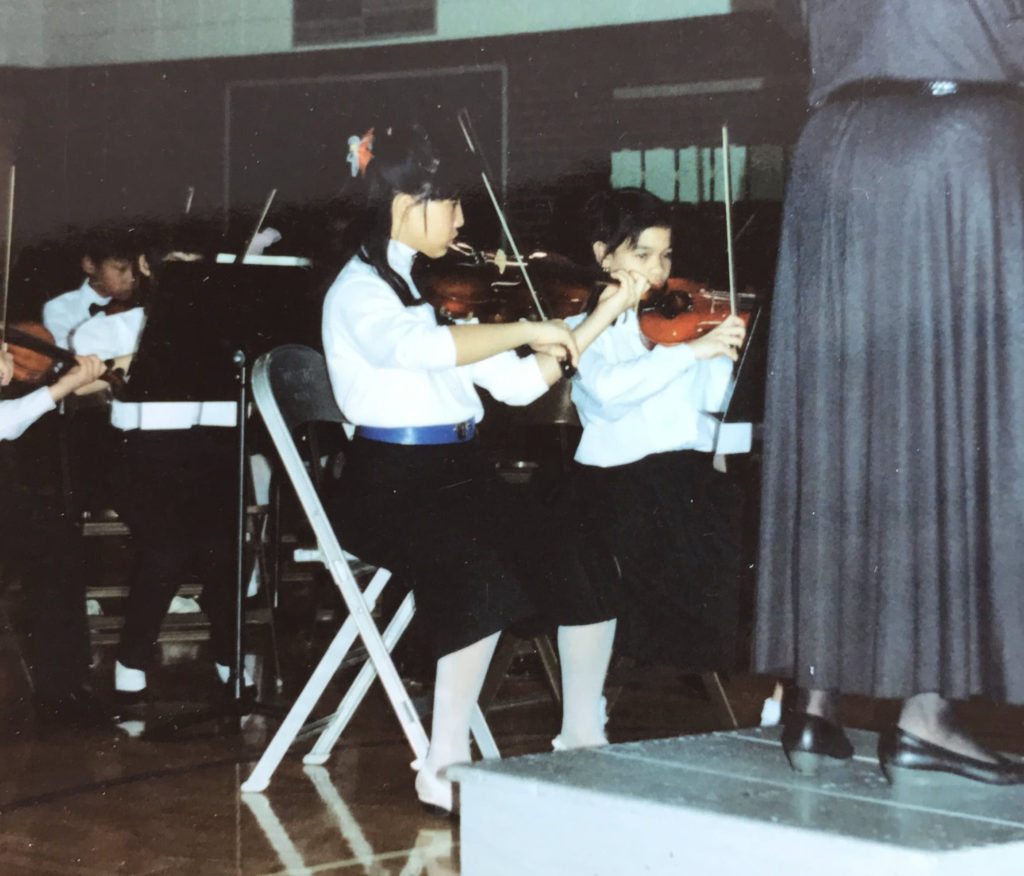

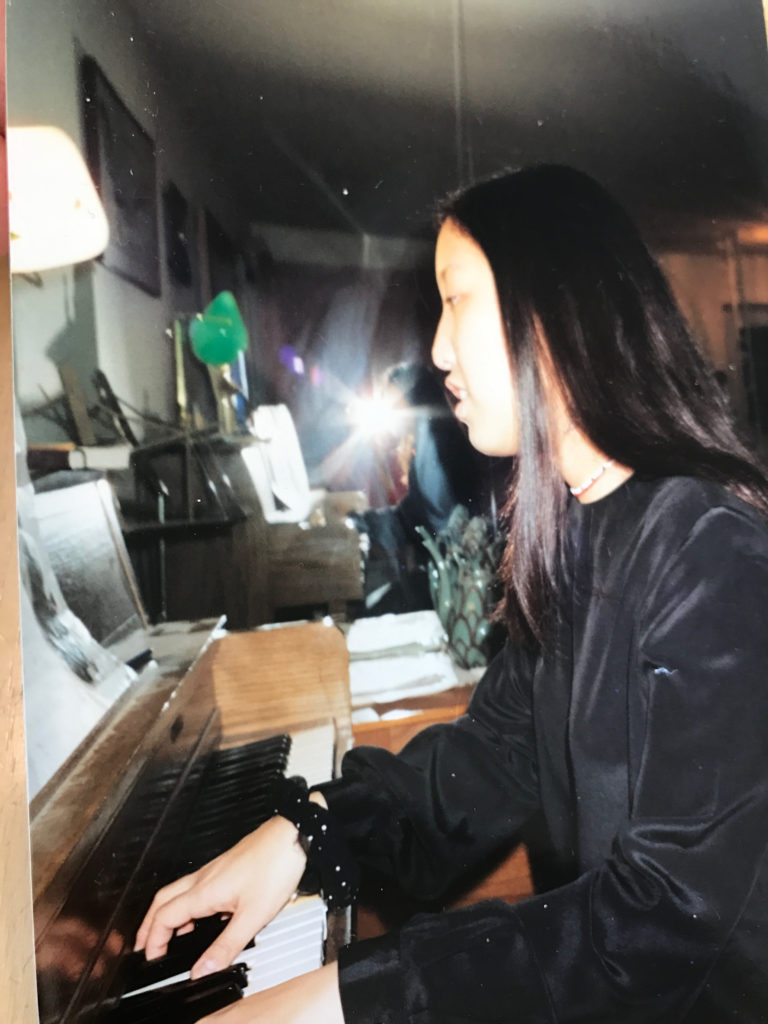

For instance, prior to selecting my legal career, I wanted to be a singer. As it happens, my father’s side of the family is quite musical. My aunt (my father’s younger sister) was a professional singer back in Korea, and my father himself clearly possesses a talent for music (he taught himself how to play Bach by reading a book!). But it was my grandmother, my father’s mother, who instilled in me a love of music for as long as I can remember. She would sing at night, teaching me and my brother the words to her favorite hymns while we lay in bed, until all of our voices–Hahlmuhnee, me, and my little brother–wove together and spiraled past the glowing street lamps and out into the stars. Hahlmuhnee always sang with the authority embedded in those who believed in God because they must, and as a result, her keening vibrato revealed a heart festooned with an unwavering commitment to piety and faith.

I guess, in some ways, I wanted to sing because I wanted to be more like my grandmother. But it was also because everyone loved me when I sang. “Aigoo, she has such a beautiful voice, your daughter!” They’d praise me at church after a choir solo, and my mother would nod her head and cover her mouth as she laughed daintily at the compliment. “Really? She hardly practiced at all!”

Over the years, I added piano, violin, and even guitar to my repertoire, but I knew that my talent for singing came naturally, while the others did not, and that most others couldn’t do what I did with my voice. I started taking voice lessons when I was 13 years old (I was told to wait until after puberty) and teachers and students alike confirmed, “Wow, you can sing.” I routinely secured solos in every choir I auditioned for, singing at Orchestra Hall with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra when I was only 15, and I landed the lead in the school musical both years I was allowed to try out (my parents kept a strict rein on my extracurricular activities, and singing/acting were definitely not “tier 1”). By the time I set my sights on college, I had a host of conservatories on my short list of dream schools.

But it is exactly at this point in the road that I veered. Hard.

First, during my senior year, I didn’t land the big solo at the annual senior recital, one that I’d sort of taken for granted I’d get all four years of high school. That honor went to my friend, Sarah (who, to be honest, was incredibly talented and deserved it).

Second, I didn’t get into every conservatory/music school I auditioned for. I got into some (Oberlin and Carnegie Mellon), but I didn’t get into the one closest to home, Northwestern University. [Sidenote: If I had gotten into Northwestern, I would have enrolled in the music school at the same time Anthony was there for his Master’s degree, right before he won the Naumburg International Piano Competition. I always get a kick out of imagining whether we would have hit it off in quite the same way if we’d met back then…!]

Third, my parents made it abundantly clear to me that if I chose to major in vocal performance only in college, I’d be doing it on my own. Therefore, I had to find a program that allowed me to double major in two totally unrelated disciplines (they reluctantly agreed to support my pursuit of a BA in English). At the time, this was not as common as it is today and often required that I build two separate curricula from scratch.

My parents’ unwillingness to support a career in singing was a hurdle, sure. But probably not one I couldn’t have cleared with the same sort of determination I had when running the 50 yard dash in 5th grade

The barrier I couldn’t overcome, though, was the self-doubt that suddenly emerged when I was no longer getting all the solos, when the doors weren’t all swinging wide open for me, when the world “out there” seemed unacquainted with, maybe even indifferent to, my track record.

i.e., When I got my first, bitter taste of failure.

The Road Very-Well Travelled.

Who knows what would have happened had I pressed ahead and pursued my love of singing? In my head, I saw myself as a starving artist, hopping around from audition to audition, waiting tables at some dingy diner in NYC, rarely gracing the stage and even then, only as part of the background, never as the star I’d dreamt of being virtually my entire life. Throughout college and even years later, to the extent I’d look back with so much as an ounce of regret, I’d remind myself that had I gone to New York and pursued a career in singing, I would never have gotten together with my first husband (the then “love of my life”) and therefore, I’d indisputably made the “right choice” in choosing to stick with a good ole’ Bachelor of Arts, followed by a career in Big Law.

Speaking of lawyering, by the time I graduated college, the instinct to prevent failure was honed to a sharp point, one that jabbed at me every time I scoured the classifieds for the words “now hiring” or “entry level.” After one year of voice lessons with a vocal performance major in college, I’d completely dismantled my melodic dreams and replaced them with the stodgy, brown-brick durability of “adulting.” I needed a solid 9 to 5 that came with a decent paycheck, good benefits, and respectability. After a few months as a resume writer, I decided to try for law school–not because of any burgeoning desire to enter the hallowed halls of justice. I chose law because it was the least daunting option of the three degrees I considered: MD, MBA, or JD. I knew I’d faint at the sight of blood and that I hated selling things. That left just law. The fact that I liked to argue a lot (according to my mom) was just a bonus.

Why did I leave myself with so few career options? Because each of them had a pretty self-determined path, with very little room for discretion and thus error–particularly in law. While it was possible I wouldn’t be able to clear all the hurdles set out in front of me, at least I would know exactly where each of them lay and just how high they’d be. First, take the LSAT. Then, get into law school. Do well enough in law school to get a summer internship, followed by a full-time offer. Pass the bar exam. Do well enough at the Firm to not get fired and one day make partner. The path was so freaking clear and detailed to such a degree of granularity, it was like I could see every blade of grass that dotted the road from where I stood all the way to retirement. Armed with that level of information so far in advance, I could give myself every chance at being able to reach the finish, relatively intact and with a very nice 401k to boot.

With each passing obstacle, I’d barely give myself a minute to celebrate. When I got into my #1 choice for law school, I did the happy dance with my then boyfriend (now ex-husband) in the corridor outside the small legal office I “paralegalled” at during the summer before classes. When I received a full-time offer from the Firm, I stood outside my parents’ Wilmette house, put one hand on the telephone poll at the end of our driveway while turning the other into a fist that shook at the sky like Rocky. When I passed the bar, I let out a huge sigh of relief and laughed as I watched my Dad jump around in his pajamas at 3 in the morning (when the results finally loaded on the ARDC’s website). And when I finally made partner, I made a reservation for one at the posh restaurant of The Peninsula Hotel, enjoyed a tray of British scones with fresh clotted cream, a basket of piping hot French fries, and a bottle of Diet Coke, before heading back to the office.

I told myself that “this is the dream!” “You’ve done everything you’re supposed to do!” “Your parents are so proud of you!” It was so much easier to believe that all the “wins” were authoritative confirmations that I was on the path I should be, that I was meant to be.

But here’s the truth:

It wasn’t the blinking lights of success that beckoned me forward.

Nope.

Failure just never quit chasing me.

My Biggest Failure in Life.

The fear of failing, and all that failure would entail–shame, embarrassment, guilt, waste, and, most agonizingly, being alone–kept me inside of a relationship that was toxic nearly from the get-go. As evidenced by how quickly and angrily I dismissed my parents’ well-founded fears about my impending nuptials, I channeled all the single-minded, fear-fueled determination that catalyzed my career path into my “love path.” But unlike my career, my marriage was a big, honkin’ failure.

But I can think of no more profitable failure in my entire freaking life.

One of my favorite quotes about failure comes from David Goggins: “In every failure a lot of good things will have happened, and we must acknowledge them.”

There’s a temptation to call my first marriage a “success” or at least, “not a failure,” but let’s be real, here. By definition, marriage is supposed to be “until death do you part.” I walked down an aisle lined on either side with big red flags and chose to see right past them, repeating to myself “love is enough.” We made it about 8 years before we separated, 9 years before we divorced. Of all the choices I’ve made in my life, getting married that first time around remains the most susceptible to regret.

But, as Mr. Goggins suggests, acknowledging the good from that failure is important. According to another David, David Epstein, “The more confident a learner is of their wrong answer, the better the information sticks when they subsequently learn the right answer. Tolerating big mistakes can create the best learning opportunities.” One of the most important “good things” that came out of my mistakes was finding a romantic partner who would not only go toe-to-toe with me, but one who would never feel threatened by my ambition or drive. However intolerable my mistakes seemed at the time, the lessons they taught me were, indeed, indelible, without which, it’s entirely likely I would not be sitting here today, happily married to the man I consider to be my partner in the truest sense of the word.

Perhaps more important, though, other than learning how not to fall in love, as I’ve talked about before, my failed marriage offered me an opportunity to rediscover myself. And by that, I don’t just mean the person I used to be before I entered that relationship, but the woman who emerged from it.

Last week, I talked about how I’ve started using an app that allows me to journal via voice note, and how this has facilitated a strange, but surprisingly pleasant “friendship” with myself. It’s fostered an unusual sort of kindness, one that I can’t ever remember extending towards the girl I see in the mirror. And there’s a distinct sense of fondness I bear for the young woman who walked out of the front door of her townhouse in Wheeling, Illinois, because I can remember how fragile she felt, how much her heart shook as she gripped the handle of her suitcase and told herself that if she had the strength to walk away from a marriage in shambles, she’d someday find the courage to erect a life of purpose.

Strategic Failing.

While there’s a lot of good that comes from failing, I don’t think anyone would advise you to start something with the goal of failing. That said, I do think there’s value in “strategic failing.” I’ve talked about this before in the context of dream chasing, but it bears repeating that for dreams to truly bloom, you need to plant them in safety while also giving them time to grow. Sure, there are plenty of legendary success stories out there about people who threw caution to the wind and went all in on their dreams with zero safety net or contingency plan, while mortgages, healthcare, and food on the table hung in the balance. But what we rarely ever think about, much less hear about, are the many millions of dreamers who shelved their passions because they were–understandably–too frightened to fail. If we tell people that the only way to make their dreams come true is to give up everything that makes them feel safe (a narrative I hear too often pushed on Shark Tank), can we blame them for not even trying?

Call me pedantic, but I think there’s value in removing some of the pressure to go “all in,” and say instead, “bet reasonably.” It’s far more “tolerable” to make mistakes when you have some money set aside in savings, a job that still pays the bills, or a “Plan B” that’s ready to be deployed if Plan A goes south. Given my serious aversion to failure, gathering data and building myself a safety net was the only way I could develop the gumption to finally say farewell to all the things that, until that point, provided me with financial security and the respectability I’d craved. While that certainly doesn’t exclude folks who don’t have a sturdy safety net from “going after it,” it also doesn’t mandate that you risk losing it all.

I’m not ashamed of the fact that I spent several years nursing my “hobby” while I worked a full time job; that for several years, I literally laughed at people who suggested I might make a living from recipe development and food blogging; that even when I was offered a lot more money than I thought was possible to write a book containing my “hobby,” I still didn’t think seriously about turning something I loved to do into a career. I felt I had too much to lose, at the time, but in retrospect, it was simply that I needed more time to get comfortable with the possibility of failure.

Towards the end of 2020, less than a year before my book was due to be published, I went out for a run and once more, went through the numbers (I like doing math while I run–it passes the time). By “the numbers,” I mean all sources of reasonably foreseeable income from The Korean Vegan. It was an exercise I’d repeated hundreds of times by then, but I did it again with the hope that this time, it would somehow give me the reassurance I’d yet to feel about the possibility of leaving the partnership at my firm. When it didn’t work (surprise!), I tried something else: I asked myself,

“Ok. If everything goes to shit and you’re literally living out of a cardboard box, Anthony has divorced you, and you’ve got nothing left, then what happens?”

I continued to put one foot in front of the other on the lakefront path, huffing and puffing but with my heart rate steady, and said to myself,

“I’d figure it out.”

Sometimes, the time needed to build your safety net isn’t necessarily for saving more cash, analyzing more data, or coming up with a backup plan. It’s the time you need to realize that the most enduring safety net in all the world…

Is you.

Ask Joanne.

In case you’re wondering whether I still sing, the answer is yes. But…to a much more discriminating audience.

I’ve been learning Indian classical music for about nine years now (I’m currently a sophomore in high school) and for as long as I can remember, everyone’s told me I’m a good singer. I just *got* subjects, was naturally good at pretty much everything I wanted to do. Spending years like that kind of made my self-worth dependent on how “good” I was at things, so when things naturally became harder, I hit a roadblock. Earlier this week, I auditioned for a higher level of chorus at my school, and was reassured by everyone again that I was a great singer and would definitely make it. I didn’t. It’s beyond mortifying that I gave my all in front of a group of people who see me in the hallways at school every day, and was still one of the only people to be rejected. This is really dramatic, but it feels like someone ripped a piece of me out, put it under a microscope and inspected it, and then pulverized it and threw it into an incinerator for good measure. How do I convince myself that I’m more than my failures? -Arria

Arria,

I don’t think you’re being overly dramatic at all. As we discussed in last week’s newsletter, it’s very easy to fall into the trap of defining ourselves based upon how others see or value us. Thus, when that perception shifts, unexpectedly, it’s not surprising that we start pondering some of life’s most fundamental (and somewhat distressing) questions: “Who am I?” and “What does it all mean?” It’s easy to become particularly susceptible to this when you’ve yet to come up against your Goliath and thus haven’t had your sense of self tested in any challenging way.

The instinct to define yourself by your “failures” is, once more, ceding to the habit of being defined by how everyone (in the school hallways, in chorus, or even at home) sees you. Let’s imagine that all those folks can be embodied into a single person–the person who represents all the people who thought you’d make it into this higher level chorus and who are now purportedly realizing that you’re not as good as they had thought (I’m not saying that’s the case, but let’s assume so for this exercise). Give that person a name and then tell them, “Hey [insert name], thanks for your input. I understand where it’s coming from, but I’m going to need you to shut up for a minute. Ok thanks.”

Then, ask yourself the following:

- Do you think you’re still good at singing? Presumably, over the years, you must have learned something about what good singing is and what good singing isn’t. Lean into that knowledge and experience and ask yourself, honestly, if something has suddenly changed and you’re not actually the singer you thought you were. Chances are, you know, deep down, exactly how good you are.

- Do you enjoy singing? If so, list all the things you actually like about singing, separate and apart from receiving praise for being good at it. What kind of music do you enjoy? Do you enjoy Indian classical music or is it merely the type of music at which you excel? Are there any other instruments you like, perhaps even more than singing?

- What do you enjoy doing that has nothing to do with music? Do you like reading, writing, dancing, running, video gaming, cooking, drawing?

- What are you good at besides singing? Are you a good listener? Are you skilled at problem solving? Do you have a knack for making friends? Are you the person that people go to when they want to have fun, when they need a helping hand, or when they want a shoulder to cry on?

- And…what are you indisputably bad at? Are directions not your thing? Do you get lost easily (uh… I might be projecting here…)? Do you burn things in the oven more often than not? Are your essays always full of typos? Do you find yourself losing your patience over small things? Or maybe letting people walk all over you, even when you know you shouldn’t?

As I’ve advised in the past, my recommendation is that you not just ponder these questions, but write out your thoughts. It doesn’t have to be coherent or even legible–you’re not going to share it with anyone. Or, maybe, it might even be interesting to record your answers in your own beautiful voice. The point is this, Arria: exploring the outer bounds of these questions will force you to start sketching the boundaries of you, getting very familiar with the line that separates you from everyone else in the world. Because at the end of the day, you and I both know that whether you make this choir now or later doesn’t really matter in the long run if you are able to come back to yourself each day and say, quite confidently,

“I really rather like who I am.”

Wishing you all the best.

I’m giving away two copies of Tabitha Brown’s Cooking From The Spirit. Enter below for your chance to win!

Updates/Random Things (Show Notes)

- GIVEAWAY ALERT!!! This past week, I got to see the legendary Tabitha Brown at the final stop of her Cooking From The Spirit book tour. Because I ordered her book as soon as it was announced (I am that kind of fan), I now have two extra SIGNED COPIES to give away!! Registrants from all over the world are welcome and the winners will be announced in next week’s newsletter. Enter above and good luck!

- What I’m Watching: As I’ve mentioned before, Anthony is now studying, hard core, for an Italian language test this December in Rome. Accordingly, we’ve decided to rewatch some of our favorite Italian dramas. On deck at the moment is Il Proccesso (The Trial). A legal drama centered around the narrative of a young prosecutor who is attempting to build a murder case against the daughter of a wealthy (and well connected) businessman, the show takes you on a total rollercoaster without feeling overdone or manipulative. It’s 8 episodes total and each episode is less than an hour long. I highly recommend it!

- Signed Copies of The Korean Vegan Cookbook: Last week saw the 1-year anniversary of The Korean Vegan Cookbook! I can’t believe it’s been a full year since the book was published–it feels like just yesterday! This past weekend, I went to Now Serving LA–a bookstore that features only cookbooks–and signed their entire stock. If you’re interested in getting a head start on your holiday shopping, you can order your signed copy here for delivery!

- What I’m Cooking: In case you missed it, this week I made Korean radish kimchi stuffed onigiri or “rice triangles” that I subsequently stuck in the air fryer for a little “crispy crisp” on the outside. Anthony has proclaimed this to be among one of his favorites. It’s so easy to make and so yummy–I think you’ll enjoy it too! Make sure to check out the TKV Meal Planner for the recipe!

Parting Thoughts.

There’s a powerful Buddhist precept that provides “desire and ignorance lie at the root of all suffering.”

Now, obviously, you can’t get rid of all of your desires. For example, the desire to stay alive is very important! But this concept is directed at those wants and yearnings that, at the end of the day, bring us little joy. Isn’t it funny how badly we want things that do so little for us? I’m reminded of how, when I was very young, I was obsessed with collecting as many stickers as I possibly could for my sticker collection. I would literally go to bed each night, clutching my sticker book to my chest, and dream of winning sheets and sheets of pastel colored stickers shaped like unicorns, Care Bears, and glittering stars. I got it into my head, in that way that children sometimes do, that everything in my life would somehow click into place if only I could fill in every last square inch of my sticker book with more stickers. But when I finally did and subsequently leafed through each heavy page, I realized that the stickers, upon closer examination, were cheap, already beginning to wrinkle and fade, and that this collection that I thought I’d be so very proud of was, in fact, not very meaningful at all. And just like that, I never cracked it open again.

How many of you can relate? How many of you have seen this exact same thing play out with one of your own little ones?

However many sticker books we’ve thrown by the wayside, the instinct often remains intact into adulthood. Replace sticker books with designer bags and shoes (I’m definitely guilty of this one), that massive bucket of ice cream that’s screaming at you from the fridge, or even that person you know isn’t good for you, but sometimes makes you feel good for a few hours (or minutes). Don’t get me wrong: all of these things can actually help soothe you, and they have their place in the world (no one is going to take my Ben ‘n Jerry’s outta MY house!). But these “wants” can sometimes mask a much more critical desire, one that should not go unaddressed for too long.

When I was working as a mid-level associate at the Firm, I would award myself periodically with “retail therapy.” Retail therapy is effective–it can make you feel better not just when you buy the thing, but every time you look at the thing. I used to take a break every now and again from work just to stare at the pretty, pink Prada bag I’d just acquired and it would literally make me feel better, like I would tell myself, “Oh, this soul sucking job that’s keeping me at my desk at 11:37 pm while normal people are at home either asleep or watching tv? It’s all worth it because of this Prada bag.” The fact that I could stand aside and watch myself believe this lie told me all I needed to know:

My soul was hungry.

And I was feeding it junk food.

When we think about “successful” people, they too often tend to look alike: rich, influential, with fancy cars, private jets, and famous friends. And when we see this image of “success” depicted on social media, that same “sticker book” instinct can threaten to rear its ugly head, leading us to think that we need those things too. How easy it becomes to fall into that rat race, when the accoutrements of “success” become the goal themselves. But when you step back for a moment and ask yourself, “is this really what success looks like for me?”

For me? Being able to wake up on a Sunday morning, enjoy a cappuccino with Anthony, while peeling apart the perfect vegan croissant in preparation for our daily Wordle comes to mind.

Wanting financial security isn’t the same thing as wanting to fly in private jets, so, ask yourself, assuming you have enough money to live comfortably, what feeds your soul? What gets you excited each day? What motivates you to be a better person? What challenges you to grow, and what kind of impact do you want to leave on this one precious planet of ours?

In other words…

Consider exchanging success for purpose.

– Joanne