Over the past two years, my therapist has set two modest goals for me:

(a) start eating lunch, and

(b) admit you have an eating disorder.

Earlier this year, I came very close to incorporating lunch into my weekday. From Monday through Friday, I run anywhere from 3 to 13 miles, and I furtively toyed with the idea of consuming a small meal around mid-day after some of my longer runs (5+ miles). Sometimes, I would have a protein shake and on other days, I would enjoy a salad. Based upon what my therapist and running coach were telling me, I believed I was doing the right thing for my body and health, as well as propelling my fitness goals.

And then I heard about something called “intermittent fasting.”

All of the sudden, “experts” were questioning the notion of eating lunch. “Why eat lunch? Who says that lunch is a good thing? Who says you should always eat when you’re hungry? What an outdated idea!” In fact, many of these folks were explicit proponents of something that my therapist and running coach consider to be anathema: meal-skipping.

So, after a few weeks of experimenting with lunch-eating, I resumed the old habit of going from breakfast to dinner with no calories. After all, there were plenty of people who claimed to be way smarter than me saying that eating three meals and two small snacks a day was downright silly! Instead of hearing my therapist’s or my coach’s voice encouraging me to “eat some calories!” I heard podcasters and YouTubers and even physicians pushing me to: “Skip lunch! It’s good for you!”

I explained all of this to my therapist, outlining the potential benefits of intermittent fasting. I described to her how her voice had been drowned out by the voices of all those who had studied the power of restrictive eating and she said,

“That’s not an expert’s voice you’re hearing. That’s Ed’s voice.”

“Ed” is the metaphysical incarnation of “eating disorder.” An “eating disorder” is defined as:

any in a group of disorders in which abnormal feeding habits are associated with psychological factors. Characteristics may include a distorted attitude toward eating, handling and hoarding food in unusual ways, loss of bodyweight, nutritional deficiencies, dental erosion, electrolyte imbalances, and denial of extreme thinness. —Medical Dictionary.com

From the minute I walked into her office, my therapist has waged an ongoing battle to get me to admit I have an eating disorder. I have always assumed that it’s her sneaky way of “fattening me up,” as I often joke to her (except I’m sort of only half-joking). And even as I sit here today, I struggle with identifying myself among the ranks of the 30,000,000 people in the United States who suffer from this condition. I’ve never been a fan of pretending to have illnesses I don’t actually have and I’ll be honest: I find it particularly unattractive when people claim to suffer from self-diagnosed “depression” or “OCD” or “ADHD” (all legitimate disorders in and of themselves) or any other convenient “disorder” as an excuse for not getting your shit done.

Mostly, though, I object to applying the term “eating disorder” to me because I’m not skinny.

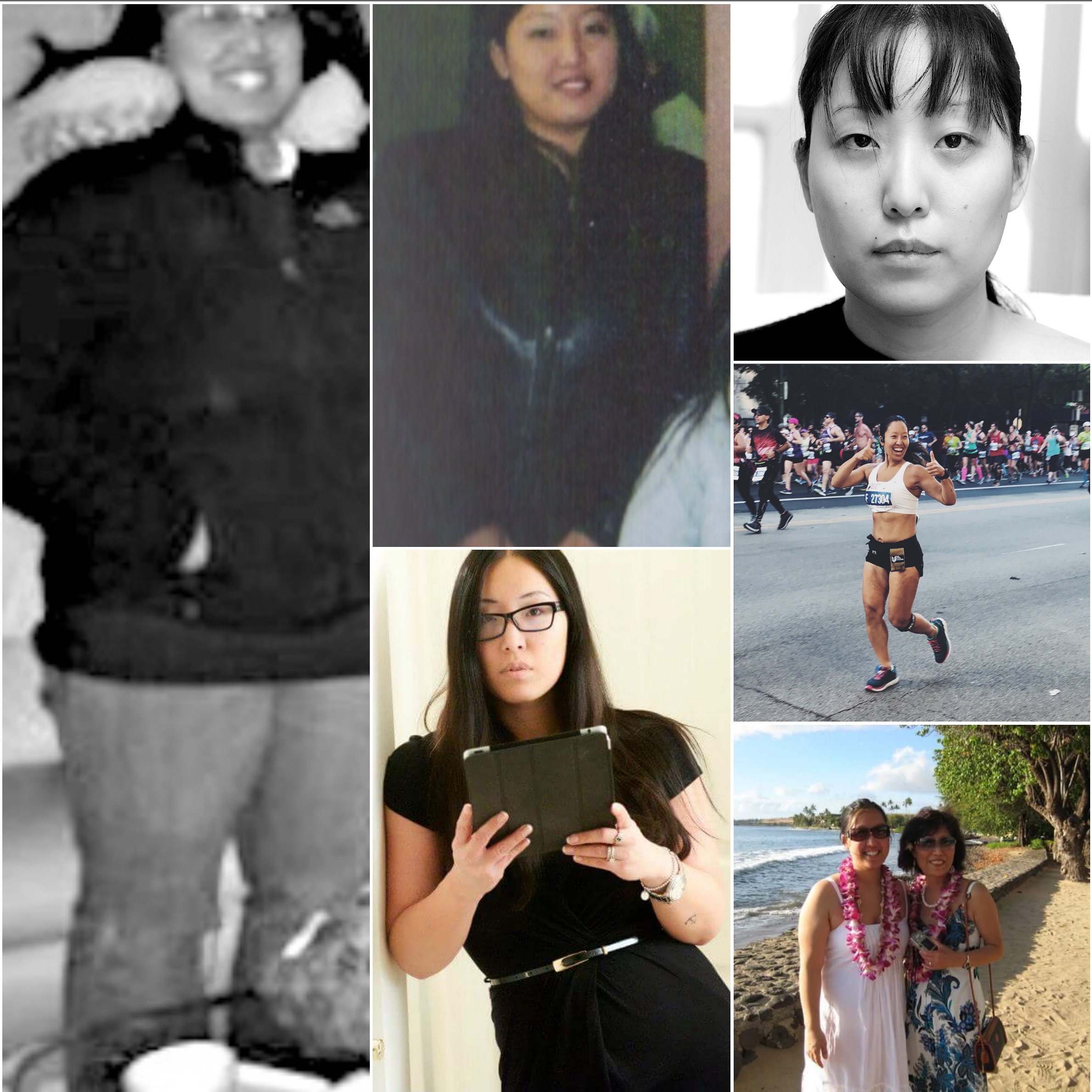

I have never been skinny in my entire life. I have always fallen into one of three categories: (a) chubby, (b) obese, or (c) really obese.

It wasn’t until college that I started obsessing over dieting and losing weight. I gained the Freshman 15 (and then some), and was determined to undo it. I figured the fastest way to erase the excess fat was by eating as little as possible while also spending lots of time on the treadmill. So, I ate one meal a day and exercised 5 times a week. This was the first step on my journey towards becoming a “yo-yo dieter.” While restricting so severely certainly yielded tangible results (my family constantly commented on how “great and pretty” I looked), it made me crave food in a way I hadn’t before. I often went on binges–sometimes for several days–to compensate for how “good” I was being on my diet. I would lose weight, gain it all back and then some, lose all the weight again, and then gain it back with yet a few more pounds. I repeated this cycle at least a dozen times. I went from being 115 lbs as a college freshman to being 190 lbs by the time I was a practicing attorney.

But in all those years, I never looked at myself in the mirror and saw bones jutting out of my face or my ribcage pressed up against my skin–what I believed to be the hallmarks of an eating disorder. No one in my family ever said to me, “Oh Joanne, eat something, you’re too skinny.” So, to me, it didn’t matter that sometimes, I would go for days without eating anything but a handful of chocolates or cookies, or that I would binge on French fries and ice cream in the dark when no one else was home, or that I sometimes forced myself to throw up after I’d been “bad” over the weekend.

It also didn’t matter that I underwent four different plastic surgeries in an attempt to be skinny, or that I weighed myself sometimes 15 times a day. It didn’t matter that I drank laxatives in the morning and at night and that the very last thing I did before bed was review the day’s calories in my food diary.

It certainly didn’t matter that I would often wake up feeling as though I could never be happy because I was fat or that I would routinely break down in my bedroom and sob into my pillows because the scale said the wrong thing. It simply didn’t matter that my life was one never-ending calorie calculation, that I could see the unyielding path of lifetime dieting stretch out before me in one clean straight line all the way to the horizon–a vision that kept me up at night and even made me question the point of living at all on quiet afternoons when no one is at home except for me and my dog.

None of these things mattered.

I didn’t have an eating disorder because I wasn’t skinny.

A good friend of mine is a champion for the body positivity movement–something I initially viewed with the same skepticism as “depression” and “organic food.” She recently posited that it’s much unhealthier to suffer from an obsession with losing weight than it is to carry too much fat. I wasn’t sure I agreed. The cost–both financial and medical–of being overweight were well documented, with over a century’s worth of evidentiary support. Astronomical healthcare costs and the rising death toll from heart disease dwarfed any meaningful statistics on eating disorders. I repeated the assertion to my husband over vegan quesadillas at our favorite Mexican joint: “Do you think there’s some truth to the idea that the cost one incurs to live up to some impossible ideal of beauty is higher than being overweight?” He thought for a moment and said, “You know, there a ton of people who suffer various medical conditions associated with being overweight. Not a lot of people really ‘suffer’ from trying too hard to be perfect. I honestly don’t know anyone who does,” he concluded. But then he tagged on, “Except for you.”

I nodded. Perhaps he was right. I thought of the nameless “skinny” women at the dog park–with their perfect legs and small waists, happily depositing bagels and chocolate donuts down their throats while their dogs pissed all over the water fountain. Or the girlfriend who scarfed down bacon burgers and tacos for dinner on the regular with complete impunity, while still maintaining a size 0. Or my own mom–eating white rice and cream puffs and cookies while never weighing a pound over 90 in her entire life. And then there are those who blissfully don’t give a fuck that their thighs swish or that their favorite pair of jeans from college would never be worn again or that they couldn’t run a mile without stopping. Surely, none of these women agonized over “calories in v. calories out,” had their weeks ruined over one bad selfie, or wept pathetically while kimchi-squatting over the scale for the 27th time in one day. No, no, I reasoned. That unique variety of suffering was reserved for a fraction of a fraction of humanity and therefore, my husband was right–the health risks of obesity outweighed any collective suffering caused by disordered eating.

That night, at three in the morning, I woke up and could not fall back asleep. I stepped out of our bedroom into the pitch black living room, tiptoed over to the couch, and stretched out with phone in hand. I scrolled through the feeds of all of my social media. I went back through some articles I’d saved for later and decided that 3:03 a.m. was as good a time to read them as ever. “Everything You Know About Obesity Is Wrong” surfaced provocatively to the top of my feed and I tapped.

To be honest, despite the overt “clickbaitiness” of the byline, I had skipped over it during breakfast the day before (when I typically catch up on the news) because I didn’t enjoy being told I knew nothing about obesity. After being obese for half my life, seeing a therapist to work on my “food issues,” and reading thousands of pages of books, blogs, and peer-reviewed medical studies on “fat,” I knew a shit-ton about obesity and didn’t appreciate someone presuming that I didn’t.

But instead of disagreeing with everything in the article, I found myself nodding my head. This was not an article attempting to persaude its readers that obesity wasn’t linked with myriad of fatal diseases. Its point was something entirely different:

The emotional costs are incalculable. I have never written a story where so many of my sources cried during interviews, where they double- and triple-checked that I would not reveal their names, where they shook with anger describing their interactions with doctors and strangers and their own families. One remembered kids singing ‘Baby Beluga’ as she boarded the school bus, another said she has tried diets so extreme she has passed out and yet another described the elaborate measures he takes to keep his spouse from seeing him naked in the light. A medical technician I’ll call Sam (he asked me to change his name so his wife wouldn’t find out he spoke to me) said that one glimpse of himself in a mirror can destroy his mood for days. ‘I have this sense I’m fat and I shouldn’t be,’ he says. ‘It feels like the worst kind of weakness.’”

Abruptly, a grapefruit lodged itself in my throat and tears started fanning down my face. “One glimpse of himself in a mirror can destroy his mood for days” was an articulation of a phenomenon I knew all too well but could never say out loud. It was why I hated taking showers, often undressed in the dark, or punished myself by wearing the same dirty clothes for days–because I didn’t want to look at myself in the mirror or find out an old outfit no longer fit comfortably, for fear it would crater my mood.

On the very last night of my honeymoon in Italy, my newly-minted husband took a photo of me with his phone during pre-dinner drinks. I was wearing a white t-shirt and a frilly white skirt I’d picked up at a small boutique in Rome. In my head, I thought I looked nice. But in the phone-pic, I didn’t see a blushing bride or newlywed. I saw the same “man shoulders” I could never shed, the “chipmunk cheeks” I had spent $2,000 to surgically remove, the back fat I tried to starve out of existence in the weeks leading up to my wedding–in other words, the same dumpy girl I could never outrun, despite all the thousands of miles logged onto my calorie calculator. By evening’s end, I was convinced that my husband of 10 days was disgusted with my appearance and ashamed of me. It was impossible for him to look at me without regret, I concluded, over the grotesque body he was required to “love.” And I did what any other rational person in my shoes would do: I picked a fight. Long story short, we spent the last day of our honeymoon bickering or shrouded in a stoney silence as cold and grey as the Pantheon across the square from our honeymoon suite.

To me, I had tens of thousands of photos like this one stored on my phone and other various digital devices that proved, indisputably, that I was not skinny, not starving myself, and therefore, not suffering from an eating disorder.

It seems I am not alone in believing that eating disorders are reserved for the skinny. The article profiled a woman named “Enneking,” who’s story sounded too familiar:

Despite six months of starvation, she was still wearing plus sizes, still couldn’t shop at J. Crew, still got unsolicited diet advice from colleagues and customers. Enneking told the doctor that she used to be larger, that she’d lost some weight the same way she had lost it three or four times before—seeing how far she could get through the day without eating, trading solids for liquids, food for sleep. She was hungry all the time, but she was learning to like it. When she did eat, she got panic attacks. Her boss was starting to notice her erratic behavior. ‘Well, whatever you’re doing now,’ the doctor said, ‘it’s working.'”

I thought of all the times loved ones dismissed my struggle with food or assumed I was eating enough simply because, “You’re not that skinny.” There, in my living room at 3:14 in the morning, swaddled in a throw and the unique solemnity of insomnia, as I read one story after another that hit too close for comfort, I imagined all the nameless men and women who curled up into a ball in their beds or wrapped their arms around their naked knees in a “shower-in-the-dark” or averted their gaze from the dozens of accusatory mirrors in the gym locker room or woke up every day bearing the weight of a stone on their right shoulder–a stone permanently lodged there to remind them of one inexorable truth:

You will never ever be happy because you will always forever be fat.”

I cried. For me. For us. For our self-imposed isolation. For our inability to come clean with each other and to hell with our fucking shame. For that “emotional cost” I had been so quick to write off as trivial, in a breathtaking denial of a pain I knew as well as the face I hated seeing in the mirror.

In the past year, I have run three marathons. In 3 days, I’ll be running my fourth at Indianapolis. Since October 2017, I have run over 1,545 miles. I have often suggested to my social media followers and my therapist that running has been my salvation–that it is the only thing that allows me to set goals (i.e., run faster) unrelated to the way I look, and that meeting those goals requires a steady stream of calories.

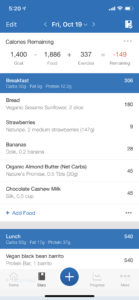

About 10 days ago, in anticipation of a 20-mile run–my last significant run before tapering for the marathon–I consumed 1886 calories, an amount that is about 600 calories more than average. I have used a calorie calculator for over a decade. I generally like to keep my “net calories” below 1,000. Seeing my calories “in the red” on my calorie calculator incited intense anxiety, but I reminded myself how shitty things had gone the last time I’d under-eaten before a 20-miler. The next morning, I was still tired after two brutal weeks at work and little sleep. The marathon I had completed just 13 days before still had a grip on my legs and I could sense their fatigue the minute I stepped foot onto the gravel path at Waterfall Glen. By mile 10, I wanted to pull over and lie down on the park bench or sprawl out on the cool dirt of the forest. At mile 15, my coach pulled up next to me on his bike and sensing my struggle, suggested I call it a day: “I don’t want you to blow out your legs before Indy.”

I couldn’t look at him. But I didn’t have the energy to lie either:

“You won’t like hearing this. But I can’t stop, because of all the food I ate yesterday. I have to burn all of that off.”

He knew better than to argue with me right then and there, and simply stated, “We’ll tackle this after Indy. For now, I want you to walk every half mile for one minute for the rest of this run.” He offered me some water and an encouraging smile and it was all I could do not to burst into snot-filled tears under the warmth of his compassion. He cycled off back towards the start of the trail and disappeared around a thick copse of gilded trees.

I turned my headphones off and started pumping my legs again, listening for each footfall and envisioning the line they were creating along the path, a line I hoped could pull me along and far away from the questions I could feel nipping at my heels and lashing at my calves.

When will you ever stop counting calories?

When will you ever stop being fat?

When will you ever be happy?

Why can’t you beat this?

Have you ever tried running and crying at the same time? It is neither pleasant nor attractive. My croaking gasps echoed throughout the forest and I worried a fellow runner might burst through the trees looking to put a dying elk out of its misery. However often I pressed the heel of my hand to my face, the tears replenished themselves with an immediacy that was both annoying and alarming. This was no “self pity” cry because I didn’t want to run anymore or because my legs hurt or because I was upset with myself for eating too much. No, I was grieving over the loss of my agency, the bitter irony of ceding all my power in a frantic grasp at control. I cried not because my coach told me to stop running, but because for some inexplicable reason, I could not. I wept for “Baby Beluga” and “Sam, the medical technician” and “Enneking, the plus-sized eating disorder,” and the insidious sadness that infected all of them and me so unobtrusively I had simply taken for granted the fact that I could live the rest of my life knowing I would never be fully happy, because I just wasn’t that skinny.

It was a beautiful morning that day. The sun stroked the wisps of hair around my face and the dappled trees shook as if to acknowledge the ache spreading through my chest. A friendly breeze hurtled through the branches and carried my sobs far away from my lips and wiped from my face any evidence of despair. I wish I could tell you I stopped running, or even that I pulled over and walked every half mile like my coach instructed. But I did neither.

I finished two loops and literally ran into the arms of my waiting husband, who congratulated me on completing my “last long run” before my marathon. I smiled and waggled my two fingers in the obligatory “V for Victory” sign my mother taught me when he insisted on taking a picture of me at the finish. My sweet husband, who consistently praised me for my ability to change, when others couldn’t; who hollered my name unabashedly at every 5k, half-marathon, and marathon I ever ran; who bragged to anyone who would listen about how extraordinary his wife was… I guffawed at all his jokes, chatted noisily during the car-ride home, and planned out all the food we would eat to recover, so as to leave no room for the source of my indescribable shame.

I finished two loops and literally ran into the arms of my waiting husband, who congratulated me on completing my “last long run” before my marathon. I smiled and waggled my two fingers in the obligatory “V for Victory” sign my mother taught me when he insisted on taking a picture of me at the finish. My sweet husband, who consistently praised me for my ability to change, when others couldn’t; who hollered my name unabashedly at every 5k, half-marathon, and marathon I ever ran; who bragged to anyone who would listen about how extraordinary his wife was… I guffawed at all his jokes, chatted noisily during the car-ride home, and planned out all the food we would eat to recover, so as to leave no room for the source of my indescribable shame.

About a week ago, during the middle of a particularly grueling day at the office, I stopped what I was doing and wrote the following in an email to my husband:

Within minutes, he wrote back:

That day, I did two things:

I admitted I have an eating disorder.

And I ate lunch.

In three days, I hope to run the fastest marathon I’ve ever run. Afterwards, I intend to look straight into the mirror and tell the woman looking back at me just how proud of her I am.