Read Ep. 13 | Show Notes

Subscribe Below to Receive the TKV Newsletter in Your Inbox

“Ok. Omma. So, I have some news.”

“Okaaaaay,” she says into the phone. I can see my mother, now, even as I sit there on the floor of my kitchen, back leaning against the island as I hold my cell loosely in my hands. I imagine the shape of her mouth as her lips wrap around the “kaaaay,” her small hand gripping her iphone just a little tighter as she folds one arm so that she can tuck her fingers into the crook of her elbow. She laughs, a little, a sort of awkward ellipses as she waits for me to fill the silence.

“So, I’m sure you saw this coming, but, I’m going to quit being a partner at the firm and just do the Korean Vegan full time. And…, I’m moving to L.A.”

…

“NO!”

It isn’t the “oh noooooo, honey, you don’t want to do that” kind of no.

It is the “you can’t have ice cream for dinner” kind of no. A “you can’t have that Barbie because I just bought you one yesterday” kind of no. A “no new lego set for you until you learn to clean up after yourself” kind of no.

“What do you mean ‘no’?” I query, with an awkward little laugh of my own.

“NO.” And then in case I missed it, “Nooooooooooo.”

That last one comes out like more of a moan than a word.

Over the next 15 minutes or so, I proceed to have what is probably the most uncomfortable [read: unpleasant] conversation I’ve had with my mother in over a decade.

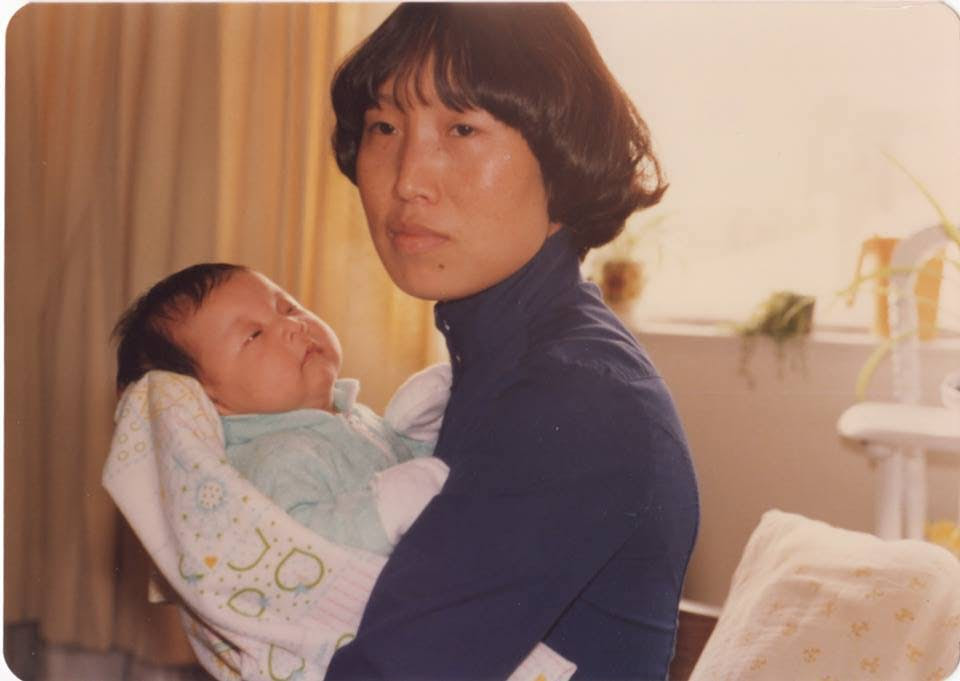

I don’t think Sunny really wanted to be a mom.

I always had the impression that my mother wasn’t happy as a mom, that she sorta regretted having children, even getting married. She often talked about how she wished she were single, childless, living in her own small apartment, driving her shit-brown Nissan Sentra without having to share it with my dad. There was a part of me that was afraid of this “Sunny,” the one that would be indifferent to her never-born children as she lived her best life. But there was another part of me that admired her, wanted to be her, too.

Sunny was reading a novel while giving birth to me. Maybe that’s why I love books so much—the way they smell, particularly if they’ve been yawning in the sun for long stretches; how the weight of its individual pages say as much about its personality as the state of one’s fingernails. Omma taught me to love the wrinkles that cracked the spines, the discreet “swish” of each turn of page, the smudges staining my fingertips when I finally put a book down.

I picture Sunny reading her book on the hospital bed, her belly poking up from beneath the bedsheets, undeniably irritated at the thing that was pulling her away from what she loved.

Growing up thinking your mother doesn’t want to be a mother (and thus your mother) makes everything uncertain and tenuous. In my case, this situation was made even worse when the language and cultural barriers sprang to life between us as soon as I started learning English in kindergarten. Given the amount of time she spent away from home working at the hospital, Omma always seemed out of reach, as if ensconced in her own bone white Ivory Tower. When we were little, her days off from work were our favorite days. My brother and I would cleave to her small body like little monkeys on a tree (what she used to call us, “my little monkeys”). “Let’s play, Mommy!” we begged, as her exhaustion painted itself across the delicate features of her face, visible to me even at 5 years old.

Oh, the fights we had…

When Omma was angry, she remained aloof, cool. Don’t get me wrong–my mom could yell with the best of them. But her tirades were rarely flailing or saddled with the trappings of frustration. Rather, they were precise, incising, cutting, and exponentially more hurtful than anything my father could dole out even during his most explosive, yet clumsy, outbursts (ask me about the “rice rage” incident sometime…). There was always a sense that she wasn’t just disappointed in me (for stealing something from my friend’s house, for lying to her about upending the sewing kit, for spelling “Australia” wrong for the 70 billionth time), but that she was also disappointed in how her life turned out. She possessed a talent for making me cry instantly, even when I was in college, something I grew to hate about myself. Why couldn’t I be cool and cutting like her? Why did I have to be weak in front of the one woman who was the exact opposite? Her superpower was going days without talking to me, keenly aware that I couldn’t bear knowing she was unhappy with me for even one minute.

It was tempting, at times, to apologize even when I didn’t mean it, to simply say “sorry” to puncture the unbearable coldness she wrapped herself in when she grew mad. But I could never bring myself to do it, even when I upended the sewing kit. I don’t know from whom I inherited this trait (maybe from her!), but I had this rigid sense of justice that prevented me from giving in, even if it allowed me to bask in the warmth of my mother’s approval and love. It was always so imperative to me that we were on the same page about everything, because I didn’t want to live on any other page but my mother’s. Or, perhaps more accurately, I wanted, very desperately, for her to live on mine.

Luckily, much of the fighting stopped once I got into law school. At that point, it seemed I’d finally proven myself to her–or so I thought. During my 3L year, I stayed in bed a little late one morning. My first class wasn’t until 1 pm and it was my final year in law school. I’d already earned a full time job offer from a prestigious international law firm and graduation was only a few short months away. But on her way to work that morning, she waltzed into my bedroom and and treated me to a trademark Omma tongue-lashing, laced with words like “lazy” and “irresponsible,” because I’d elected to sleep in that morning instead of hitting the books as I typically did before class.

Omma’s disappointment in me for staying with my ex.

My mother saved the sharpest barbs for years later, when I would come to her after yet another fight with my then husband. Month after month after month, I’d show up on her doorstep, sometimes during the middle of the night, tears caking my face. She’d open the door and before saying, “hello,” she would utter just one syllable:

“또?”

Which translates into:

“Again?”

Somehow, my 87 lb 4’11” mother was able to pack into that tiny little syllable enough power to knock me out. Because I knew she wasn’t talking about my husband.

No.

All the contempt she injected into that word was meant for me.

My mother once told me about a time in college when this nice young man wanted to date her. She wasn’t interested. “He was too nice,” she’d say. Despite hinting to him that it wasn’t ever going to happen, he was persistent. That year, Sunny grew very ill and had to be hospitalized. He came to visit her every day, sat by her bed and took care of her when she was too weak to take care of herself. Again, she’d say at this point in the story, “He was so nice!” But, one day, when she was finally feeling a little bit like herself, she opened her eyes to find him sitting at her bedside, as he did day in and day out. She looked at him straight in the face and said, “when I wake up next time, I don’t want to see you sitting there. Because the sight of you makes me sick.”

I remember being totally awestruck with my “cool mom” when she first told me this story. Awestruck and a little horrified that she could be so cruel. This was the “Sunny” who’d always simultaneously terrified and inspired me, the ferocious young woman who would never stand on ceremony at the cost of her pride. In retrospect, I realize that this “nice young man” was anything but “nice,” and was, instead, weaponizing his “kindness” in order to manipulate my mom into thinking she “owed” him her love. The fact that she could detect this sort of sliminess in a man in her early 20s still leaves me slightly agog at her power.

I thought of this story almost obsessively, the “Sunny” who was able to tell a man to get out of her life with such disdain, when I remained stuck in a relationship with a man who so obviously didn’t know my worth (until it was too late). How was it possible that I inherited my mother’s bowed legs, her perfect lips, her love of books, but failed to acquire her self-respect?

You see, my mother’s problem was never that I showed up on her doorstep. It was that I always, always, always went back to him.

Sometimes with my head held high. Sometimes, on my knees.

But every single time–

I went back.

“Why do you always go back?”

Our conversations about my marriage were likely getting boring for Omma. It was always the same:

“Why do you always go back?”

[shrug shoulders]

“I dunno.”

And then, a few seconds later,

“I’m just not like you.”

[to the deep disappointment for both of us.]

Once, Omma tried to literally bribe me into not going back. She took me shopping at the local mall, bought me a pair of trendy new sneakers and a shirt to reward the willpower that kept me at her home for a whole 3 days after another explosive fight with my husband. But the sheen of my mother’s pride eventually faded, as I sang the same, grating chorus that was my love life, even if a little later than expected, and crawled right back into his arms. She knew that in doing so, I was not – nor likely ever would be – the cool, aloof woman she’d worked so hard to nurture. I was weak and I went groveling back into his arms, begged him to forgive me for somehow making him hurt me, and agreed that it was “all my fault” as I buried a thistle of rage deep, deep into the chambers of my heart.

As I walked out her door, she yelled, “next time, don’t bother coming here. I don’t want to hear it if you’re going to be so weak,” shame and derision dribbling off her words.

As I write this, I wonder why I couldn’t behave with him the way I did with my mom. With her, I never gave in. I raged against the icy block of marble that was my mother until, eventually, she softened. But with him, I would always dissolve. His love was a drug, one I’d grown addicted to despite everything Omma did to wean me off of it.

Sunny’s Story.

As I’ve written about before, Sunny nearly died when she was only 1 year old. The Korean War had just started in her province in North Korea and her parents ran out of food on their way to the Yellow Sea, where they were told a US Navy ship would take them to safety. By the time they got on board, my grandparents decided to drop my mother into the churning water beneath them, instead of watching her die from starvation. Luckily, a couple of American GI’s caught them in the nick of time, handed Sunny a Hershey Bar, and, as she often repeats to me, “saved [her] life.”

I sometimes wonder if Sunny’s near-brush with infanticide bothers her. When I ask her to tell me about the time Hahlmuhnee almost drowned her in the sea, the gleam of pride in her eyes is unmistakeable. “Oh, you mean the time Grandma tried to kill me?“ as if she’s saying “Oh, you mean the time I finished the Chicago Marathon?”

“This is my favorite story,” she always begins.

It’s impossible for me to reconcile this calloused woman with the mother I wanted so badly. Omma once told me that in summer, the ground was smothered in persimmon blossoms. “I picked them off the floor and I ate them. They tasted sweet and pretty. I thought I was getting pretty. Like the flowers, after eating them.”

This was the mother I wanted–the one who picked persimmon flowers off the ground and ate them to be pretty.

But instead, I ended up with a mother who regretted eating those persimmon flowers because they made her daughter soft.

My mother’s family crossed the 38th parallel and landed in a small valley along the southern fringe of South Korea called Suk Bong Rhee, Chun La Namdo. They were referred to as “Korean War Refugees.” They were homeless. My grandparents traveled from house to house, begging for scraps of food and a place to sleep for the night. When they were lucky, they dug up leftover vegetables from recently harvested fields to supplement their daily meal of watery porridge.

Eventually, my grandfather was able to find a job as a janitor at a local middle school. He was good with his hands—he made kites for my mom and whittled tops for the neighborhood children. They were always poor, though.

Still, my mother remembers her childhood with great fondness. Poverty and war are powerful, yes. But so is the taste of fresh berries, picked by your own hand along the ridge of a mountain lumbering over the hot months of summer like a drowsy silverback. Or the smell of barley heads snipped off their willowy bodies and roasted over an open flame beneath a blanket of preening stars. Or the sight of the moon, lofty and alone at harvest, sending a vector of glittering laughter straight into that spot on my mother’s back. Or the sound of your own heartbeat, while you hold your breath hostage behind the palms of your hands because it’s the only way to stay completely still during hide-and-seek.

Sunny’s becomes the family “son.”

My grandfather was the only son of an only son.

And because of this, my grandmother knew (i.e. it was made explicitly clear to her by her in-laws) that her most important job was giving birth to a son.

Thus, though they were homeless and jobless, with two little mouths to feed, my grandparents continued to add to their family even during the war. My grandmother buried two more daughters alongside one of my mother’s older sisters, after escaping North Korea. For years, my grandmother gave birth to daughters instead of a son, and soon, the entire village called them the family of “Seven Princesses.”

Sunny, worried that her mother would eventually die from a difficult labor or miscarriage, told her parents that she would be their “son,” and that she would take care of them when they were old. She was too young to know what this meant, but old enough to understand its weight. Sunny’s apprenticeship as the family “son” began when she was just 8 years old. Her mother took her to Seoul to stay with her father, who lived there most of the year due to work, and in his spare time was building a house for the family. My mother remembers, “It was a very boring and hot summer. There was nothing for me to do except walk around the hills and pick wild flowers and berries. The flower I loved most was ‘Evening Primrose’—it was light yellow like light and opened up after sundown.”

That summer, and for the rest of the year, Sunny was her father’s “little helper.” She eventually learned how to cook over a fire (they were living in a tent) and even lent a hand with small tasks around the house my grandfather was building. Her apprenticeship prevented her from enrolling in school for an entire year. Despite falling a few years behind, she still managed to pass the entrance exams for middle school. There, she met Miss Young, the beautiful English teacher who taught her how to say, “My name is Sally. I am a girl!”

It could be said that Sunny’s journey to Chicago, Illinois began when she met Miss Young, when she proudly declared, “My name is Sally! I am a girl!” She was an excellent all-around student, not just in English, and garnered the attention of teachers who would ultimately come out of pocket to support her education. Every year she’d show up to class and find school supplies inside her desk, a pristine notebook, a box of new pencils. It turned out that her homeroom teacher, Mr. Park, slipped them into her desk at the beginning of each term. Years later, Mr. Park would rescue her from an underwear factory—where she worked for one week after her parents informed her that they couldn’t afford to send her to high school. Sunny had scored in the top 7% of her class on the entrance exams and Mr. Park had her story published in The Korea Times—Korea’s first English daily newspaper. Shortly after its circulation, a “General Morris” paid for my mother’s high school tuition, allowing her to graduate with a high school diploma.

After high school, Sunny started working as an embroidery designer in Seoul (once again in the undergarment industry) because she couldn’t afford to go to college. When Omma tells me this part of the story, it’s clear that she thought that this would be her life–making pretty underwear for those who could afford them. But, two days into her budding career as an embroiderer, she received a call from her high school English teacher, Miss Oh. Miss Oh, frustrated with what she viewed as a waste of talent, suggested that Sunny look into the National Medical Center’s College of Nursing. The Center offered a three-year scholarship for promising students, a guaranteed job offer upon graduation (subject to passing the board exams), and even hinted at a potential ticket to the United States on a nursing visa. Sunny discarded the needle and thread and was soon on her way to starting what would ultimately be a 45 year career in nursing.

Omma likes to attribute her success to the generosity of the Mr. Parks, Miss Ohs, and General Morris’s of the world, where she is simply the lucky recipient of pencil cases, scholarships, and the like, as if she never had to fight for anything. There is no disputing that, but for the incredible kindness of the aforementioned angels, my mother would not be where she is today. But, like many people, she often discounts—even to herself—the role she played or the fights she fought.

Sunny gets into a fight on the way home from school.

Believe it or not, Sunny got into an actual fight once. Yes, a physical altercation.

In 2nd grade, I befriended the only other Korean girl in my class, Sally. She’d just moved into town and lived in a small apartment a few blocks from our Skokie house–just close enough to ride my bike there when I got older. We instantly became “best friends forever,” trading unread copies of Babysitters Club, Sleepover Friends, Sweet Valley Twins. We even made a poster with the words “BEST FRIENDS,” dotted with glitter and some of the most prized specimens from our joint sticker collection.

Then, one day, in 3rd grade, she stopped talking to me. To this day, I have no idea why. Despite asking her in every way I could, Sally never ever told me what I’d done to lose my status as BFF.

As you can imagine, I was heartbroken. It was hard to go to school, watching my ex-BFF act as if nothing were wrong, as if the world was perfect when, to me, it had fallen clean off its axis and rolled right over my heart. I’d come home crying, hide in my room, ignore all the books that I’d never have the chance to lend. I hated school. I hated people. I hated life.

You know how it is.

In the throes of my despair, Omma told me a story:

I had a best friend too, Sun Young, when I was your age. Just like you and Sally, she and I would trade stickers, stay after school to help the teacher wash the chalkboard, braid each other’s hair. And then one day, everything changed and she stopped being my friend. She gave me the silent treatment and wouldn’t talk to me anymore. I asked her what I did wrong, but she wouldn’t tell me.

According to Omma, though, it didn’t end with silent treatment. Omma’s former BFF got her entire “crew” to start bullying Sunny, snickering at her behind her back, pulling on her braids when standing behind her, calling her names outside of class. After subjecting Sunny to endless harassment for several days, her once best friend and her little girl gang followed her into the woods on her walk home. Sunny was alone. Meanwhile, five girls clad in crisp identical school uniforms, thick black braids, and knee socks, formed a loose ring around her. One by one, the girls crept closer to her, pulling at her hair, tugging at her shirt, jostling her with their shoulders and elbows.

“What did you do,” I asked?

I grabbed each of them — all five of these girls — by the hair. We had long hair back then, because we were not allowed to cut our hair short, like you do now. I grabbed all their hair, and I tied them all into one giant knot!! And they couldn’t move! They were trapped right there, in the middle of woods!

And I ask them, “Why? Why are you doing this to me? What did I do to you?

“Why do you hate me so much? Answer me! What did I do to make you hate me so much?”

Finally, the ringleader, the girl Sunny had spent countless hours with doing all the things that little girls do with their best friends — unable to lift her head or untangle herself from the manes of her recruits— muttered,

“You breathed on my face one day at school.”

Sunny meets her fairy godmother.

As expected, Sunny did very well in nursing school and became a registered nurse in Korea. And sure enough, as her teacher predicted, she was given the opportunity to try for a visa to the United States, where there was a shortage of nurses. I’ve told this story many times before and many of you have already read or heard it, so I won’t repeat it with the same level of detail that I usually do. That said, it is such a critical fork in the road on my mother’s path, so I will go over the highlights.

After two years of working in Korea, Sunny saved $800 before she hopped on a plane to Chicago. She signed a month-to-month lease on a studio apartment right on Lake Shore Drive for $99 a month. Her goal? Pass the U.S. nursing boards so she could get a job at a local hospital and procure a visa that would allow her to stay. The hurdle? Her English. Despite impressing Miss Young with her “My name is Sally!” the nursing exams were an entirely different obstacle–one that she ultimately failed to pass. The morning the exam results were published, Sunny called home and told her dad, “Daddy, I failed.”

My grandfather, of course, said all the things that fathers are supposed to say: “You’re not a failure.” “Of course you can come back home.” And “We love you no matter what.”

But then he also said:

“But if you come home now, Sunny, you might regret it for the rest of your life.”

Sunny headed to the lakefront path to watch “the Lake.” It was her go-to activity when she was feeling blue, and on that day, she felt the inky blue water as if inside her bones. She tried to swallow her father’s words, but they were like trying to swallow the entirety of Lake Michigan. How could she afford to stick around for another round of exams? And how could she learn English well enough to pass them, even if she found the money? Her reverie would soon be interrupted by an old vagrant–a tallish woman with grey hair, pale skin, and bright blue eyes.

“Ma’am, do you have some change for a cup of coffee? It’s so cold,” she said, as she placed her bare hands beneath Sunny’s nose.

Sunny did have some spare change in her pockets, but now was not the time to part with it. Now was the time to scrimp and save every penny she could. But, instead of listening to that sensible voice inside her head, she reached into her pocket, pulled out all the spare change, and poured it right into the old woman’s hands.

As the very last dime dropped with a “clink,” the old woman grabbed for Sunny’s hand before she could pull it back. And she said something that Sunny would remember for the rest of her life, something she would one day repeat to her American daughter:

“You’re going to pass that test.”

Sunny did pass the test. She got a job as a nurse at Cook County hospital, the start of a 40+ years career in the United States. She ultimately worked her way up to become the Director of the Emergency Department of Swedish Covenant Hospital. When she retired, they threw her a party with a huge sheet cake. Despite how much I hated all of them for making my mother work at night, calling her on her days off, taking my Omma away from me when I wanted to spend every waking hour with her, I cried a little to see how beloved Sunny was at work.

“This time, I’m not going back.”

In July 2012, while at a dinner with my family at Shanghai Terrace, I made the mistake of interrupting my husband while he was speaking. That night, at around 2 in the morning, over shards of broken glass, still tinctured with tequila, I ran barefoot out the door of our townhouse, my dog Daisy in my arms. I can still hear her heartbeat fluttering against my own as his fingers grazed my arm, nearly pulling me back into our home, as my feet slapped against the pavement that led directly to my parents’ house, where the door would always open for me, no matter the hour.

Amber light flooded her doorstep as Omma swung the door open. She looked down at me, looked down at my dog Daisy. She didn’t say, “”또?”

But, I answered her anyway.

“This time, I’m not going back.”

Omma paused for a second. Then another. And then:

“Good. Because he ever shows his face here again, I’m going to beat the shit out of him.”

“Don’t you have any faith in me?”

As Omma continues to extol the virtues of a steady paycheck, rattles off all the reasons why leaving the Firm is a bad, bad, bad idea, describes how easy it would be for me to do both–The Korean Vegan and full time partner at a law firm–since, after all, I’ve done it so well all these years, I lean my head back against the wall. Finally, I manage to cut in:

“Omma, don’t you want me to be happy? Don’t you think I deserve to be happy?”

Pause.

“I guess…” she falters. “Yes. Of course I want you to be happy.”

Followed up with,

“But, I’m just worried about you.”

I thought I’d be prepared for this. Maybe I am prepared, or overly prepared. In the previous three years, I’ve learned more about my mother’s story than I’d known in the first 39 years of my life. I know that she nearly died from starvation more times than I can count. I know that she watched her mother almost die from miscarriage and the lack of adequate healthcare. I know that too many times, the uncertainties of life didn’t just cause her anxiety, but nearly caused her death. I keep telling myself that my compassion for my mother outweighs all other things, that I can be firm but understanding. Still, it hurts me to ask my mother,

“Omma, don’t you have any faith in me at all? Your daughter?”

Silence.

I am surprised to find tears welling up in the corners of my eyes.

I think about Mr. Park, the homeroom teacher who refused to let my mother skip high school for the underwear shop. I think about Miss Oh, the English teacher that encouraged Sunny to go to nursing school. I think about my grandfather, the one who told his favorite daughter, “don’t come home because I believe in you even if you don’t.” I think about the old woman on the lakefront path and wonder whether I should head out for a run right that second to see if she might still be willing to exchange my destiny for a cup of coffee. But just as I’m thinking that I should hang up, Omma says,

“Yes. I have faith in you.”

And I realize, then, that Omma may have been thinking of all them, too. That maybe, for a just a second, she was standing on the lakefront path with me, watching the back of an old homeless woman shrinking into the cold.

Ask Joanne

“I just had yet another fight with my parents over what I think is their judgment that I’m not living the life a 30 year old should be living, layers of differences in culture and values, and a complete lack of ability to communicate and be vulnerable with each other. They think the battle is still to survive financially while I’m trying for enrichment and fulfillment spiritually. What advice do you have for first or second generation immigrants who are struggling to be understood by/accepted by/draw boundaries with their parents?” – Jia.

Dear Jia,

Enrichment and spiritual fulfillment are indeed critical to joy and therefore worthy endeavors. I think your parents would actually agree with that, regardless of which generation or country they are from. The problem is, they don’t think either is possible without financial security and, perhaps, the “prestige factor” that often adheres to monetary wealth. They’re not entirely wrong. Ask anyone who has suffered real poverty, true deprivation and they will tell you that any kind of fulfillment and joy is scarce when you are bereft of the basics: food, water, shelter. If joy is the finish line, financial security is the ground beneath your feet. Is it possible that your parents suffered through trauma related to the lack of food, water, and shelter? Even if they didn’t personally suffer from starvation, perhaps they saw others who did? For many immigrants, the life you and I live today is far past what they would have deemed “luxurious.” However, it isn’t possible for them simply to erase the earlier chapters of their lives, the ones filled with abject need–the kind that you and I have likely never experienced.

I say all these things not merely to elicit empathy or compassion, but to be strategic. You’re never going to win over a jury if you don’t get into their minds. Remember, your parents are not just mom and dad–they are also humans, saddled with imposter syndrome, anxiety, and, in many cases, unthinkable trauma. How would you treat someone who wasn’t your mom and dad knowing this about them? You are, in many ways, their most important experiment and, for better or worse, how you “turn out” is a reflection of them. Remember, too, your compassion can serve as a powerful shield, one that will soften some of the criticism your parents will likely try to employ in order to assuage what is, at bottom, their own anxiety.

If you want your parents to understand and accept you, the best advice I can give you is to try, first, to understand them and accept them. Not as some Christian “turn the other cheek” stuff, but to facilitate effective communication. If you try to talk to them like you would talk to your friends, colleagues, partner, or the guy sitting next to you on the bus, it probably isn’t going to work, because let’s face it–immigrant parents are not like all the other people in your life. Specifically,

- Validate their anxieties. Tell them, truthfully and compassionately, that you understand their fears. Full stop.

- Let them talk. As much as they want and need to, just like you would hear out a person who needs to vent, acknowledging them along the way.

- Ask them for help in your journey. Parents are wired to listen for a cry of help from their children. Come to the conversation with concrete things they can do to help you in your path towards fulfillment.

- Be prepared to walk away from the conversation with nothing resolved. Forcing things between you and your parents can cause damage that will continue to hurt everyone down the line.

That last piece–being prepared to walk away–is, in some ways, the most important. When I was a baby lawyer, I would often make the mistake of asking that “final question” during a cross examination just like they do in Law & Order: “You forged that document, didn’t you?” or “You committed fraud and you knew it, didn’t you?” But, those are the easiest questions for witnesses to answer: “Nope! And here, let me tell you all the reasons you are wrong!” At which point the witness spends 5 straight minutes telling your jury why you are a total idiot that no one should trust. As I grew into my practice, I learned the importance of trusting in my jury or judge to make the leap I’d set up for them. Sometimes, Jia, your biggest power play is trusting that the seeds you plant with your parents today, will germinate and grow into a new kind of understanding tomorrow.

Finally, in some unfortunate situations, the good of having your parents in your life can fail to outweigh the bad. As you allude to, boundaries become all too necessary to guard your own mental health. And… your parents might not be too happy with your attempt to install them. In fact, they might take an “all or nothing” approach: if you want our love, you need to take our criticism too. My hope is that your parents love you enough to respect whatever boundaries you think are necessary (e.g., “when we see or talk to each other, we can no longer talk about my career”), but if they don’t, find someone else in your life–a friend, mentor, grandparent, aunt, etc.–who can help fill that void while you grieve and recover from that loss.

Always remember, though, that however much they want to walk this path for you, Jia, your feet, your legs, your heart will carry you to your destination and therefore, above all things, those must be protected.

Updates/Random Things.

- Last week, we went to Toronto to visit the pop-up art exhibit launch party by Han Voice, a Canadian non-profit dedicated to the liberation of North Korean refugees. The staff made the japchae recipe out of my cookbook and I got to meet so many cool people, including Sam, a recent defector from North Korea. You can see and hear more about Sam and the art exhibit here.

- I’ve finally managed to get into a groove here in our new home and you know what that means: lots more recipes! I added a bunch more new recipes to The Korean Vegan Meal Planner, including Fried Rice Spring Rolls, Scrambled “Egg” and Giardiniera Toast, Yaki Udon Salad, and more!

- Corey Booker, a senator out of New Jersey, challenged his Instagram followers to join him in a “no added sugar” challenge between July 5 and Labor Day. Coincidentally, July 5 happened to be Day 1 of marathon training for the New York City Marathon (which I am registered for). So, I thought, “why not?” Sadly, that means no baked desserts from The Korean Vegan for the entire summer (I generally do not like baking with sugar subs). BUT… I just picked up a mountain of fresh fruit from my local farmer’s market and will be making the BEST fruit salad EVER this week. So, keep your eyes peeled for that!

- I saw that Ron Howard is coming out with a docudrama on the Tham Luang Cave Rescue (the Thai soccer team that was stuck in a cave). Before you watch that, though, might I recommend the actual documentary on the story, called The Rescue. Hands down, it was one of the best movies I’ve watched all year. I made my mom and dad watch it with me and they were absolutely astounded. The way the movie makers seamlessly spliced real footage together with re-enactments to tell the tale of this mind-blowing rescue was so well crafted and powerful, I was literally on the edge of my seat almost the entire movie.

- Summer is in full swing and any time the temperature goes above 78° F, I start craving two things: naengmyeon and bingsoo. Naengmyeon is a cold noodle dish that really hits the spot this time of year. Bingsoo is a shaved ice dessert which, as the name suggests, is composed mostly of ice that is often mixed with condensed milk to create a soft “snow.” I developed a recipe using Whole Foods’ non-dairy ice cream and their coconut condensed milk and I SWEAR it was one of the best desserts I’ve ever made. This will likely be the last dessert recipe you see from me in awhile, so check it out!!

Parting Thoughts.

Tomorrow is my mother’s birthday. This newsletter is meant to celebrate her. I know what you’re thinking–how is something that is so “critical” of her a celebration of her? I wanted to write a truthful portrait of not just my mom, but the woman she was and is outside of my mom–Sunny. Or Sun Bee (her Korean name). I wanted to reveal all the parts of her that may have gone ignored when she became a wife and mother and acknowledge that it was partly this negligence that made her regret on occasion, in an all too human way, getting married and having kids. Sunny deserves as much validation and affirmation as does Omma.

All too often, we forget that the people around us are 360° of human. They make choices outside of the four corners of our experience with them and yet we are tricked into thinking that we know our colleagues, our friends, our lovers, and thus can fully appreciate them. But the truth is, there’s a universe of unknown in everyone, even those we’ve spent our entire lives knowing–our parents. Even those we’ve spent their entire lives knowing–our children. When we choose to love someone, by definition, we do not have the option of loving only those parts we know or understand. When we choose to love someone, we cannot allow only those parts we’ve interacted with to breathe. Our parents deserve to be seen as more than our parents. Our children deserve to be seen as more than our children.

And you deserve to be loved for all that you are. Even those parts that will remain unknowable to everyone but you.

– Joanne